GRANMA INTERNATIONAL 1998. ELECTRONIC EDITION.

Havana, Cuba

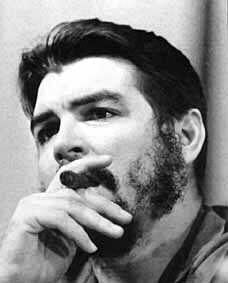

CHE THE

COMMUNICATOR

A

death

threat |

|

BY GABRIEL MOLINA

A deathly silence invaded

Prensa Latina's spacious newspaper office that morning in 1959, when the door to the

editor's office opened and a voice was heard over the habitual noise:

"Molina, I'm going to kill you!"

It was the voice of Che Guevara, who entered followed by Masetti...

Brilliant multifaceted and single-faceted figures have always existed

and always will, but few have been as versatile and apparently contradictory as Che: he

was a doctor and an economist, a researcher and a guerrilla commander, a political leader

and a diplomat, a practical man and a theorist, a poet and a mathematician, an athlete and

a thinker, and even a photographer and a journalist.

It is a fact that he was a professional in everything, because he really

undertook everything with an "artist's delight."

His first and more professional contact with the press was in Mexico,

when he worked as a photographer for the Agencia Latina, based in Buenos Aires during the

Peronist period. That Latin Americanist dream obsessed him all his life. It could be said

that he realized it in Cuba with Prensa Latina.

Destiny had it that the few journalists and very few Latin Americans who

were able to go to the Sierra Maestra to do stories on the Rebel Army included another

dreamer by the name of Jorge Ricardo Masetti. I said to write an article, because

fortunately there were more reporters serving as soldiers in the Sierra Maestra - and in

the cities and plains - than those who could get up there exclusively as journalists. Che

himself was a journalist there, with the daily El Cubano Libre and Radio Rebelde, both of

which he founded.

Fidel, Che and Masetti organized the news agency Prensa Latina S.A.,

whose first editor, logically, was Masetti. Its president was a Mexican entrepreneur, and

its greatest inspiration, although he didn't figure in any way, was Che Guevara, who often

visited the agency. He spent many hours talking with Masetti, among other things, on what

was happening in the press and the agency's progress. He knew the correspondents or those

aspiring to be correspondents.

Apart from that, Che was an excellent feature writer. The first and

best-known work on the Sierra Maestra was his book Guerra de Guerrillas (Guerrilla

Warfare). And in those early years of the Revolution, his articles in Verde Olivo, under

the pseudonym "El Francotirador" (The Sharpshooter), were frequent. Along with

many labors he undertook simultaneously, he was instruction head of the Rebel Army and, in

this capacity, worked directly with the magazine. He also wrote for the daily Combate,

organ of the Revolutionary Directorate, and for Hoy, the Popular Socialist Party

newspaper.

In spite of his aura of a difficult, inaccessible personality, many

journalists can testify that among the revolutionary leaders, he was surpassed only by

Fidel in terms of attention; in his own style, like when he made us participate in

productive work before giving us information.

I personally recall with deep pleasure that the first really significant

interview I did after the triumph of the Revolution was precisely with Che in his office

in La Cabaña (the old fort housing the Rebel Army). I had met him a few days previously,

when I visited him with Commander Guillermo Jiménez, assistant editor of Combate, and it

was Che who introduced us to Rogelio Acevedo, the then beardless, long-haired captain.

It's a fact that one was predisposed in favor of Che. And that feeling, far from being

deceptive at close quarters, was impressive.

When right-wing elements attempted to suppress the daily Combate which,

unexpectedly, demonstrated a clear left-wing position - far more so than Revolution,

edited by Carlos Franqui - we informed him that they didn't want to use Combate for state

advertising. Che called Guillermo Jiménez, René Anillo and myself into his office at

midnight, at the National Institute of Agrarian Reform (INRA), which Che also headed, and

we talked there for a long time.

A few days later, the boycott of Combate ended, which gave faith to the extent of his

attentiveness.

I understood that from the day on which he left me cold, threatening to

shoot me down in the spacious Prensa Latina newspaper office, which is a story I've never

told before.

I was facing him and all the journalists waited expectantly. I got up and moved towards

him, asking him why he wanted to do that.

Che Guevara also advanced towards me. I felt the tension increase in the

air when he answered, seemingly angrily: "Because of what you published in

Combate!"

Still going towards him, I asked if I'd written something untrue or inaccurate.

"No. It was accurate. But you put a really big headline on the front page."

"Didn't it deserve it?" he asked.

By this time, we were face-to-face, almost touching. Then he lowered his

voice so that the others wouldn't hear and said to me, smiling and placing his hand on my

shoulder:

"The thing is, I said things that the Fidel thinks but can't say. And somebody could

believe that I think differently than he does."

After that episode, I smiled to myself when the "outside" press stated that Che

had left Cuba because of discrepancies with Fidel.

That unity with Fidel in terms of thought and action is eternal

and warranted me a "death threat." |