|

After having solidified his rule in Macedonia and Greece, in the early spring of 334 BC Alexander at last set out from Pella

at the head of his expeditionary force and marched for the Dardanelles. His specific goals in Asia were several. Officially

he was leading a Panhellenic invasion of the Persian Empire to rid the world of tyranny and oppression, and he also sought

revenge on the Persians for their invasion of Greece in 490 BC. He brought his host the 300 miles to Sestos in 20 days. The

advance corps had held the bridgehead and his crossing took place without opposition. He and his party crossed the Dardanelles

in 60 vessels that one of his commanders, Parmenio, had sent down from Sestos.

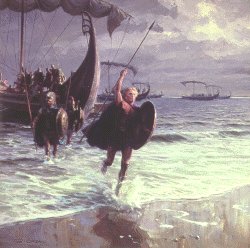

When he crossed the Hellespont with his

army in 334 BC, Alexander threw his spear from his ship to the coast and it stuck in the ground. He stepped onto the shore.

Pulled his weapon from the soil, and declared that the whole of Asia would be won by the spear.

Alexander moved north and rejoined his main army at Arisbe, a little

way out of Abydos. He continued to march north and with only a month's supplies, Alexanders one hope was to tempt the Persians

into a set battle and inflict a crushing defeat on them. He did not have the time or supplies to siege cities along his route

which refused to pledge him allegiance; he had to engage the Persian army soon.

Arsites, the satrap of Hellespontine Phrygia,

sent out an appeal for help to his fellow governors in Asia Minor: Arsamenes, on the Cilican seaboard, and Spithridates, who

ruled over Lydia and Ionia. The three of them set up a camp at Zeleia, east of the river Granicus and summoned their commanders

to a war council.

The Greek mercenary, Memnon of Rhodes, had the best plan. He suggested that they adopt a scorched earth

policy, burning everything before Alexanders advance which would force the Macedonians to withdraw for lack of provisions.

At the same time the Persian should take a large navy and army and carry the war across to Macedonia while Alexanders forces

were still divided. He also advised them that it would be disastrous to fight a pitched battle since the Macedonian infantry

was so superior to their own. This last suggestion so injured the Persians dignity that they decided to ignore Memnons plan

and to fight it out then and there. Also, they distrusted Memnon since he was a Greek mercenary in the service of Persia.

Alexander couldnt have been more pleased.

The Persian cavalry had already reached the river Granicus before Alexander

could cross it and installed themselves on the higher side of the riverbanks while waiting for its slower phalanx to reinforce

them. Alexander sent out scouts who found several places where the river could be forged. His light cavalry and infantry landed

at a place with lower riverbanks and were immediately attacked by the light Persian cavalry. He let the Persian light cavalry

to his troops who had first crossed the Granicus and attacked the Persian heavy cavalry himself.

Persian infantry man

Macedonian hoplite

Persian calvary

The satrap, Spithridates, was killed in this battle. The Persian formation broke and suddenly every Persian was running for

his life. The Greek mercenaries fighting for the Persians withdrew to a small hill where they were surrounded by the Macedonian

phalanx. Alexander refused to accept the surrender of these Greek traitors as he was determined to set an example. When 2000

of them were left, he ended the battle, captured them and sent them back to Macedonia as slaves to work in the mines. Memnon

escaped and eventually ended up on an island in the Aegean where he died of a disease.

After this defeat Darius could

no longer fail to take the Macedonian threat seriously. Alexander had achieved an overwhelming victory at the Battle of Granicus

and the whole of Western Asia Minor lay open before him.

|

|