It is impossible to imagine Superman being as popular as he is and speaking as deeply to the American character were he not an immigrant and an orphan. Immigration, of course, is the overwhelming fact in American history. Except for the Indians, all Americans have an immediate sense of their origins elsewhere. No nation on Earth has so deeply embedded in its social consciousness the imagery of passage from one social identity to another: the Mayflower of the New England separatists, the slave ships from Africa and the subsequent underground railroads toward freedom in the North, the sailing ships and steamers running shuttles across two oceans in the 19th century, the freedom airlifts in the 20th. Somehow the picture just isn't complete without Superman's rocketship. Like the people of whose values he defends, Superman is an alien. He's the consummate and totally uncompromised alien, an immigrant whose visible difference from the norm is underscored by his decision to wear a costume of bold primary colors so tight as to be his very skin. . . . .

Superman's powers--strength, mobility, x-ray vision and the like--are the comic book equivalents of ethnic characteristics, and they protect and preserve the vitality of the foster community in which he lives in the same way that immigrant ethnicity has sustained American culture linguistically, economically, politically and spiritually. The myth of Superman asserts with total confidence and a childlike innocence the value of the immigrant in American culture. -Gary Engle, from Superman at Fifty! edited by Dennis Dooley and Gary Engle

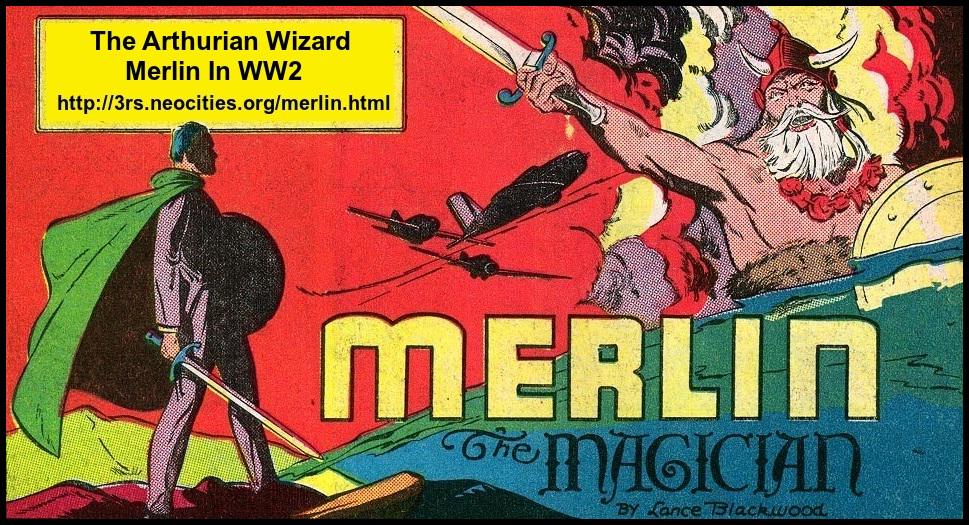

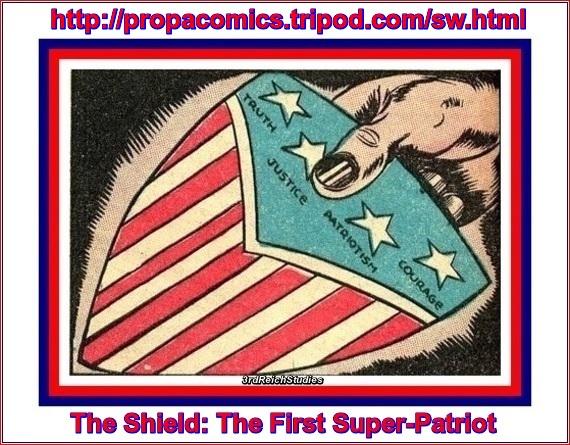

According to most comic book historians, Superman's creation heralded the beginning of the so-called "Golden Age" of comic books, the era during which the visual grammar of the medium was established. It was also a time when many classic characters were created. There was nothing overtly Jewish about the characters created during this era. However, occasionally a comic book character would emerge that had certain Jewish signifiers.

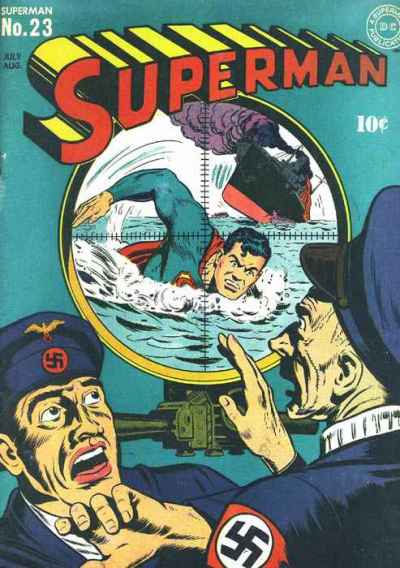

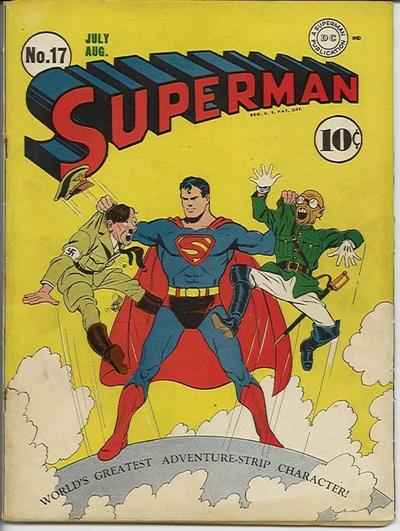

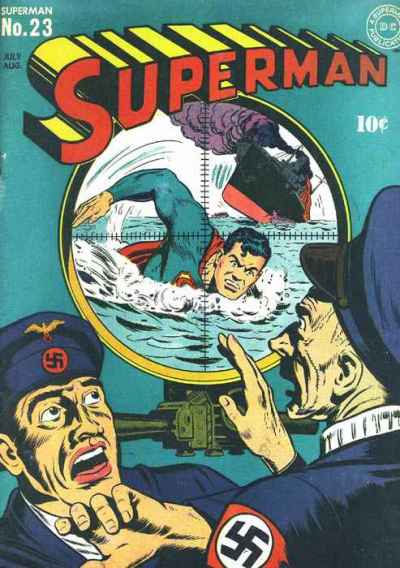

After America became involved in World War Two, Timely Comics superhero Captain America's Jewish creators Joe Simon and Jack Kirby pitted their star-spangled warrior against the Nazi agent Red Skull. Captain America's alter ego Steve Rogers could be seen as a symbol for the way Jews were stereotypically depicted as frail and passive. That is, until he took a serum that transformed him into the robust Captain America. The serum was created by "Professor Reinstein," an obvious nod to famed Jewish physicist Albert Einstein. And Superman gave such a pounding to Nazi agents from 1941-45 that, according to legend, Nazi Minister of Propaganda Joseph Goebbels jumped up in the midst of a Reichstag meeting and denounced the Man of Steel as a Jew. -Arie Kaplan

Contents:

Contents:

Klaus Nordling's: Shot and Shell

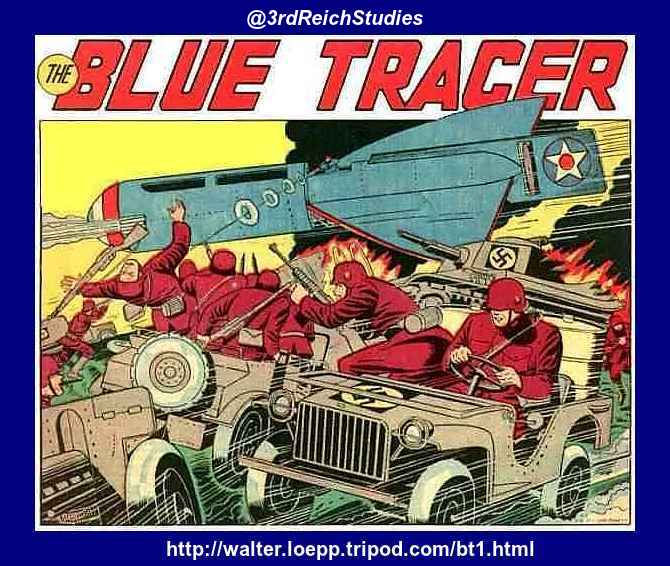

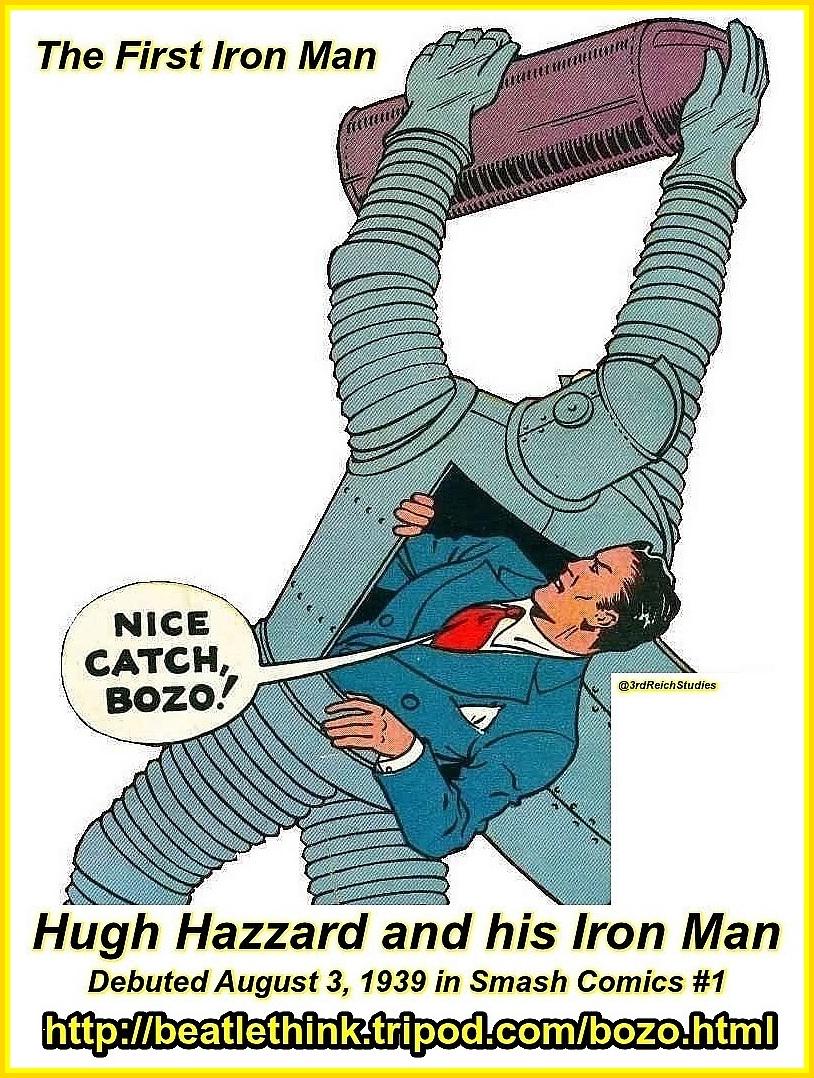

Even with the explosion of superhero films daily radiating from Hollywood, the comic book today is still considered kids stuff. It wasn't always so. Back in 1938, when Hitler was beginning his string of conquests, the first superhero comic book went on sale in the US; Action Comics #1. The creation of two Cleveland teenagers of Jewish descent, the issues lead feature, Superman, was an instant success, and soon many imitators were competing for space on the newsstands. The form was quickly accepted as a cultural phenomenon on a par with motion pictures, radio, newspapers (comic books evolved directly from newspaper comic strips) and magazines (the negative connotations associated with comic books did not emerge fully until many years later).

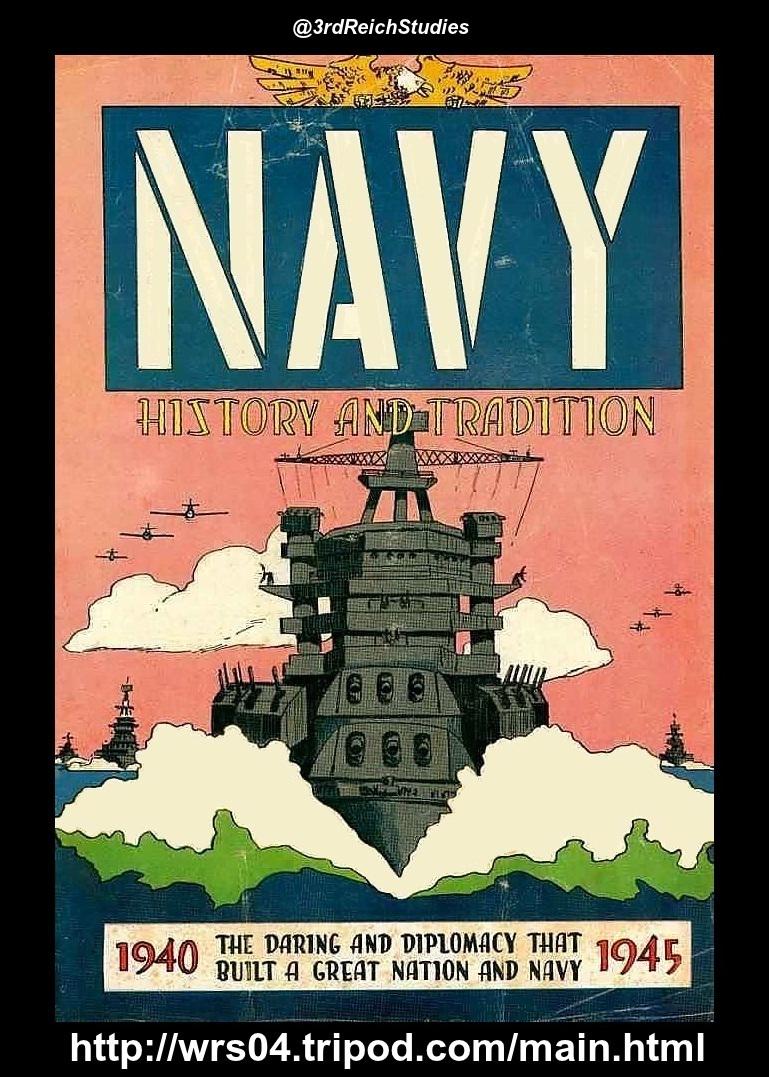

A casual perusal of what passes for a comic book in modern times reveals that the basic form remains consistent; drawn pictures and text sequentially presented to tell a story. That is where the similarities end, however. The two major differences between the comics of today and those of the Golden Age of Comics (roughly 1935-1956) are dollar value (a 1940's comic averaged from 48 to 64 pages for 10 cents; now you get about 21 pages for three-plus dollars) and popularity (1940's comics regularly sold between one half to well over a million copies per issue, with many more actual readers; today, the most popular comics sell a small fraction of that). The significance of these two facts is profound, particularly when one considers that the average age of readers of comics during the Golden Age was much broader than any time since; a typical comic made the rounds of the entire family.

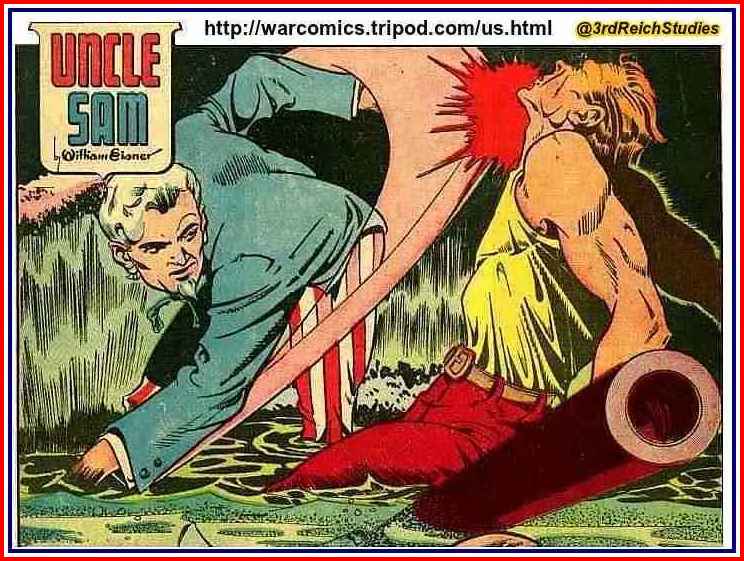

Another striking aspect of the early comic book is the almost exclusively working-class origins of the top creators of the new field, usually represented by the sons of recent immigrants from central and eastern Europe. Perhaps Will Eisner's semi-autobiographical graphic novel 'A Contract With God' portrays a universal experience many of the early comic greats shared to one degree or another? One could make an exception-rich case. What is clearer is that, while one was obliged to bow and scrape to radio and movie producers to see ones intellectual property performed in public, comic creators (pulp writers also, much earlier) were free to manufacture content amenable to their own views and tastes, subject only to the whims of editors (usually of immigrant, working-class origins themselves) and commercial realities (one of which is that they were barely compensated, monetarily).

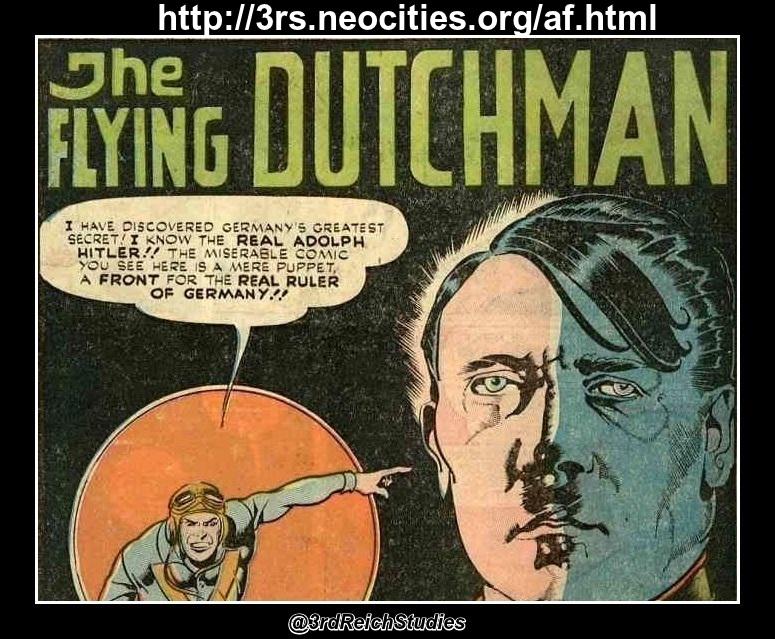

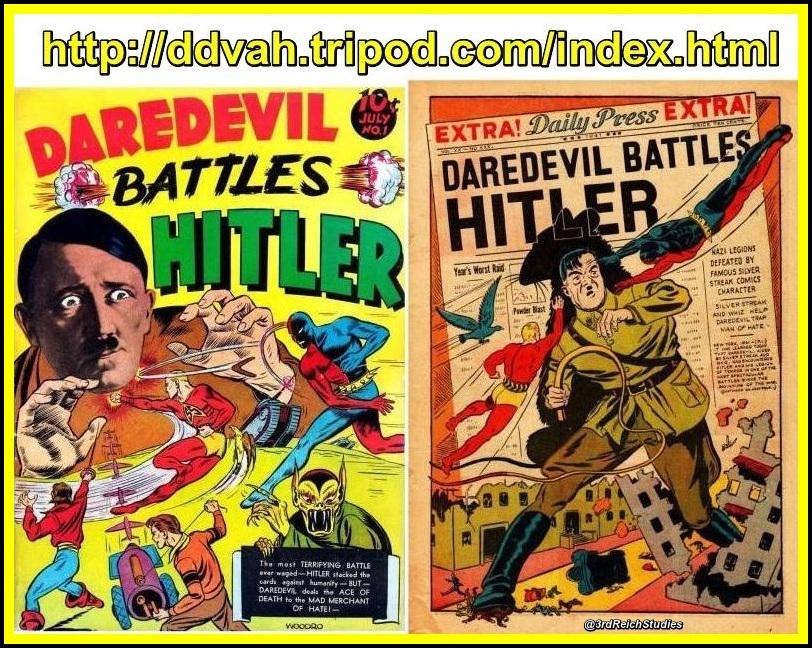

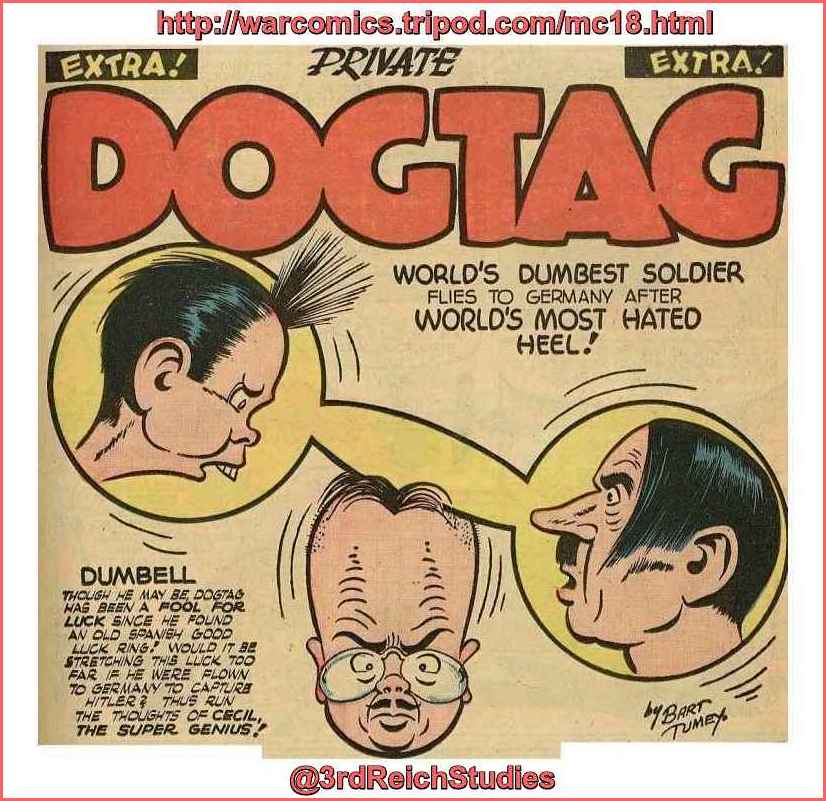

Due to their recent connections to Europe, and their subsequent familiarity with the plight of vast swatches of humanity trapped within Hitler's reach, the early comic creators discussed here were ahead of the curve concerning American involvement in stopping Hitler. These tendencies are starkly revealed by countless comic book stories published before the US entered the war in December of 1941. At first, the 'villain' of the piece in an early comic would be a Hitler look-alike, thinly, if at all, veiled. It wasn't long before that unmistakable mustache was being regularly humiliated and derided in these popular publications, despite the obvious provocation toward another great power that these stories epitomized; imagine a similar circumstance today.

Unfortunately, it has only been in the past few decades that the superhero comic book has been recognized as a unique cultural manifestation of American folk art, and thus worthy of a scholarly approach. Many in-depth interviews of the surviving creators have been conducted by various journalists and fans and published in mags and fanzines over the years; it's difficult to compile this material. The material itself (much of it), once researched, is of variable usefulness, depending on personality, memory, etc. Future cultural historians will no doubt spend decades sorting it all out, but there will be much that is never known due to the tardy perception of worth.

Golden Age comics are notoriously rare due to the all-pervasive wartime scrap paper drives, and only now has so much material from the Golden Age been available for perusal by the non-rich. Sites such as 'Golden Age Comics' (link below) are labors of love perpetuated by heroic scanners who spend countless hours making these cultural treasures freely accessible on the internet (if you're able, you might want to go there and donate something).

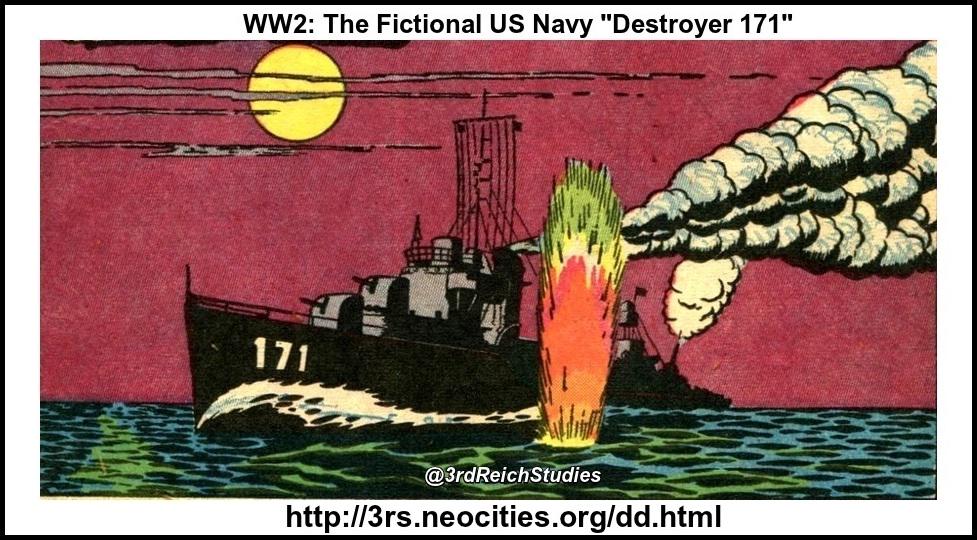

This project is not an excuse to read funny books (though I've been enjoying the break from the much more morose subjects usually associated with Hitler Studies), but a serious examination of an aspect of WW2 cultural expression heretofore ignored. The stories presented here still only scratch the surface of the mass numbers of comics produced in the Golden Age; many key comics have yet to be scanned, and many of those that are available are of poor quality. Still, this is a pretty fair cross-section of a valuable body of culturally significant art. An unexpected depth and variety of public opinion is reflected in these overlooked, illustrated morality essays, and they may now be looked over to advantage. -Wally O'Lepp, 2008

Contents:

Contents:

Twitter: @3rdReichStudies