| « |

October 2024 |

» |

|

| S |

M |

T |

W |

T |

F |

S |

|

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

| 6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

11 |

12 |

| 13 |

14 |

15 |

16 |

17 |

18 |

19 |

| 20 |

21 |

22 |

23 |

24 |

25 |

26 |

| 27 |

28 |

29 |

30 |

31 |

Reflections of the Third Eye

8 September 2013

Serpico inspected

Now Playing: The Wheels "Road Block" CD

Topic: S

Our old friend Sidney Lumet was handed the reins on SERPICO (1973) with short notice, replacing John Avildsen shortly before shooting began. Presumably a complete shooting script was already in place, which didn't keep Lumet from making a film with recognizable qualities in both craftsmanship and aesthetics. Based on a novel which in turn was based on a true story about NYC police corruption, one has to wonder how Hollywood would have handled this material today, or whether the same script would even have been green-lighted, Oscar nomination or not. Serpico rests on three distinct legs, which was and should be considered enough for a stable foundation. One is the New York City milieu, captured beautifully as too-honest cop Frank Serpico (Al Pacino) gets transferred from borough to borough. Shot entirely on location, we see the great city at its most run-down and naturalistic, before any gentrification and zero tolerance moved in. Only a couple of years separate these streets from those in Taxi Driver, and I almost expected Pacino's Serpico to bump into De Niro's Travis Bickle in some street corner. Although I suggested earlier that Lumet's direction seems most at home in distinct, enclosed spaces, the reels of Serpico breathe with the exhaust fumes and fast food smell of a restless inner city. It's not a question of stylish direction as much as a selection of ideal shooting locations, a parade of exposed brick walls, withering brown-stones and abandoned shopfronts. The second asset is Mr Al Pacino, smartly nabbed for a leading role between Godfather I and II. Obvious as the praise is, the performance shows the man at the absolute top of his game, clearly rejoicing in a role with a wide emotional range and plenty of room for method acting expressionism. But his most important contribution isn't the credibility brought to this complex character as much as the subtly stated trajectory of maturing that takes place underneath the latinesque flamboyancy, a development of particular importance in a movie where the narrative story arc is unsteady and repetetive. Which brings us to the aspect hinted at above, the nature of Serpico's story as a story, and how it may be considered unfilmable today. Because there is no grand plot that unfolds in this script; rather a sequence of almost identical cycles in which the protagonist arrives at a new police district, refuses to partake in local bribery, becomes victim of a freeze-out, and is ultimately forced to leave. This scenario is repeated, with very little variation, four times during the 2+ hours the movie lasts, and the parallel plot of Serpico trying to engage 'outside agencies' is equally repetitive as various high officers turn out to be corrupt in their own ways. Any storyteller's natural instinct would be to cut and compress all this into a couple of anecdotal instances that clarify the theme and struggle, and develop a more conventional hero-narrative around these key structures. But in the early 1970s a lot of things were possible and new models tried out, and so this true life saga remained a naturalistic zig-zag path between hope and despair, seemingly dictated by randomness rather than myth. As mentioned above, Pacino outlines a steady trajectory underneath his mood swings, but this would not have sufficed as backbone if Sidney Lumet hadn't also put his vast film-making skills into making Serpico's tale a working cinematic experience, rather than a "60 Minutes" special on police corruption. The gold is in the details, like the casting of a long line of unknowns with memorable, often brutal faces to play crooked uniform cops, or the way a police station looks exactly like you imagined it*, or the fact that Serpico's girlfriends do not resemble Raquel Welch but ordinary NYC hippie ladies. There are a few missteps where the desire to make every scene memorable means adding awkwards details, but aesthetically Serpico is a triumph, and probably one of the main inspirations for Ridley Scott's period recreation in American Gangster. At the end of the day, though, Frank Serpico's tale doesn't really carry enough weight or originality to communicate across the decades, and even less so at an overlong 130 minutes. The producer's choice to stay away from typical Hollywood mythification and tell the story as it was (by and large) is wholly commendable, but it also set a ceiling for how powerful a movie experience one could deliver. Thanks to Lumet's professional commitment and Pacino's multi-layered performance, the finished result came pretty close to that ceiling. 7 of 10

* along with French Connection, Serpico provided a blue-print for the look and tone of TV cop series for a dozen years ahead.

Posted by Patrick at Lysergia

at 9:59 PM MEST

Updated: 8 September 2013 10:10 PM MEST

22 April 2013

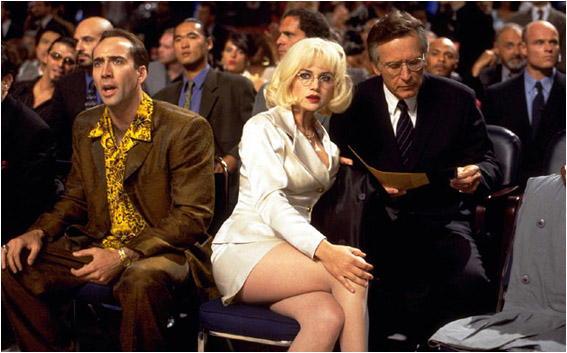

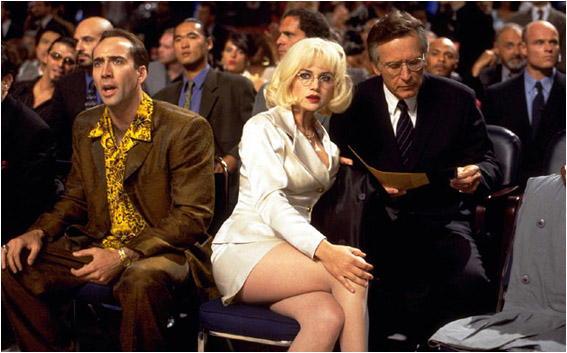

Snake Eyes (1998)

Now Playing: Creedence

Topic: S

Popcorn quiz: Brian De Palma made Snake Eyes because he (A) Wanted to do a single-take sequence that surpassed the one Scorsese had in Goodfellas; (B) Was curious about how Carla Gugino would look in tight silk clothes; (C) Figured he could use some of Nicholas Cage's hyper intense cocaine buzz presence while the guy was still A-list material? These are all valid reasons for making a movie, especially if you've paid your dues three times over like BDP had. Whatever his intentions, the end result is wholly and uniquely identifiable as his creation, which means that I enjoy it. In fact, I enjoyed it more on the second viewing than the first, and this is not due to some dubious theoretical insight like the intellectualized film student snobbery frequently hung around the director's neck. Au contraire, ma freres, I actually took greater note of the storyline and characterization this time. Not that it's particularly outstanding, but it's there for the viewer's attention, and I believe the dazzling single-take exposition offsets the balance of the entire movie on the first viewing. This extremely complex and magically realized tracking shot will probably be the only aspect of Snake Eyes to linger in the cinema annals, even if De Palma allowed himself a few loopholes (four or five camouflaged cuts during the 20-minute sequence) to make his mad enterprise work. Film students and movie-lovers alike enjoy the virtuosity and sheer fun of this grand opening, and unlike some of BDP's earlier showcases it is both appropriate to the theme and context of the movie (a big night with lots of tension in the air) and a very effective exposition which introduces the major characters and a number of details relevant to the mystery conspiracy that is the main plot element. The only problem, then, is that the viewer may still be digesting De Palma's tour de force and maybe hope for even more, while the storyline is rapidly evolving into new intricacies. The movie carries its comic book exaggerations with pride, and the sense of aesthetic playfulness is brought home by a dazzling use of bright colors in basically every shot, until the appropriately dark and murky ending. More movies should look like this, a true feast for the eyes on a level of pure, non-intellectual perception that makes it almost psychedelic, in the sense that hallucinogens can make each color look a little brighter than usual. Equally appropriate is the obvious use of studio sets for the entire movie, making everything look shiny new and slightly unreal. The casino where the action takes place is basically one gigantic set piece, and it's easy to imagine the fun De Palma and his assicoates had in designing the sets in combination with the fluid camera-work.  In accordance with the title there is a strong focus on eyes, in various symbolic and physical representations. Gary Sinise's sinister military officer turns the metaphorical 'snake eyes' of the title into an actual facial aspect, becoming less human and more cold and deviously reptile as the movie progresses. Perhaps this ocular theme justified use of POV flashback sequences (some which are actually 'false') that occur three times, but they are largely unsuccessful and distracts the viewer by inserting new dimensions to little effect. In typical BDP fashion the inspired creativity goes one step too far, but its more of an annoyance than truly damaging. In accordance with the title there is a strong focus on eyes, in various symbolic and physical representations. Gary Sinise's sinister military officer turns the metaphorical 'snake eyes' of the title into an actual facial aspect, becoming less human and more cold and deviously reptile as the movie progresses. Perhaps this ocular theme justified use of POV flashback sequences (some which are actually 'false') that occur three times, but they are largely unsuccessful and distracts the viewer by inserting new dimensions to little effect. In typical BDP fashion the inspired creativity goes one step too far, but its more of an annoyance than truly damaging.

Nicholas Cage was at the peak of his career around this time, and his hyper-active police detective seems determined to outdo the egocentric cocaine excesses seen in Face/Off. Unfortunately we are never told why his character behaves like a race horse on steroids. One might argue that Cage's performance is in line with the general larger-than-life tone of the movie, but it fails to add or expand on that tone, and makes for an awkward transition to the weary, disenchanted person he becomes towards the end. Gary Sinise on the other hand acts like he understands the movie completely, and while his performance also becomes weighed down by the exaggerated demands of the script towards the final scenes, the convincing military persona and gradually demasked 'snake' of the title is a major asset. Carla Gugino is very comic book-like as a reluctant heroine, actually more comic book-like than in Sin City, and while charming in presence her character isn't given enough respect by script or direction. The rest of the cast isn't bad but strangely forgettable, in view of how De Palma on occasion loads his movies with good casting and quirky minor parts. If you've only seen Snake Eyes once, see it again. I'm not so sure how it would hold up for a third viewing, though. 7/10

Posted by Patrick at Lysergia

at 2:08 AM MEST

Updated: 10 August 2013 12:42 AM MEST

20 April 2013

Spartacus (1960)

Now Playing: late night ambience

Topic: S

This is not a full-blown review of Spartacus, which you are likely to have seen and certainly owns no shortage of critique, from Kubrickians and others. Rather, I figured I'd post some random thoughts from my most recent viewing. The background you know; Kirk Douglas commanded the project and fired the original director after shooting had begun, in his place Douglas recruited the up and coming Stanley Kubrick, who had impressed the Hollywood star when the two collaborated on the much-respected Paths Of Glory (1957). Both Douglas and Kubrick embarked on the Spartacus rescue mission with their own private agendas, which didn't prevent the film from becoming a commercial and critical success. The first thing to observe is that the movie has aged fairly well. It looks and feels "old" in the sense of a classic Hollywood production, but only rarely does it seem dated. This era saw a number of ancient epics such as Ben-Hur, The Ten Commandments, El Cid et al. Of these, Spartacus is clearly the most relevant experience for a modern viewer. This is not due to some particularly brilliant directing from Kubrick, who does a skilful but fairly traditional job on the massive Cecil B DeMille type sequences, and lets the actors dominate the smaller scenes. One could say that if Kubrick's objective was to add a successful A-list movie to his resume', he did it just right. Thanks to the strength of the story, the frequently terrific acting, and a shrewd use of classic plot devices, the movie ages with dignity, like an old Bentley. But it takes a few particular actors and scenes to make Spartacus a living experience rather than just a grand exhibition piece. Top honors must go to Charles Laughton who plays his scheming, powerful yet goodhearted Roman senator as though it had been custom-made for him. It is a wonderful display of a kind of larger than life performance that would fall out of fashion a few years later, and has never really returned. Laughton turns his Gracchus into a vividly alive and generous Falstaff kind of man, while on another level he is a survivor among the backstabbers in Rome and undoubtedly one with blood on his hands. Yet this exquisite package isn't all that the viewer perceives, because Laughton's presence carries just enough of a hint of irony, like a quick wink of the eye, to remind you and the crew and probably himself too, that this is all theatre. This meta-comment is effective for several reasons, the simplest one being that it is true, it is all theatre and the audience is granted the intelligence to share this consensual hallucination with Laughton and Olivier and the other great actors. Furthermore, the setting of the senate in Rome resembles a stage where political monologues and dialogues determine the nation's future, and the scenes in this milieu, strongly dominated by Laughton, emerge as a kind of play-within-play in Shakespeare's manner. This observation suggests another undercurrent to Laughton's multilayered presence; the enormous tradition of stage productions set in the classic Rome of Spartacus, leading by way of Shakespeare's Julius Ceasar all the way back to the playwrights and rhetoric masters of the ancient high culture. In addition to bringing to life his admirably vivacious Gracchus, Laughton's subtle meta-performance reminds us of the extraordinary context, even in a commercial Hollywood movie, of a Roman stage. Of course, Laurence Olivier and Peter Ustinov hold their own ground as thespians; Olivier's complex, ambivalent Crassus bringing much of the same Shakespearean nutrition to the table as Laughton, while the younger Ustinov represents a slightly more naturalistic and less formalized kind of acting. The scenes between Laughton and Ustinov are not only wondrously entertaining, but also make for a passing of the torch, to some extent. The American actors can't help but suffering in the Anglofied tone of the movie, and there is an awkward clash between traditions at times, such as Olivier and his brother in law (Broadway actor John Dall) who seem to be in separate movies. Kirk Douglas, whose movie it after all is, does a good job in emphasizing the physical aspects of his Spartacus; a commanding example of the hero in his most visceral incarnation. With this choice comes a natural lack of insight behind the righteous warrior mask of Spartacus, whose entire emotional life is distilled down to his love for Varinia (a very beautiful Jean Simmons). The hero archetype rests comfortably on Douglas' broad shoulders, but it also shifts the thematic bias away from the notion of the 'rebel' to that of the 'warrior', and turns Spartacus into more of a war movie than it maybe should have been. Compared with Ridley Scott's Gladiator, Spartacus finds a presumed rebel becoming a field general, while Gladiator finds a field general becoming a rebel. The later movie gains in emotional pull from this characterization of the hero role. Kubrick may not have left too strong a mark on this movie, except for its general excellence, but the memorable final scene stands out enough that it hints of the unique ideation of the great director. As the crucificed hero suffers on the cross, his wife and new-born child stand by and silently weep, unable to reveal their identity. It's a heavy, archetypal scene, if not outright psychedelic then certainly Jungian, and it is a fitting apex to a closing reel that also saw Olivier and Douglas finally meet in a scene which brilliantly contrasts two types of power--that of the office and law, with that of nature and the common man. While the overall bias towards a gung-ho war movie reduces the movie of its potential multi-layered quality, there are enough moments of depth and ambivalence to satisfy the psychedelic mind, and the closing scene in particular is almost Dali-esque. A final thought: Kubrick does well in exploting the studio resources and huge number of extras at his hands, and creates a movie that truly looks expensive, even today. At the same time, many of the sets still look like studio back-lot creations in a manner typical of older Hollywood movies, and it's unfortunate that not more filming took place in actual outdoors settings. This effect is compounded by a curious presentation of Southern Italy as about the same size as your local neighborhood, so that slaves on the run keep bumping into one another in the most unlikely fashion. These two drawbacks are perhaps the strongest reminders that the movie belongs to a much earlier era and different audience attitude than Scott's Gladiator. NOTE: the reinstated scenes featuring a subtle (or not so subtle) homosexual undertone between Olivier and young Tony Curtis are quite worthwhile and contribute to the modern and more ambiguous aspect of Spartacus. The sequence is slightly inferior technically and you can tell where it begins and ends, but it nevertheless is a vital addition to the film. Anthony Hopkins was apparently hired to imitate Olivier's voice as the original soundtrack had been lost, while Curtis was still around and redid himself.

Posted by Patrick at Lysergia

at 12:49 AM MEST

Updated: 10 August 2013 12:41 AM MEST

2 April 2013

Sherlock Holmes (2009)

Topic: S

I didn't get to see Sherlock Holmes until now, but its rather favorable reception upon release had me curious, along with the surprising casting choices. It marks Guy ‘Snatch’ Ritchie's return to A-list movies after a long slump that involved serial career-killer Madonna among other things. Ritchie's direction here is full of self-confidence, although some might feel that the Tarantino school of kinetic action and playful meta-cinema is getting old. I wanted to like this movie, and for the first 15 minutes or so, I felt that its bold take on the Sherlock Holmes mythology worked well. But then, just like with Prometheus, false notes began to appear here and there, and they seemed to grow louder with each re-occurrence. Casting a very American method actor like Robert Downey in a role whose outward appearance has been defined by the artistocratic features of Basil Rathbone and Jeremy Brett is a daring choice that borders on the bizarre but, again, for a while it seemed to work. Downey has earned a reputation of being a very gifted actor, and even when he's in deep water he remains watchable. But his take on the role seems almost like an understudy variant of his 'Tony Stark' (Iron Man) character. He expresses at least two different simultaneous emotions in every shot, which is useful in psychological dramas or to inject depth into airhead Marvel movies, but is not something you would link with Victorian Britain and its ritualized use of outward control and the stiff upper lip, nor does it conform in any way to the way Sherlock Holmes has been portrayed in the past, least of all in Conan Doyle's stories. It is billed as a Sherlock Holmes movie, and makes extensive use of details from the Holmes myth, but neither the protagonist nor the basic plot bear much resemblance to the stories that made Holmes world famous. To begin with, there should be a distinct crime and an associated mystery, which form the riddle for Holmes' logic to disentangle. Everything else should be secondary to the carefully constructed problem which the great detective is to solve with his deductive reasoning. This movie isnt't like that; it's more like a Jason Bourne film set in 1890 London. Some of this is clearly on the director's wishes, but too much of the most recognizable elements of Holmes are sacrificed. The jarring feeling is amplified by a narrative that confuses intelligence with arcane knowledge, as if Holmes was in line for a sequel to The Da Vinci Code. Deductive logic, the type of intelligence championed by Doyle and incarnated in Holmes, is hardly ever put on display in the film. The type of audience participation that comes with classic murder puzzles, where the reader/viewer can try to match his wits with the detective is made near-impossible by the confused, uncomprehending way Ritchie & co deals with Holmes’ methods of logic and objectivity. Instead of delighting in the man’s brain power, we are treated to a number of overlong fistfights and slow-motion explosions that seem targetted at a bonehead audience who liked Ritchie’s Brit gangster flicks for the wrong reasons, and have never heard of Conan Doyle. At its worst, Sherlock Holmes feels as if someone who owned the movie rights to the character name used it to cash in by making a movie that drew on several recent successes and whose hero just happens to be named Sherlock Holmes. It is so removed from the Holmes universe that the hero and film could have claimed to be 100% original and named something else, 'Reginald Clark, Victorian Superhero' or whatever, but of course many more people will go to see a 'Sherlock Holmes' movie. I wasn't particularly impressed with the script; the plot was overwraught and its fake magic too similar to recent successes The Prestige and The Illusionist. It is historically accurate to depict magick activity within English society during the fin de siecle era; the problem is that this theme of magick rarely or maybe even never entered Doyle's Sherlock Holmes canon. So even in its subject matter, the movie manages to distance itself from the canonical source. The classic Holmes stories are often eerie and ghostly, but this is due to the seemingly inexplicable mystery that Holmes is to solve, combined with a clever use of gothic or exotic details. 'The Sign Of Four' is masterful in this respect, and the fine TV series with Jeremy Brett captured this eerie suspense well. This movie, however, is not about creepy atmospheres and spooky details; it's loud and brash whereever it goes. For someone like me, who grew up with Doyle's stories, this film is more an insult than anything else; Downey's drastic reinterpretation of the role is one thing, but the scripts' attempts to replace deductive intelligence with obscure knowledge lacks all justification. On the upside, Jude Law seems comfortable with his rather young Dr Watson, and he goes some way to keep the movie on an identifiable stylistic track. Rachel MacAdam is pretty and likable, but hardly ideally cast for an international jewel thief, with her high school girl demeanor. Mark Strong is good as the main villain, and the minor roles are generally well executed. Except for some mediocre CGI, Victorian London is convincingly rebuilt and the movie makes excellent use of both muddy streets and landmarks new (London Bridge is shown under construction) and old. Similarly the costume work is impressive, offering lots of variation in fabric, patterns and styles, despite the supposed uniform dress codes of the era. The clothes look used and worn, for an additional nice detail. The only dubious note is a bizarre Gary Numan-like jacket worn by 'Dr Watson' in a restaurant scene. This movie clearly works better for those unfamiliar with the classic Sherlock Holmes universe, which it has little in common with. But the plot is too clichéd and comic book-like to turn this into a period action story that truly works, and the viewer is left with a movie that has all its best elements in the periphery, while its core is insufficiently thought-out and unsteadily built. I'm not sure why Sherlock Holmes was so enthusiastically received, but I suspect it rode on the trend of comic superhero movies, an angle which Robert Downey's presence and performance amplifies. 6/10

Posted by Patrick at Lysergia

at 12:17 AM MEST

Updated: 10 August 2013 12:34 AM MEST

Newer | Latest | Older

|

In accordance with the title there is a strong focus on eyes, in various symbolic and physical representations. Gary Sinise's sinister military officer turns the metaphorical 'snake eyes' of the title into an actual facial aspect, becoming less human and more cold and deviously reptile as the movie progresses. Perhaps this ocular theme justified use of POV flashback sequences (some which are actually 'false') that occur three times, but they are largely unsuccessful and distracts the viewer by inserting new dimensions to little effect. In typical BDP fashion the inspired creativity goes one step too far, but its more of an annoyance than truly damaging.

In accordance with the title there is a strong focus on eyes, in various symbolic and physical representations. Gary Sinise's sinister military officer turns the metaphorical 'snake eyes' of the title into an actual facial aspect, becoming less human and more cold and deviously reptile as the movie progresses. Perhaps this ocular theme justified use of POV flashback sequences (some which are actually 'false') that occur three times, but they are largely unsuccessful and distracts the viewer by inserting new dimensions to little effect. In typical BDP fashion the inspired creativity goes one step too far, but its more of an annoyance than truly damaging.