| « |

October 2013 |

» |

|

| S |

M |

T |

W |

T |

F |

S |

|

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

| 6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

11 |

12 |

| 13 |

14 |

15 |

16 |

17 |

18 |

19 |

| 20 |

21 |

22 |

23 |

24 |

25 |

26 |

| 27 |

28 |

29 |

30 |

31 |

Reflections of the Third Eye

5 October 2013

The mood swings of a movie critic

Now Playing: Pretty Things "SF Sorrow"

Topic: *Books for cineasts

I picked up Robin Wood's Hollywood From Vietnam To Reagan...And Beyond with the idea that it would cast some new light on New Hollywood cinema. It did contain some such, but not as much as I wanted, yet more disconcerting was the generous presence of things I hadn't asked for. Right off the mark Wood comes forward as a really heartfelt feminist, and he tries to enlist the reader on this political agenda by using, among other things, a list of shallow feminist arguments that one usually hears from sincere high school students ("women have never started a war", etc). However, even with a more mature propaganda line, the reader has to wonder what Wood's personal politics have to do with Hollywood movies, and why the reader is supposed to care about them. When Wood then informs the reader that he is gay, British and has a taste for Freud, Sorbonne meta-theory and left-wing politics, one may begin to wonder if the whole persona and text is some sort of superbly ambitious parody, where the unlikely name 'Robin Wood' gives the final clue. But this is probably all real, and once you get past the introduction (I urge you not to read it ) and into the actual essayism, things improve. For a while. The pieces cover a long period, and Wood's most serious critique dates from the 1970s, which is quickly understood even without checking. Presumably damaged by university trends of the day, various movies are scrutinized and analyzed, often intelligently, after which they are forcefed into a mandatory (for 1970s academia, that is) paradigmatic decoding that will, presumably, reveal their dirty little secrets. This paradigm is, of course, either Freudian or Marxist, or when things get really French, Marxist-Freudian. To find out what the film offers in and of its own themes and aesthetics, and what Wood really felt about it, you have to look really hard and maybe it emerges in a side comment. The bulk of the text is taken up by cleverly mapping some innocent screenplay writer's efforts onto Oedipal theory and Das Kapital. Some of it is indeed clever, and the occasional relevance of psychodynamic theories to Hollywood film is obvious since the 1950s. The problematic aspect is when these ideological filters are placed in front of the screen in movies where they simply are irrelevant, and work as obstacles for a useful understanding instead of support. While a psychological reading is often valuable in movies that take the form of character studies or chamber plays, the need for that reading to be squeezed through a predetermined Freudian-Oedipal template is highly debatable; the movie itself, if owing enough depth and consistency, will provide its own psychological ramifications, which should be used as vantage points when trying to extract the sub-text and secondary themes. The need to process any movie through a Marxist decrypting macine is less debatable than absurd, unless the aesthetics at play explicitly refer to that unusual perspective, or if one is writing for a communist publication. Robin Wood was far from alone in this peculiar habit, which is both selflimiting and arrogant (a rare mix) but obviously highly dated. Indeed, the rapid way this external paradigm-based criticism fell out of favor is ironic in view of the haughty undertone that suggests that these readings are the only valid approaches to cinema, now and always. That is not how things turned out, and with psychoanalysis having become more of a checkpoint preceding pharmacological solutions, and with Marxism as a meaningful real-life ideology lying buried in history's great landfill today, one might even feel a certain melancholy when confronted with this programmatic academic criticism from the 1970s and 80s; not because of nostalgia but because of the many good opportunities wasted and the many hours and years spent on this illustrious wild goose chase. At its worst, Wood's book reminds me why I used to hate mainstream movie critics, long ago. But then, lo and behold, the author turns around and delivers a string of essays that are both worthwhile and essentially free from ill-fitting ideologies. Most surprising is perhaps a study of '70s horror and slasher movies which is written in a respectful, almost fan-like tone. And these aren't just any horror movies, but maligned cult works like Texas Chainsaw Massacre, It's Alive, Halloween, Dawn Of The Dead and Last House On The Left. The first and last of these are given long, intelligent and unprejudiced studies which not only praises the directorial skill behind them, but uncovers hidden themes and connections (I'm not sure if it was Wood who first saw how Last House On The Left was simply a remake of Bergman's Virgin Spring, but I suspect it may have been) that are likely to interest slasher fans as much as high-brow cineasts. Clearly written to provoke, these review essays have been vindicated by the passing of time, and Wood's contributions are likely to have assisted in the recognition many of them would receive. Sometimes he may even go overboard--I'm not sure even Psychotronic guys consider Larry Cohen's unusual indie creations to be quite the auteur masterpieces that they are presented as. And then... it's back to Haughtyville again, with an awful, bitter and poorly grounded attack on the blockbuster wave of Hollywood's 1980s. Wood makes it sound like Spielberg and Lucas were out to offend him personally, is blind for the timeless enjoyment and excellent craftsmanship behind the first Indiana Jones movie, and the extraordinary pop culture response to the Star Wars series means nothing to him. Again, I'm reminded of the worst criticism of its day, where aloof Woody Allen admirers would go to see Sylvester Stallone movies and then review them as if they had been presented as Woody Allen films. As mentioned earlier, the New Hollywood coverage wasn't as extensive as I hoped for. Coppola is completely absent (Wood admits, in roundabout terms, that he doesn't understand Coppola's movies), there's nothing about the BBS gang, Ashby, Beatty or Bogdanovich, and the Altman piece is surprisingly negative. What one does get, in this roller coaster ride of a book, is an enthusiastic and generally worthwhile Brian de Palma exegesis, whose main fault is that it was written so early (late '70s). Once more, Wood is surprisingly forgiving of De Palma's known problems (plot holes, strange casting, inconsistent characters) and heaps praise on things like Blow-Out, Dressed To Kill and even The Fury. I would have loved to hear what he had to say about Snake Eyes, for example. Equally enthusiastic and worthwhile are Wood's comments on Michael Cimino's two massive monoliths of controversy, The Deer Hunter and Heaven's Gate. The apologetic tone before The Deer Hunter is surprising given the snide remarks about 'racism' awarded certain other films, but also demonstrates that Wood, when the stars were properly aligned, was able to think outside the box and come up with novel and often controversial perspectives. The Deer Hunter coverage is merely introductory but still manages to make several valuable points, including details that casual viewers may have missed. As controversial, in another way, is the praise laid on Heaven's Gate, whose failure to communicate with the audience Wood explains as a groundbreaking approach to story-telling courtesy of Cimino. That main characters are introduced very late, and that their relations are poorly signalled, and that some scenes go on quite long for no obvious reason, are all taken as part of Cimino's re-invention of cinematic storytelling. Or something like that. I'm not really disagreeing; Heaven's Gate is a fascinating movie, and possibly it may get better the longer cut one sees, but I can't help but thinking that Woods is crediting Cimino with a little more genius than he actually possesses. Another director of that generation to receive a bit of attention is Scorsese, where Raging Bull and King Of Comedy are closely examined, the former for a hidden homosexual theme (which Scorsese apparently agreed on), the latter for a psychological overhaul which occasionally oversteps the line but remains mostly useful and indeed welcome, in view of its undeserved 'minor' status. Wood refers to having covered Alice Doesn't Live Here Anymore and Taxi Driver, but these writings are not included, and given his non-comprehending comments on Taxi Driver (because he dislikes Schrader's male-sacrifice themes), that may be no loss. Schrader gets a dose of Wood's mood swings anyway, as American Gigolo is treated like something that cat dragged in, and rather than a cynical look at a cynical period, its perceived problems seem to be somehow connected to Schrader's personality. Not criticism at its best, or most prescient, given how Gigolo later came to stand as a roadpost where Hollywood's '70s ended and the '80s began. Some modern writings round out the book, but they're vague and bland and look to be there mostly so it could be presented as an "update". In toto, I rarely recommend cherrypicking, but Wood's criticism is so very uneven in quality and tone that it's the best way to approach this collection--I recommend reading the chapters on '70s horror movies, De Palma, Cimino and Scorsese, and much or all of the rest can be ignored with no loss.

Posted by Patrick at Lysergia

at 2:12 AM MEST

Updated: 8 October 2013 8:13 PM MEST

29 September 2013

Cool Hand Luke

Now Playing: Roma-Bologna half-time

Topic: C

I tracked onto an accidental Paul Newman theme with my three latest movie screenings, and why not. For one thing, Newman was one of relatively few who brought a touch of classic Hollywood charisma to the 1960s descent of American cinema. After The Hustler (reviewed below) the time has now come to COOL HAND LUKE (1967), which could be seen as a slightly later chapter in the saga of the same protagonist. The presumably type-cast Newman plays almost identical characters: cocky, independent alpha dogs, gaining admiration for their natural self-assuredness, but also lacking in self-insight, unfit for social games, and prone to drastic, unpremediated action. One gets a sense of a person who could achieve great things, but keeps tripping on his own impatience and egocentricity. This was one hero-type, perhaps the dominant one, for the pre-counterculture 1960s, rooted in the James Dean blue-jean rebel on one hand, and Kerouac’s beat outsider on the other hand. Beyond the main character, and Newman’s performance, the two movies are almost opposites; where the black & white The Hustler is artistic, psychological, dark and urban, Cool Hand Luke is traditional in direction and straightforward in character presentation, set mostly outdoors and shot in brightly lit technicolor. After a minimal prologue, the viewer finds ‘Lucas’ (Newman) arriving at a prison work farm where he’s been sent for 2 years for a seemingly minor offense. Taking it in stride, he tries to play the prison game best he can, being polite to the guards and seeking a place in the convict hierarchy. Lucas’ natural instincts to challenge authority and never give up wins him admiration among the prisoners, whose inofficial leader (George Kennedy in an Oscar-winning role) adopts the ‘new-beat’ and gives him his nick name, ‘Cool Hand Luke’. Things proceed in the dull, cyclical way one expects at a lock-up facility, the only break being the unexpected visit from Luke’s mother, a charmingly eccentric performance by Jo Van Fleet. This short sidetrack is vital not only for narrative purposes, but also because the dialogue offers some needed exposition of Luke’s background; not much but enough to add another dimension to his character. Shortly after this visit the mother passes away, which sets the final act in motion.

"What we have here is a failure to communicate..."

NOTE: the next two paragraphs are crammed with spoilers, and you may want to skip these if you haven’t seen the movie. There are some minor spoilers in the later paragraphs. After being put in isolation for no significant reason, Luke’s attention moves from avoiding boredom into plans on escaping. This he does with remarkable ease (it is a work farm and not a maximum security prison), but after outrunning the guard posse and their trained bloodhounds, he is spotted by a policeman and taken back. Duly punished for his crime he gets back with the chain gang again, only to escape once more. This time he’s away for some time, enough to send a greeting to his convict friends, but ultimately he is turned in and returned to the work farm. Luke is badly beaten by the guards, who with the prison warden’s support decide that his spirit must be broken. This is achieved through a powerful sequence which has an injured Luke being ordered to dig out and fill in a grave-like ditch, over and over, until he finally collapses and begs for no more violence. Seemingly broken, he returns to the sleeping barracks, where his former supporters turn his back on him since he bowed for ‘the man’, no matter that it came after days and hours of torture—a harsh but credible socio-psychological observation. After recuperating, it turns out that Luke was only temporarily broken, and in his most desperate attempt yet, he steals a truck from the guards during roadside work, and is accompanied by George Kennedy’s prison gang leader. The latter celebrates their newfound freedom but it’s clear that Luke was escaping just to escape, and soon gives up. One last provocation from him causes one of the most vicious prison guards to shoot him on sight, after which he’s driven off to the prison hospital, presumably dying. Meanwhile, the convicts are all back in their barracks, where stories of Luke’s actions are already turning into myth. The last scene delivers the image of Luke smiling broadly as the ambulance takes him away. The main theme for Cool Hand Luke is established early on, as the protagonist talks dismissively of all the ‘rules and regulations and laws’ that are in effect in prison, and society at large. Luke is not a professional rebel, but a strong-minded invididual who doesn’t mind restrictions as long as they have nothing to do with him, but who will challenge restrictions that hamper his established freedom. Set at a work farm, the rules and regulations are naturally many, both among guards and convicts. A decorated ex-soldier, Luke is prepared to play the local rules under ordinary circumstances, but with the vicious personalities of the guards, and the subhuman standing of the prisoners, he is no longer in any ordinary environment. Such an unequal system will soon turn out to be flawed and begin breaking its own rules, after which an independent soul like Luke can no longer accept it. This takes place after the death of his mother, when Luke is put in the isolation ‘box’, ostensibly because her death might increase his risk of escaping, but probably because he broke the social protocol of fearful obedience to the most terrifying of the guards, the ‘Man With No Eyes’ (so called because of his reflecting sunglasses). We can see Luke shoot an accusing look towards the guard when he enters the box. After getting out, he immediately sets about escaping, which he had shown no inclination towards earlier. The significance of the change is clear: the prison system violated its contract with the prisoners by putting him in isolation for no valid reason, and so he is not obliged to maintain his part of the contract, i e: not try to escape. His subsequent escapes are not so much yearnings to be free as protests against a prison which fails to follow its own code, while handing out extremely limiting regulations to the prisoners. This becomes clear towards the end, where Luke finally manages to prove, at a sufficient scale, that the laws and rules of imprisonment are just a shell under which people, some worse than others, act out primitive games of oppression. The final two images reveal this theme in a precise, memorable way: the seemingly unbreakable glasses of The Man With No Eyes lying broken on the ground, and Luke’s smile as he’s taken away. Earlier on in the movie we have seen the complete opposite of the corrupt prison system, in the drawn-out boxing match between Luke and the prison gang leader. True to his character, Luke refuses to give up and stay down, despite being knocked to the ground over and over, and ultimately the other convicts find his helpless resistance painful to watch. The gang leader too realizes that the rebellious heart of Luke won’t give up until he is beaten to death, and abandons the fight, after which Luke is accepted into the social circle of prisoners, where he soon becomes a favorite. In other words, George Kennedy’s gang leader refuses to follow the rules of the game (boxing) and knock Luke down until he can’t get up anymore, because he respects Luke’s will-power and fears the outcome. In this scene, the law is shown to be flawed and is ignored by a player for humane reasons, whereas in several other scenes with the prison guards, the law is ignored by players for inhumane reasons. This in turn demonstrates what I assume to be the main point of the movie, which is that rules are theoretical constructions that are never stronger than the people who maintain them. Sometimes the rules are broken for vicious reasons, sometimes for good-hearted reasons. Any person in a regulated system, such as society in general, will have his ideology and will-power tested against the regulations, and in that confrontation a certain number of people will react in an unprescribed way. The admirable logic of Cool Hand Luke is to let these questions and themes be raised among people who are locked in at the fringe of the general system. However, rulebreaking in this local fringe system (a prison) will usually lead to two completely different outcomes, proving in yet another way how imprecise and situation-bound the codes and rules are. If you are a prison guard, you will probably get away with breaking the rules. If you are a prisoner, you will not get away with breaking the rules, instead you will be punished harder. At the end of the movie, Luke shows us a guard who breaks the rules and for once is unable to get away with it. The Man With No Eyes’ first punishment is instantaneous, as the prison gang leader attacks him violently. The second punishment is symbolic, as the reflecting sunglasses are trampled down and run over by a police car (representing the general system). The third punishment is predicated by the law of the general system, which will bear down on a prison guard shooting an unarmed escapee for no reason. The vital achievement that causes Luke to smile at the end is not provoking the shot, but forcing the local system into openly revealing its broken, inhumane nature. A second thematic cluster deals with the communication and handling of rule violations in a given system or game. The presence of this theme is shown by the prison warden’s sarcastic line ‘failure to communicate’, which Luke repeats at the end of the movie; it is in fact his very last line. The movie raises the question of how that failure manifests itself in a local prison system in comparison to the general society system. A prisoner complaining of mis-treatment (rule-breaking) will probably be punished if he makes his complaint inside the local system. Outside the local system, in communication with a lawyer or relatives, his complaint may be received, but it will not carry much weight due to the low status of an inmate. This structure can be applied to many instances of delimited human systems, with different results. If a factory worker discovers that his employer is accidentally poisoning the local river due to cost cutting, the result of his communication will be radically different if he goes to his superiors, to the proper government branch, or to an environmental organisation. Cool Hand Luke does not explore this secondary theme to any great extent (many other movies do; Michael Mann’s Insider is an example) but it is a testament to its strongly articulated script that it opens a useful door to such a discussion. It’s easy to take Cool Hand Luke as an above-average contribution to cinema’s long line of prison movies. The loud extroversion and presence of the main characters, the recurring violence, the menacing guards and improvised social structure among the convicts are all typical elements. But it isn’t quite a prison movie; the escape plans that usually are central to the narrative are completely absent until Luke comes out of the isolation box, and the escapes themselves are simple and unglamorized—we don’t even get to see what Luke does when he stays free for a relatively long period after the second run. Nor is there the typical internal strife between different groups of convicts, on the contrary is this one big happy family after Luke has been absorbed by their social body. More than a prison movie, Cool Hand Luke is an archetypal drama which is unusually distinct in the way it deals with the themes discussed above. The underlying thematic structure dictates the flow of the storyline, which ensures that the vital points are brought home, while a self-confident intelligence in the script ensures that there is a thankful lack of overstatement or sentimentality (frequent plagues of older Hollywood movies). It is not a masterpiece, but it is a movie that combines straightforward storytelling with an unusual clarity of theme, and achieves a very effective balance between the two. The similarity in theme and storyline to One Flew Over The Cuckoo's Nest is obvious, and it is likely that Donn Pearce's 1965 novel that underlies Luke took some inspiration from Ken Kesey's celebrated 1961 debut. Returning briefly to The Hustler, I believe that a film student will find more to chew on in that movie, both in terms of form and psychological content, than in Cool Hand Luke. As a total experience however, I find the latter to be the slightly superior work, due to its powerful subtext and a hands-on execution which raises very few objections in the viewer (the overly long egg-eating bet is my main complaint), or at least in this viewer. 7 of 10

In 'Spot The Star' one can find Dennis Hopper, Joe Don Baker (young and uncredited), Harry Dean Stanton (already looking old) and Anthony Zerbe (his debut) in small roles as convicts.

Posted by Patrick at Lysergia

at 9:47 PM MEST

Updated: 29 September 2013 10:46 PM MEST

28 September 2013

The Hustler

Now Playing: Electric Prunes "Mass In F Minor"

Topic: H

To those who grew up in the 1980s and 90s, Robert Rossen's THE HUSTLER (1961) is known, if at all, as a distant prequel to Scorsese's The Color Of Money (1986). The relationship between the two movies is interesting but shouldnt obscure the fact that Scorsese's movie is a bit of a drag; a cinematic experience comparable to the cold, damp Midwestern towns where the action is set. The earlier movie is a richer and more engaging way to spend two hours, and indeed its standing among film aficionados deservedly surpasses that of the 'sequel'. Shot in appropriate black and white, The Hustler tells a fairly compact story of a masterful young pool hustler (Paul Newman) who breaks up with his former financier, meets and moves in with a young woman (Piper Laurie), reluctantly takes on a new financier (George C Scott) and finds himself beset by loyalty clashes, guilt and a need for freedom. Hovering over this character study like a white whale is the number one pool player around, Minnesota Fats (Jackie Gleason), who uses his experience to defeat and almost bankrupt the hustler Eddie Felson, in a marathon pool game at the outset of the movie. Felson is haunted by this humiliating loss, flying in the face of his great talent and extrovert arrogance. The Minnesota Fats game is less a subplot than a main theme, thoroughly entwined with the other central theme, relationships, to form a steady backbone.

The strength of the themes helps the movie reduce problems that threaten to arise from an unusual and less than ideal dramatic structure. As mentioned above, the movie starts off, after a thin pre-credit excuse for an exposition, with what is actually its dramatic peak, the 30-hour pool hall challenge between Felson and Minnesota Fats. The sequence is allowed to play out its full potential and is well exploited for tension in both psychology and pool playing, which is all fine and good, but once it's over the spectator may feel like the storyline is about to enter the final act, while the screen so far hasn't shown much beyond an exciting game of 8-ball. For a while it looks like Rossen's bold narrative move is going to work, mainly because of the intriguingly downbeat and urban/modern-style relation struck up between Eddie Felson and Piper Laurie's troubled young lady. But in the second half of the movie, the price paid for that massive early sequence becomes clear. The action turns rhapsodic and seemingly rushed, in contrast to the first half, and since the psychological interplay between the three main characters (Scott's unsympathetic manager/financier is the third) has yet to be sorted out by the script, they are reduced to rhetoric speeches that 'explains' their predicament, rather than taking the time needed to show it through dialogue and action. Laurie' s young lady in particular suffers from this simplification, discarding her earlier hints of a psychological cluster with material enough for a whole separate movie. Balancing the two entwined themes until the end becomes impossible when the movie's structure is so front-heavy, and ultimately the movie-makers are forced to choose between the Minnesota Fats revenge arc and the three-part psychology arc. On the surface both are allowed to run their course, but only the Fats thread with its theme of maturity and revenge is able to resolve itself within the limited screen time that the third act is awarded. The relationship theme is forcibly brought home with simplifications, poorly motivated acts, and the aforementioned monologues intended to clarify the inner nature of both speaker and target. Rather than being ahead of its time, The Hustler here reminds one of some of the clumsier attempts at psychological drama from the 1950s. The viewer can witness Rossen's dramatic engine trying to catch up with its timetable during the last half-hour, as the sequences become shorter and shorter, scenes are compressed to become near incomprehensible, and the whole psychodynamic resolution is thrown against a wall in the hope that something will stick as legible closure. This is a disappointing dramatic failure, probably accentuated in the clipping room, with Piper Laurie's character the main victim. Newman's Felson fares a little better as he is given a parallel chance to reveal his full, matured personality via the Minnesota Fats re-match. George C Scotts character is given too little screen time to present any special depth beyond the crooked Svengali that he looks and acts like, and his presence becomes the most consistent of the three, although he is the least important. So what could Rossen have done instead? Well, since The Hustler is unable to successfully resolve its two parallel arcs despite a very generous running time for a chamber-play (134 minutes), the simplest solution is to give priority to one theme over the other, rather than trying to juggle both. In spite of the many fine relationship scenes with intimate, naturalistic dialogue, it is the Minnesota Fats pool game that defines The Hustler and provides its raison d'etre. Adding the fact that the pool sequences generally display strong, distinct direction, this becomes the natural selection for main theme. The psychological trinity offers substantial room for trimming down, if one is prepared to accept it as a sub-plot that gives Felson and the movie a certain depth, rather than a main thread. From this decision it is easy to see the option to remove several scenes in the second half where the delicate psychological interplay is sacrificed for overstated neurosis; a cutting back of the only moderately interesting dialogues on moral between Scott and Newman can be effectuated in the same process. Felson is offered not less than three father figures where one (his first financier) would have sufficed, and again it is no great loss to turn Scott's broadly defined portrait of the 'necessary evil' into a less symbolic and more believable exploiter of talent. Finally, making the pool duels and their examination of will-power, maturity, and ego-centricity the dominating theme facilitates an improved division of screen time awarded the two Minnesota Fats games, extending the final game for dramatic effect at no narrative cost. What should not be excised is the entire introduction of Piper Laurie, a long and terrific sequence that is almost David Lynch-like in its enigmatic psychology and unpredictable dialogue. This finds The Hustler at its most modern, timeless even, and along with the Fats pool game justifies the high rating it is given by movie aficionados. Similarly, Eddie Felson's path to maturity needs a little more exposure, which will come naturally when some of the looser scenes around it are removed. The self-insight and growing up that Felson goes through comes not from his failed relationship with Laurie's neurotic character, but through his attitude towards the pool game and its associated vices of gambling, hustling and violence. This is another sign that Rossen should have elevated Felson the cocky pool player as the movie's main avatar, and kept Felson the free-spirited lover as a psychological extension. Script rewrite fantasies like the one you just read is a dubious and even provocative pastime, especially for a movie that is 40+ years old and brought home 9 Academy Award nominations (only the scenography and cinematography won; Piper Laurie probably deserved one). But I see this excursion as a testament to the strength of The Hustler at its best; one can only imagine what the entire movie would be like, had it all been as good as its strongest sequences. 7 of 10

Posted by Patrick at Lysergia

at 10:43 PM MEST

Updated: 28 September 2013 11:43 PM MEST

18 September 2013

Costa-Gavras' "Missing" (1982)

Now Playing: High Tide "Sea Shanties"

Topic: M

The resurgence of realism in 1970s cinema spawned two interesting sub-genres that combined naturalistic story-telling with Watergate fallout and an increasingly paranoid counter-culture. The first batch included political paranoia movies such as "The Parallax View", "Three Days Of The Condor" and "All The President's Men". In the early 1980s, as the Golden Age naturalism was falling out of favor elsewhere, a second wave of intelligent political thrillers set on foreign ground emerged, usually with a journalist at the center. These include "The Year Of Living Dangerously", "Under Fire", "The Killing Fields" and, as the genre's arguable swansong, Oliver Stone's "Salvador" (1986). It is fitting that one of the earliest movies that helped define this sub-genre was made by Greece's Costa-Gavras, who originally made a name for himself with the powerful "Z" back in 1969 and continued to make political movies in Europe through the 1970s. In 1981 he got to make his first Hollywood feature, based on his own script which in turn built on a book about actual events in Chile during Pinochet's military coup in '73. "MISSING", as the resulting movie was defensively titled, tells the story of a middle-aged American (Jack Lemmon) who travels to an un-named South American country to find out what happened with his son, a naive young writer who had begun to take an interest in an on-going military coup. The father is assisted by his daughter-in-law (Sissy Spacek) who has developed a substantial cynicism regarding both the local regime and the American embassy's futile efforts. The movie chronicles their search while details about the missing son's inquiries are presented partly in flashback. What's great about this genre is that it provides both a setting, a storyline and a mood that are naturally engaging. 1970s aesthetics demanded that everything be shot on location or in totally convincing sets, and from there on it's mostly a question of the psychology and interplay of the protagonists. And "Missing" gets very strong in this department, once Jack Lemmon steps off the plane and begins to interact with unreliable US diplomats and Spacek's crass defaitism. Both of the main parts are strongly written, and it's a delight to see Lemmon and Spacek click like clockwork, despite their great difference in age, as they overcome their natural skepticism towards each others. The quest for the missing son is the engine of the storyline, but, as tends to be the case in these foreign policy thrillers, the characters of the protagonists is what makes the scenes work. It's fascinating to see Lemmon's brilliant old skool method acting connect seamlessly with the dark, late-phase realism of "Missing". Costa-Gavras strove to create a fairly commercial movie that in theory could work as a straight-ahead crime story, as evident from the substantial efforts put into making the repetetive settings (hotel room, lounge, embassy) look a little different each time. An intellectualized work may have exploited this limitation to create a Kafka-esque milieu (think "Barton Fink") but with new camera settings and changed lighting, boredom from stasis is avoided. Like all movies in the style, there are grim images of dead bodies stapled high to fill an entire morgue basement or left to rot out in the streets, and live executions before the camera. These things, and much else in "Missing", can also be found in the small wave of similar movies that followed in 1983-86. I would like to proclaim this a 'great' movie, but unfortunately I can't. I'm not one to fret over plot holes, especially not in sci-fi and fantasy movies which are all make-believe and illogical by their very nature. In more realistic cinema, the demands are naturally higher, but it would still have to be a fairly major plot hole for it to affect my overall opinion. This is going to be pretty spoiler-heavy, but I want to lay the entire thing out on the chance that someone can correct me and explain that it's not a plot hole at all! As the movie progresses, attention moves more and more towards the research activities of the missing son Charles (a somewhat bland John Shea) prior to his disappearance. The narrative flow turns non-linear with flashbacks and even 'hypothetical' scenes, which jars with the fundamental realism convincingly established. Moving into the third act, the viewer unexpectedly learns that the young man's inquiries about the coup had been much more substantial than what was revealed earlier in the movie. In other words, the viewer is first shown a partial flashback, but the most important aspect of the flashback sequence is withheld until much later. This is not a very elegant way to emphasize the thriller aspect of the movie, and it indicates an indecisive compromise with commercial demands. In order to justify this curious breaking up of a simple, linear storyline, Costa-Gavras lets the left-behind note book of Charles reveal these deeper and more dangerous inquiries he had made, as Lemmon and Spacek read them. The reasons for the military regime and its corrupt US supporters to get rid of the troublesome young American now become much clearer, and after this insight the final resolution to the quest comes as no surprise. The cause and effect link is thereby rescued, but the normal conventions of story-telling are violated in order to maintain a sense of mystery until the final reel. Any cineast will feel an unpleasant tingling in the back of the head from the director's tortured wrangling with plot, factual data, and studio expectations. Truth is, there isn't much of a thriller or detective story in the "Missing" story, and it's unfortunate that Costa-Gavras, after nailing the characters, dialogue and moods so very well, forces his hand to break not only dramatic logic, but also rules of the style. Without having checked, I believe that none of the 4-5 movies I mentioned above contain flashbacks and certainly not chopped up flashbacks. But this is not the actual plot-hole, just its origin. Since the story was forced into the non-fitting mold of a mystery thriller, Charles' note book aquires a central role in revealing the full nature of the case. This, however, falls apart pretty fast, since the note book has been on hand throughout the movie--it's not like it was discovered in a hidden drawer or a bank vault. Spacek, as the missing Charles' wife, had the note book within reach all the time, and at least two early scenes refer to his detailed note-taking. So, logically, one of the first thing Spacek's character would do, is to go through his note book and see if there are any clues to what happened to him. But she doesn't do this until near the end of her and Lemmon's quest, which is particularly annoying since there are indeed clues in it to what happened to Charles (i e: his detailed coverage of American involvement in the coup), which she would have used to go to media or press the case harder with the US embassy. But the plot hole is actually even wider, because it is unlikely that Spacek needed to read Charles' notes to find out what was going on with the coup--their social circle were all young counterculturists and discussed things like this with great interest. It seems quite unlikely that Charles, and the female friend who accompanied him (Melanie Mayron) didn't tell Spacek and their liberal friends what he had found out from the US military personnel he chatted with. It was big news, and also excellent gossip. The third and final problem arising from this plot hole concerns the same female friend, who was present when Charles did his inquiries, and must have known just as much as he did about the foul play behind the coup. And unlike Charles, she wasn't dead or even arrested, and the Spacek-Lemmon investigative team could simply ask this female friend if Charles knew anything that might have been a risk for him. Which of course he did, and which the friend knew all about, and could have told them at any point. Instead, the friend is conveniently written out of the script about halfway through. "Missing" treats Charles' notes as though they alone held the mysterious data he elicited, even when the movie had already shown us that at least two more people undoubtedly knew it all. Again, this wouldn't have been a big deal if it hadn't concerned the central axis of the storyline. As it is, it becomes a stumbling block for any attentive viewer familiar with genre conventions and plot devices. Once one starts pulling at the loose thread of this non-secret note book, other problematic strands emerge, and one is left sitting with a movie which was on its way to greatness, but sacrificed it for the sake of inserting a dramatic mystery where one wasn't needed. It's not necessarily the Hollywood studio's fault (after all, Costa-Gavras wrote the script) but the suspicions would seem to go in that direction. Ah, too bad. Still, a movie with many fine elements, most of them involving Jack Lemmon and Sissy Spacek. 6 of 10

Posted by Patrick at Lysergia

at 10:08 PM MEST

Updated: 29 September 2013 12:01 AM MEST

10 September 2013

Topic: *Memorabilia & such

Posted by Patrick at Lysergia

at 11:11 PM MEST

8 September 2013

Serpico inspected

Now Playing: The Wheels "Road Block" CD

Topic: S

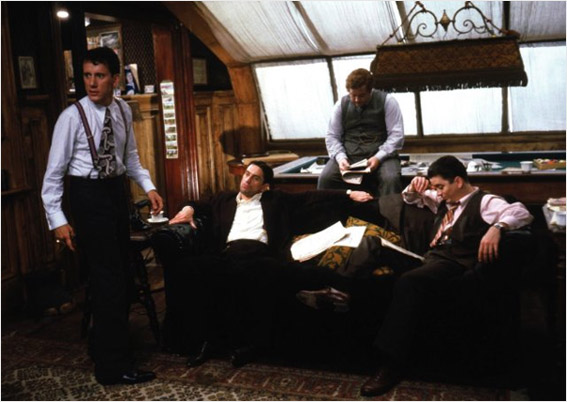

Our old friend Sidney Lumet was handed the reins on SERPICO (1973) with short notice, replacing John Avildsen shortly before shooting began. Presumably a complete shooting script was already in place, which didn't keep Lumet from making a film with recognizable qualities in both craftsmanship and aesthetics. Based on a novel which in turn was based on a true story about NYC police corruption, one has to wonder how Hollywood would have handled this material today, or whether the same script would even have been green-lighted, Oscar nomination or not. Serpico rests on three distinct legs, which was and should be considered enough for a stable foundation. One is the New York City milieu, captured beautifully as too-honest cop Frank Serpico (Al Pacino) gets transferred from borough to borough. Shot entirely on location, we see the great city at its most run-down and naturalistic, before any gentrification and zero tolerance moved in. Only a couple of years separate these streets from those in Taxi Driver, and I almost expected Pacino's Serpico to bump into De Niro's Travis Bickle in some street corner. Although I suggested earlier that Lumet's direction seems most at home in distinct, enclosed spaces, the reels of Serpico breathe with the exhaust fumes and fast food smell of a restless inner city. It's not a question of stylish direction as much as a selection of ideal shooting locations, a parade of exposed brick walls, withering brown-stones and abandoned shopfronts. The second asset is Mr Al Pacino, smartly nabbed for a leading role between Godfather I and II. Obvious as the praise is, the performance shows the man at the absolute top of his game, clearly rejoicing in a role with a wide emotional range and plenty of room for method acting expressionism. But his most important contribution isn't the credibility brought to this complex character as much as the subtly stated trajectory of maturing that takes place underneath the latinesque flamboyancy, a development of particular importance in a movie where the narrative story arc is unsteady and repetetive. Which brings us to the aspect hinted at above, the nature of Serpico's story as a story, and how it may be considered unfilmable today. Because there is no grand plot that unfolds in this script; rather a sequence of almost identical cycles in which the protagonist arrives at a new police district, refuses to partake in local bribery, becomes victim of a freeze-out, and is ultimately forced to leave. This scenario is repeated, with very little variation, four times during the 2+ hours the movie lasts, and the parallel plot of Serpico trying to engage 'outside agencies' is equally repetitive as various high officers turn out to be corrupt in their own ways. Any storyteller's natural instinct would be to cut and compress all this into a couple of anecdotal instances that clarify the theme and struggle, and develop a more conventional hero-narrative around these key structures. But in the early 1970s a lot of things were possible and new models tried out, and so this true life saga remained a naturalistic zig-zag path between hope and despair, seemingly dictated by randomness rather than myth. As mentioned above, Pacino outlines a steady trajectory underneath his mood swings, but this would not have sufficed as backbone if Sidney Lumet hadn't also put his vast film-making skills into making Serpico's tale a working cinematic experience, rather than a "60 Minutes" special on police corruption. The gold is in the details, like the casting of a long line of unknowns with memorable, often brutal faces to play crooked uniform cops, or the way a police station looks exactly like you imagined it*, or the fact that Serpico's girlfriends do not resemble Raquel Welch but ordinary NYC hippie ladies. There are a few missteps where the desire to make every scene memorable means adding awkwards details, but aesthetically Serpico is a triumph, and probably one of the main inspirations for Ridley Scott's period recreation in American Gangster. At the end of the day, though, Frank Serpico's tale doesn't really carry enough weight or originality to communicate across the decades, and even less so at an overlong 130 minutes. The producer's choice to stay away from typical Hollywood mythification and tell the story as it was (by and large) is wholly commendable, but it also set a ceiling for how powerful a movie experience one could deliver. Thanks to Lumet's professional commitment and Pacino's multi-layered performance, the finished result came pretty close to that ceiling. 7 of 10

* along with French Connection, Serpico provided a blue-print for the look and tone of TV cop series for a dozen years ahead.

Posted by Patrick at Lysergia

at 9:59 PM MEST

Updated: 8 September 2013 10:10 PM MEST

20 August 2013

Elia Kazan's "The Visitors"

Now Playing: Drifters "Fools Fall In Love"

Topic: V

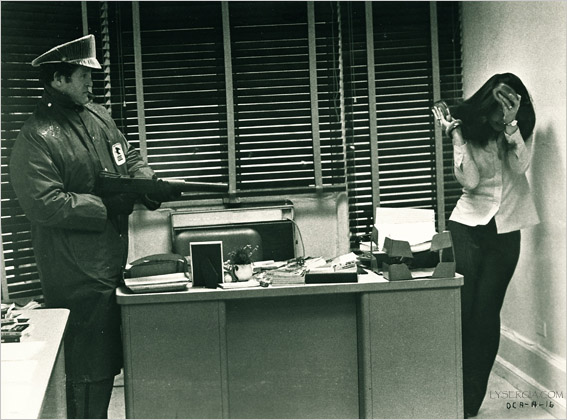

At some early point in his career, James Woods decided to have a substantial nose job. The surgery was a success, retaining Woods' memorable features while trimming the snout down from a radical Karl Malden-like appearance to a less conspicuous Dustin Hoffman dimension. The reason I know this is because I just watched Woods' very first movie, THE VISITORS (1972), in which the profile shots in particular reveal a different face than the one that became famous in the '80s. A more obvious starting point for The Visitors might be the observation that this is one of very few post-'50s movies directed by the great Elia Kazan, once prince of Hollywood and maker of stars like Marlon Brando and James Dean. I'm not entirely sure, but I would guess that the empty hole that Kazan's filmography turns into from 1958 onwards is fallout from his notorious disclosure of commie names in the McCarthy hearings. It is said that Hollywood has short memory, but in the matter of HUAC the shadow from Kazan's testimony would grow to cover several decades, not allowing him back into the fold until an honorary Oscar in the late '90s. That this was a great loss for American movies is a given, and even a minor work like The Visitors demonstrates what Kazan could have done in the '70s, a period when many of his disciples were revolutionizing studio films in both directing and acting, and where he likely would have found himself right at home. The synopsis and script are quite good and give strong indications of being adopted from a stage play or even a novella, but reportedly was the creation of Kazan's oldest son. True or not, it is a psychological drama that delivers a slowly mounting tension around five people during a couple of days and nights in a rural house. For those familiar with Casualties Of War (later filmed by Brian de Palma with Michael J Fox), The Visitors examines the interesting notion of a sequel to that story, asking what might happen if two army buddies paid their whistle-blower colleague a visit a few years after the events in Vietnam, when they're all back in the US. This backdrop is not revealed until halfway into the movie, and two differing accounts are given with no obvious priority for the viewer, which is another indication of the mature intelligence behind The Visitors. Inevitably the mood grows darker and more threatening, and a fascinating power struggle between the leading visitor (Steve Railsback) and the young mother in the rural household (Patricia Joyce) brings the viewer through several complex scenes, as the woman struggles to understand the brutal actions in the past while also trying to offer a forgiveness of sorts. Meanwhile her defensive husband (Woods) tries to keep his mind off the events of the past and his possible guilt as a 'snitch' on his plutoon comrades. But the relentless plot machinery of The Visitors brings these threads to an inevitable confrontation and resolution much in line with the realistic-nihilistic perspective often expressed in New Hollywood movies.  Indeed, one of several noteworthy things about The Visitors is how modern it feels--in some ways it's actually more like an indie 1990s movie such as Sean Penn's Indian Runner than the often eccentric auteur works of the '70s. Undoubtedly a deliberate choice, there is none of the hippie or counterculture stylings usually found in early '70s films, which contributes to its timeless feel. Shot on a low budget with a small crew, Kazan manages to make terrific use of lighting inside the rural house, where Steve Railback's eerie, unpredictable character is frequently shown with his eyes cast entirely in darkness, while James Woods' pock-marked, skinny face is presented brightly for the viewer to illustrate his relative naivetë. The movie's shoestring production is evident in a couple of scenes where the lighting is completely wrong, for which there apparently weren't enough resources to re-shoot. Indeed, one of several noteworthy things about The Visitors is how modern it feels--in some ways it's actually more like an indie 1990s movie such as Sean Penn's Indian Runner than the often eccentric auteur works of the '70s. Undoubtedly a deliberate choice, there is none of the hippie or counterculture stylings usually found in early '70s films, which contributes to its timeless feel. Shot on a low budget with a small crew, Kazan manages to make terrific use of lighting inside the rural house, where Steve Railback's eerie, unpredictable character is frequently shown with his eyes cast entirely in darkness, while James Woods' pock-marked, skinny face is presented brightly for the viewer to illustrate his relative naivetë. The movie's shoestring production is evident in a couple of scenes where the lighting is completely wrong, for which there apparently weren't enough resources to re-shoot.

Mention must be made of a sub-plot involving the young woman's father, a middle-aged writer who lives on the property, and is smitten to relive his own violent army past in the company of the two visitors. Even if a minor thread in the storyline, it's very skilfully handled in both writing and acting, as the obscure TV actor Patrick McVey delivers a naturalistic performance that would have made Gene Hackman proud. The father's instinctive attraction towards the 'evil' side of the visitors precludes the dark but logical turn of events during the final act, giving further support to a view of the world that is fatalistic and cynical and, again, quite modern. Kazan always preferred to work with unknown actors, and The Visitors marks the screen debut not only for James Woods (who is OK, but lacking full commitment) but also for Steve Railsback, who delivers the most memorable performance of the four main parts. Known mostly for his part as Charles Manson in Helter Skelter (1976), Railsback has a natural eeriness and charisma that is not unlike Jeremy Sisto, and it's a shame that he has done mostly B and C-movies after a decent run during the 1970s. Further proof of Kazan's skill in casting was Patricia Joyce, who essentially both came and went with her admirable performance in a complex role that is arguably the core wheel of the entire film. It may be due to a poor digital transfer rather than cheap film stock, but my DVD of The Visitors was both grainy and washed out color-wise, making it look almost like a blown-up 8mm film at times. It was easy to adjust to however, as the storyline and acting demanded attention from the very start and never once broke its trajectory. There are a few minor objections to be made with reference to the undeveloped character of the second ex-army visitor, a tendency towards grimness over precision, and of course the question how this would have come across with a full Hollywood budget (e.g. the sound is clearly below par), but ultimately The Visitors is an experience that is fully satisfactory as it is. 7 of 10

Posted by Patrick at Lysergia

at 10:06 PM MEST

Updated: 20 August 2013 11:29 PM MEST

18 August 2013

Now Playing: The Satans c1965 LP

Topic: *Memorabilia & such

Posted by Patrick at Lysergia

at 11:04 PM MEST

12 August 2013

Eyes Wide Shut lament

Now Playing: Grateful Dead 2/11/69 Fillmore East

Topic: E

Much like the 'Gomer Pyle' problem (see Full Metal Jacket comment) I've been waiting for the coin to drop regarding the master's last cinematic offering, EYES WIDE SHUT (1999). On first viewing it seemed kind of slow-moving and with a curious insistence upon certain elements which didn't seem particularly eyebrow-raising, such as the main couple's potential infidelity, or the extreme secrecy of the VIP sex mansion. It also featured a number of marvellous scenes, not least the opening ballroom with its unearthly lighting and flawless direction. And while the mansion swinger party seemed off-target, the best scenes in there (primarily when Tom Cruise's protagonist is exposed) had the Kubrickian magic that sticks in your memory forever even after just one viewing. All in all, I assumed that these high points hinted of the potential power of the entire movie, once I had fully integrated it... because this is how Kubrick films tend to operate for me. But after catching Eyes Wide Shut on late night TV the other day, I'm afraid the verdict must be the same as on 'Gomer Pyle': it just doesn't work. And here we're talking about a whole movie, not just certain scenes with a non-protagonist character. I actually felt embarrassed on Kubrick's behalf as I watched the "so what" sequences of infidelity and open sex that he makes such a fuss over, as though he was some old man out of touch with the modern era. I don't think that was the true problem, but rather something connected with his literary inspiration (Arthur Schnitzler's 1926 novella) for the movie, and how he personally viewed the themes he dealt with. Happily married for 40 years, and not one likely to deal in casting couches and Charlie Sheen style whore binges, one must wonder just how much Kubrick understood of the material he dealt with in Eyes Wide Shut.

With a rising amount of pain I watched the scene where Sydney Pollack passes on a warning to Cruise's confused doctor to stop his inquisitions about the mansion. The scene is inexplicably drawn out, with long pauses between the lines, even as the dialogue is quite ordinary film noir fodder. Pollack's character displays a completely overstated embarrassment for the whole affair, which jars strangely with the opening of the movie which finds him revealing to Dr Harford (Cruise) that he was having sex with a drugged out young prostitute. Given such a lifestyle, why should this wealthy New Yorker feel any hesitation whatsoever in telling a young doctor to stop snooping where he doesn't belong. The scene just doesn't make sense, and the dialogue is bland and predictable, and the pace grinds to a complete halt. It's ironic that the room has been equipped with a very Kubrickian red pool table instead of the customary green, creating a red rectangle which almost seems to float by itself and adds a grim tone to the scene... which fails in almost any other way. But it's not individual scenes, some of which are in fact brilliant, that weigh Eyes Wide Shut down--it is the treatment of the material, and the emphasis on what seems to be the wrong elements. It is, in the 2000s, hard to understand why Cruise's doctor reacts so strongly when his wife (Nicole Kidman) reveals an old sexual fantasy for him. It simply isn't very shocking, and since the viewer does not understand the young doctor's reaction, it becomes hard to empathize with him. Similarly, why would a secluded mansion where VIPs meet to have free sex be such a big deal that people get killed for it, and that others are threatened to their lives? The only thing we see in there are a bunch of cool masks and people performing completely normal sex acts. So what? While one can't say for sure that these things occur in precisely this way, I doubt many would be surprised if it was revealed in this day and age. As the movie neared the end I kept thinking that it would have been much more credible and effective if the mansion orgies had been harsh S & M stuff, where people bled and wept, and others acted out sick fantasies, and call girls died not because of some mysterious omerta, but as an effect of the violent sexual practices. This would also have formed a more impressive nadir for the protagonist's night journey into himself, and contrasted sharply with the cozy Manhattan family residence of the doctor and his wife. The final misstep occurs when Mrs Harford unexpectedly has found the costume mask that her husband just had stashed away in a safe, and in a dramatic gesture places on his pillow. Again, why is this mask such a big deal--and why would she suspect that it is? Maybe it was a gift he was planning to give her? Instead he breaks down and promises to tell 'everything' about his night on town, and again the whole thing seems bizarrely overstated and, I hate to say this, old-fashioned. 6 of 10

Posted by Patrick at Lysergia

at 11:26 PM MEST

Updated: 12 August 2013 11:32 PM MEST

9 August 2013

Figures In A Landscape (1970)

Now Playing: Fox on RD Records

Topic: F

Although a very strong period for cinema, the early 1970s had its share of smaller movies that time has allowed to fall through the cracks of public amnesia. Despite its forgotten status today, FIGURES IN A LANDSCAPE (1970) displays no shortage of strong 'names', directed as it was by the renowned Joseph Losey and with the powerful screen presences of Robert Shaw and Malcom McDowell in a double protagonist set-up. The movie could be construed as an action feature with certain parallels to Stanley Kramer's The Defiant Ones (1958) and Steven Spielberg's Duel (1971), as the swiftly moving camera follows the two men on a seemingly endless escape through an unidentified country in what looks like Northwestern South America. People are killed, including an entire army garrison and some unlucky passers-by, as 'Mac' (Shaw) and 'Ansell' (McDowell) fight their way towards survival on the other side of a snowy mountain range. Always on their heels is an ominous black helicopter, and soon also a large army posse. The two leads walk, run, crawl, limp, swim and climb their way towards freedom, while eating canned food and bickering about their next move. The ending needn't be revealed here as it's a movie worth seeing, which can be discussed without this knowledge. However, I believe better milage is drawn from Figures In A Landscape if one approaches it as a character study of two strong-willed individuals in duress rather than a thriller. There is a certain undertone of experimental '60s theatre in the script (written by Shaw from a novel, incidentally), even with the abundance of beautiful, sweeping location shots of equatorial valleys, prairies and mountains*. Unlike a conventional thriller the viewer is never informed of the background for the opening premise of the two men on the run, and their individual stories remain opaque for the bulk of the movie. Shaw's older and slightly eccentric character slowly begins to reveal his past marriage in the form of well-rounded anecdotes which point forward to his unforgettable appearance in Jaws. There are some interesting similarities between 'Mac' and Jaws' 'Quint', which raises the question if maybe Spielberg had this movie in mind when he perfectly cast Shaw as his shark-hating sea captain. McDowell's 'Ansell' remains more enigmatic simply because he has much fewer lines to work with, but the impression of an upper middle class boy from Swinging London comes across; clearly closer to his role in the preceding If... than the succeeding A Clockwork Orange. Losey makes good use of McDowell's cat-like appearance and gives his body language a smooth grace completely lacking from Shaw's rural rough-neck. The two leads never really 'click' on the screen in the way familiar from modern buddy movies, but each delivers a fine performance under shooting conditions which must have been quite harsh at times. While not quite an action movie, Figures In A Landscape does not take its symbolic and archetypal potential very far; as an example it's not like the Darwinistic survival showcase found in The Edge (1997; script by David Mamet), nor does it invoke Beckett-ish problems of communication and identity otherwise in vogue in European '60s drama. Unfortunately, the dialogue and psychological interplay is not sharp enough to work as pure '70s naturalism, and except for the excellent helicopter shots the action scenes aren't impressive if using a pure thriller label. Ultimately it becomes a rare case where the viewer might wish for a more pretentious undertone; either that, or a purification of the dual fugitives theme, which undoubtedly is how the material would have been handled in modern Hollywood. This odd bird in Losey's oeuvre was nevertheless enjoyable; good casting, plenty of outstanding panorama shots of a uniquely varied landscape, and a backbone of experienced movie crafting made for 90 minutes well spent. 7 of 10

*This must have been a fairly early movie to employ the front-mounted helicopter camera technique used in almost every action movie today; these shots look like fully modern cinematography.

Posted by Patrick at Lysergia

at 9:45 PM MEST

Updated: 9 August 2013 10:20 PM MEST

A few grumpy remarks on Midnight Cowboy

Now Playing: Van De Graaf Generator

Topic: M

Like The Graduate, Easy Rider and to some extent Bonnie & Clyde, it seems to me that MIDNIGHT COWBOY (1969) has received an exaggerated standing in modern movie history, in comparison to its intrinsic qualities as a film. These four works all contained elements not previously seen on the silver screen, and for that reason and their timely arrival, they are often perceived as vital stepping stones towards the golden era of New Hollywood. Each one of them deserves thorough scrutiny from the vantage point of today. Seeing Midnight Cowboy for the first time in many years, I find its position as a bridge between eras one of the more interesting aspects. The urban naturalism, the eccentric personalities, the psychological sub-texts and the focus on character and moments instead of plot and pacing, are all things typical of the auteur-driven 1970s cinema. But what is less commonly observed in the movie is the substantial residuals from early-mid '60s aesthetics, which inform it as much as the gritty realism. This is not a smooth blend, as the more creative Anglo-American '60s movies stood in almost complete stylistic contrast to what would follow in the next decade; they were flashy, pretentious, experimental for their own sake, star-struck with divas and VIP's, obsessed with themselves and with their own time. It is, to my mind, not a creative period that has aged very gracefully, as a revisit to Antonioni's Blow-Up might demonstrate. Director John Schlesinger had his briefcase full of Swinging London aesthetics when he arrived to take the reins on Midnight Cowboy, the content and themes of which MGM doubted any American studio veteran could handle. The end result is a stylistic pendulum that swings from the down-and-out reality of 'Ratso' Rizzo's (Dustin Hoffman) roach-infested apartment to the unexpected insertions of dreams, memories and fantasy montages, creating a badly jumbled artistic presence that offers us everything and nothing. Some of these segments border on the laughable with their unimpressive look and poorly motivated presence. Curiously, the one scene in which a 'fantasy' excursion might have been justified, the obligatory '60s drug hallucination of protagonist Joe Buck (Jon Voight), is restrained and brief. Other such scenes are longer and sometimes repeated, and hint of some dark events in Joe Buck's past, but the psychological link to the present-day 'hustler' is so vague that it's basically left dangling. I wouldn't want to spend too many words on this aspect of Midnight Cowboy, but the fact is that the vision sequences are both highly dated, poorly directed, and in conflict with the other main tone of the movie. I am not sure why Midnight Cowboy has remained so relatively immune to criticism. It's not a great movie; there are flaws easy to spot and difficult to defend, unless one chooses to laud it for its 'historical' vitality. Like The Graduate I believe that its treatment of previously untouched themes, along with a good match for the zeitgeist, caused people to mistake thematic boldness for cinematic quality. Movies like these, and there are many, tend to age badly. Another parallel to The Graduate is the presence of Dustin Hoffman, and again I suspect that his naturalistic performance, which pushes method acting into near-parody, was seen as a revelation at the time, since it was so completely different from his earlier role in Mike Nichols' film. During the '70s these thespian reinventions became commonplace, but in the late '60s Hoffman was ahead of the pack. Method or not, his performance doesn't cover very much range, and the make-up and endlessly ailing body removes any chance for this unattractive street survivor to evoke sympathy with the viewer, who may feel as if watching less a person than a persona, in the theatrical fixed-expression sense. Not that it's much easier to come to terms with the main character, a half-stupid Texan who arrives to New York City with plans to become a male prostitute, a situation most people will find hard to identify with. Jon Voight, who would become a very good actor later on (see Coming Home review below) probably portrays the character as intended, but much like Hoffman there is a sense of watching a distinct set of prepared faces and gestures, rather than truly immersive acting. The rest of the cast is forgettable, though it's nice to see an early role for Brenda Vaccaro, who in her 10 minutes on the screen delivers what passes for a female lead part in this very male-centric work. More could be said about Midnight Cowboy, but as it doesn't belong to the creative wave of New Hollywood in either style nor quality, I'm cutting the reel here. A final thought: both Schlesinger and Mike Nichols got very lucky by making the right movie at the right time. This single instance of timing and theme helped them build long A-list careers that more gifted directors only could dream of. 6/10

Posted by Patrick at Lysergia

at 12:50 AM MEST

Updated: 10 August 2013 12:18 AM MEST

5 August 2013

Mad Max 3: Beyond Thunderdome

Now Playing: Xebec LP

Topic: M

After the guys over at Cinefiles suggested that MAD MAX 3: BEYOND THUNDERDOME (1985) is in fact a really good '80s action movie, I became quite interested in seeing it again. My memories of the original run were disappointing enough that I had basically filed it away in the 'never revisit' drawer, but 25 years on the possibility that things had changed with time has to be considered. Except for Mel Gibson's giant '80s poseur metal hairdo and the tragic loss of his trusted V8 car, Mad Max 3 begins strongly enough. Heading ever deeper into the wasteland, the story is set in what's partly a real sand desert where Max comes upon a trading post large enough to be called a town, built from the debris of the apocalypse. The sets and characters are full of oddball ideas while still continuing the edgy, cynical tone of the earlier movies. Action-wise the steel-cage fight with 'Master-Blaster' is what everyone remembers from the film, but the entire Bartertown segment is solid dystopic action. Apparently George Miller half-abandoned the movie project due to the death of a friend involved, but his hand is clearly present in this promising opening act, which may also recall Paul Verhoeven's satirical sci-fi movies from the same era. But with Bartertown's resources exhausted in both concrete and thematic terms, Mad Max is on the road again, and here the problems begin. The rest of the movie deals with a colony of children who survived a plane crash during the apocalypse and found a paradisiacal valley in the wilderness, where they lived ever since. It's sort of like Lord Of The Flies meets Peter Pan, and few people, now or back in 1985, seem to like it. The problem to me isn't so much the content or execution of the idea, which has a few neat moments such as the confused tribal mythology the kids have created, but the idea itself as placed inside a Mad Max feature. The Max movies are basically action pieces set in a near future, but the Children's Colony segment is real science fiction, complete with Messianic parallels and philosophical brooding. It's simply not in the same genre as the franchise that gave us the Road Warrior, and so the second half of Beyond Thunderdome was pretty much dead on arrival the moment it went beyond thunderdome. The movie ties the two stories together in the most flippant, uncaring manner (i e: Mel and the kids go back to dangerous Bartertown to seek out the 'Master' for the reason of... what, precisely?) which does demonstrate Miller's absence from the creative chair in a rather painful way. The closing car/train chase is also poorly motivated by the script (in stark contrast to Mad Max 2) and seems to be there mainly to please the audience. It's not bad, but really just a half-assed retread of the magnificent final reel of Road Warrior. The bad guys too are a pale shadow of Lord Humungus and Wez, and while Tina Turner does a fairly good job and seems to enjoy herself as the local Queen, her casting is somewhat distracting, not least since the rest of the new cast is unmemorable. He got lucky with picking a near-unknown Mel Gibson for the franchise lead but otherwise, casting is clearly not one of George Miller's strengths. Sorry to disagree with the Cinefiles but Mad Max 3: Beyond Thunderdome isn't a very good movie; worth seeing but not more. 6/10

Seeing Road Warrior and Mad Max 3 in rapid succession served as amusing reminders of what a xerox copy job Kevin Costner's Waterworld is of Miller's creation.

Posted by Patrick at Lysergia

at 11:26 PM MEST

Updated: 10 August 2013 12:19 AM MEST

29 July 2013

Brief praise for Mad Max 2: The Road Warrior

Now Playing: Canadian garage comp

Topic: M

Not only was the ROAD WARRIOR (1981) one of the truly great action movies of the 1980s, but it has also aged extremely well. The basic dystopic future vision seems as possible or maybe even more possible now than when I saw this during its original run, and the action sequences haven't dated one iota. The relentless 20 minutes that close the movie are still the greatest road battle sequence ever committed to film, and may in fact never be topped. The closest I can think of is the freeway chase in Matrix 2, but they got to cheat with both super-powers and CGI tricks, and still couldn't match George Miller's intense precision. In addition to the rare cinematic skill on display, the final road chase is fully motivated and in fact necessitated by the logics of the script, which adds to the nail-biting attention it commands. Everything rides on that trailer rig breaking through, without it the whole movie falls to pieces. Of course, everyone knows this already, and I don't really have much to add regarding the second Mad Max instalment, except to testify on its lingering greatness. One thing I hadn't really reflected on earlier is how consistent the movie is in its presentation of the lone survivalist as reluctant hero. Mel Gibson is in every scene in the movie, yet he rarely says a word and hardly ever changes his expression of contained torment. According to IMDB he only has 16 lines of dialogue in the entire 90-minute movie, which sounds extraordinary but may be true. This is not style for style's sake but a reflection of a story so thoroughly trimmed down to the raw essentials that there isn't a wasted moment in it. Literally everything you see in The Road Warrior, every line and event, is there for a discernible reason. This is how action movies were made once upon a time*; no useless padding out of the playtime with unwarranted subplots (see Looper review), but a tight roller coaster ride that grabs you by the neck from the start and doesn't let you go until you got your money's worth. Let's bring it back. 8/10 NOTE: after writing the above I see that an 'independent variation' on the Mad Max trilogy is in post-production, directed by Miller and with Tom Hardy replacing Mel Gibson as Max Rockatansky.

*The same applies to another dystopic action classic from the same year, John Carpenter's Escape From New York, whose first hour or so displays a supremely tight flow.

Posted by Patrick at Lysergia

at 8:10 PM MEST

Updated: 10 August 2013 12:19 AM MEST

27 July 2013

Mad Max Arises

Now Playing: Zombieland

Topic: M

Because of the season, or because someone who actually thinks that movies are fun is in charge, but local TV has pulled out a surprising string of cult movies and unjustly forgotten nuggets the last few months. The other day we were treated to George Miller's MAD MAX (1979), a local Australian production which to my knowledge never has been broadcast here before. And it was a very good print too, obviously a recent digital transfer. Although Miller and the Mad Max franchise would go on to Hollywood success in the 1980s, this first instalment carries its low-budget origins with pride. Taking a page or three from the Roger Corman school of production, Miller shrewdly makes his finances go along way, squeezing out tension and valuable minutes of screen-time from sequences of smartly staged shots of cars and bikes zooming across the empty Australian prairie. In fact, already here you can see that Miller had a unique talent for shooting road action, something which became dazzlingly clear with the ROAD WARRIOR. A few different camera positions are utilized, some which clearly required special built side-cars and contraptions, and with a nicely paced editing the result is a more concentrated variant on the late '60s biker movies. Australians are known for their obsession with cars, something which colors Mad Max throughout--the only thing Mel Gibson's main character seems to be interested in except his young family is cars, and their advantages and problems. The bad guys all ride motorcycles, naturally. The future Australia of Mad Max isn't quite as dystopic as that of the sequel, but you can see it getting there. In a sense the Road Warrior is as if Mad Max has left the coastal grassland of the first part and gone into the wilderness of the desert inland, where he finds a more primitive and deeper expression of the on-going collapse. Mad Max is impressive in most respects, even without the Gibson and Miller aura, and its particular form of dystopia was ahead of its time in the late '70s. In addition to Corman there are traces of Straw Dogs and revenge movies in the Death Wish tradition, and there is clearly an exploitative aspect. Yet Miller takes care to deal with needed scenes of romance and hanging out, and gracefully handles the peripeti (turning point) scene that could have ruined the whole movie. Gibson's acting is somewhat unsteady and he also has to handle some bad dialogue (a persistent weakness of the script), but it's interesting to note some of the trademark expressions and body language that he later would use to define his acting style (in Lethal Weapon more than the Road Warrior). Unfortunately Miller chose to present the evil opponents as a bunch of crazy hippies which strips the movie from some of it emotional charge, even more so since the acting among these thugs is fairly weak across the board. It's possible that the Manson Family spectre still loomed over the murder gang image at this point (along the lines of the Dirty Harry The Enforcer movie), but alas these bikers lack the Family's sinister presence. This, along with the uninspired dialogue, betrays Mad Max' B-movie origins and keeps it from being a full-blown indie classic, but it's still a skilfully done and fairly original work. 6/10

Posted by Patrick at Lysergia

at 12:23 AM MEST

Updated: 10 August 2013 12:20 AM MEST

25 July 2013

Looper up and down

Now Playing: Michael Angelo on Guinn

Topic: L