. Claiming

that it is wildly inaccurate, and borrows details of her life that she had disclosed to Golden over the course of a week's worth of interviews, she has even threatened to sue. According to Allison's paper, Iwasaki thinks of the book as "a 'potboiler' where geisha appear as prostitutes-more a fantasy of Western men than an accurate representation of Japanese geisha."

Told through the grey eyes of a fictional geisha,

through the grey eyes of a fictional geisha, Memoirs also presents a challenge to those intent on dismantling dominant Western images of Japan. ("Mount Fuji, cherry blossoms, samurai, and geisha," groans Bardsley.) Sayuri's light-colored eyes stand as an apt metaphor for the book itself. Presented as Eastern-"too much water" says a fortune-teller-and Western in color, Sayuri's eyes are as much a manufactured hybrid as the book, all fairy tale and "ethnography," fantasy too often mistaken for reality. Ultimately, Sayuri's eyes are a dead giveaway of the man pulling the strings-they reveal her as nothing more than a white man in geishaface.

SEXING UP THE GEISHA

Is it better or different

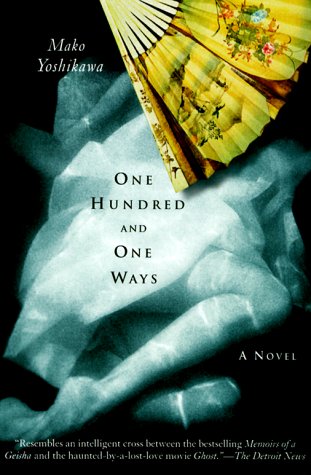

when a Japanese American woman-the great-granddaughter of a geisha, the author bio informs us-tries on the identity of a geisha? I was certainly hoping so. Mako Yoshikawa's One Hundred and One Ways seemed promising. Kiki Takahashi, the Japanese American narrator, tells the stories of her mother and grandmother-the mother who eloped with a man to America, only to be abused and abandoned, and the grandmother who suffered through her geisha training and earned great love.

Is it better or different

when a Japanese American woman-the great-granddaughter of a geisha, the author bio informs us-tries on the identity of a geisha? I was certainly hoping so. Mako Yoshikawa's One Hundred and One Ways seemed promising. Kiki Takahashi, the Japanese American narrator, tells the stories of her mother and grandmother-the mother who eloped with a man to America, only to be abused and abandoned, and the grandmother who suffered through her geisha training and earned great love.

Kiki herself is haunted, quite literally, by the ghost of her beloved friend Philip. After reading the back of the book I thought, "Hey, a Japanese American author writing about a Japanese American woman with a geisha as a grandmother. Maybe she'll find a way to reclaim the image from the realm of stereotype."

Kiki herself is haunted, quite literally, by the ghost of her beloved friend Philip. After reading the back of the book I thought, "Hey, a Japanese American author writing about a Japanese American woman with a geisha as a grandmother. Maybe she'll find a way to reclaim the image from the realm of stereotype."

It didn't quite turn out that way,

and I should have known that from the first paragraph. As Kiki pulls on her clothes, she says, "I dress at a leisurely pace, pulling my underpants up and sliding into them with a swivel of the hips, snapping on a bra with all the strut and reluctance of a striptease. I may have spent most of my life in New Jersey, but the blood of a geisha courses through me yet." From the start, Kiki buys into the Western stereotype of geisha as whore, and recreates herself in that mold, making us (me, at least) an unwilling co-conspirator and voyeur.

But although Kiki

seems to be quite fond of thinking of herself as a sexy geisha, she doesn't like it if anyone else does. She accuses her nice Jewish lawyer boyfriend Eric, "Are you sure you don't have an Asian-woman fetish?" after he asks if he can call her by her Japanese name, Yukiko, also the name of her geisha grandmother. The second chapter begins with a racial epithet that a drunk white man had accosted her with at a party:

|

|

|

|

|

The Author

Noy Thrupkaew

Noy Thrupkaew is the former associate editor of Sojourner: The Women's Forum, a 25-year-old national feminist publication. She writes frequently on international women's human rights, welfare policy, prison issues, and Asian and Asian American literature and film.

In September 2001, she will participate in a fellowship at The American Prospect in Washington, DC.

|

|

"The slit between an Oriental girl's legs

is as deliciously slanted as her eyes. Or so the saying goes, according to one man who never did find his way to my bed." With this statement, Kiki's sexuality as a Japanese American woman becomes both a point of vulnerability, and the site of revenge and power through the denial of sex. But instead of providing insight into the matter, she just turns herself into another stereotype-the sexualized lotus blossom victim and the emasculating dragon-lady sexual temptress all in one.

Kiki describes geisha

in the same contradictory ways. "In Japan and even America," she declares, "the word 'geisha' casts a spell of enchantment, conjuring the apparition of a beautiful woman, demure, docile, highly sexed and, most of all, always available." Her next statement links this image to how she believes she is claimed, perceived by white men as an Asian American woman:

What my grandmother

was to her customers, so, too, am I to a significant number of American men, Eric among them: the repository of wiles, feminine and erotic, one hundred and one of them. . . . what a geisha is to Japan, a Japanese woman is to America.

But instead of rejecting

the geisha projection, Kiki is strangely drawn to it, and exploits the sexual cachet of its imagery for all it's worth. Thinking of her sexual blossoming in college when she changed her name from Yukiko to Kiki, dropped some weight, and "went out" with nearly every member of the tennis team at Princeton, Kiki says, "it was not until I became Kiki that I was able to adopt out of choice the life that [Yukiko] was forced into living." Between accusing Eric of being a rice king and declaring herself an Asian sexpot, Kiki alternately rebels against and embraces this image of geisha as exotic slut, but refuses to be anything more than just contrary. Instead of a character who grapples with whether degrading images can be reclaimed and made into a powerful identity, or challenges her own notions about her sexuality and ethnicity, we get a reactive Me So Horny stripshow that spanks us for looking.

Perhaps Kiki would have less

of a hard time with the yellow fever thing if she would even consider dating a few men of color, or associate with people who look like her:

. . . two Asian women around my age stop talking to look at me. They had been speaking in what sounded like Japanese. They covertly glance at me with tacit recognition and as usual, I turn away without acknowledging our kinship. Like my college roommates and my adult lovers, my childhood friends were white. Still, it usually seemed that no matter how hard I tried to disassociate myself from other Asians, we were all inevitably linked together in everybody else's mind.

*

Part 4 *

Part 5 *

Part 1 *

Part 2 *

Any questions regarding the content, contact Asian American Artistry

site design by Asian American Artistry

Copyright © 1996-2003 - Asian American Artistry - All Rights Reserved.