David Johnson/ The Gazette

Thursday, June 15, 2000

When the local shareholders of the Expos recruited New York art-dealer Jeffrey Loria last fall to become the franchise's new managing general partner, they expected him to preside over construction of a new downtown stadium.

Just in case Loria got cold feet about the stadium, the local partners had him agree to take a 3-per-cent equity penalty if the stadium project fell apart "solely as a result of" Loria failing to inject $57 million into the club's recapitalization drive.

After all, the purpose of the recapitalization (Loria's $57 million plus $72 million from new local investors) was to help build a new stadium, pay off operating debt, and cover costs until a new facility opened.

The penalty provision is contained in the partnership agreement the two sides signed last December, a copy of which has been obtained by The Gazette. But Loria, who owns 24 per cent of the Expos, needn't worry about it. His proposal to scrap the $200-million stadium plan he and his partners had agreed upon, and spend an extra $70 million for some sort of retractable roof, means it's currently the local owners who have cold feet.

As a result, nobody is putting up the money they pledged, and that's not good news for the stadium project. The team's owners have to come up with $100 million in stadium money before the Quebec government will agree to pay interest on a loan for another $100 million. The recapitalization was to provide $50 million toward the new park, the owners' other half was to come from the sale of seat licenses.

In recent months, Quebec pharmacy mogul Jean Coutu, one of the three new local investors, has been lobbying his fellow local shareholders to delay construction until Major League Baseball signs a new collective bargaining agreement with its players' association. It makes no sense, Coutu has been arguing, to commit millions of dollars to a new facility while there's the threat of a long lockout or strike.

The players' collective agreement ends this year, but the players' association is expected to exercise its option to extend it one year. Many analysts are predicting a long labour disruption after the 2001 season.

Coutu is emerging as a key figure in the Expos' internal machinations - and in the court of public opinion. Twice in the past six weeks, he has told reporters on the record that no downtown stadium should be built before a new collective agreement is signed. He is well-liked by his Quebec partners, and a poll published last week showed the public regards him as the second most trustworthy spokesman on the Expos file, after club co-chairman Jacques Menard. Nobody else is even close.

Everyone agrees a new stadium would revive sagging attendance for the Expos, as has been the case with new stadiums in other cities. But most analysts think that without improved revenue sharing, without baseball forcing large-market teams to share their local cable-TV revenues with small-market teams, a new stadium alone wouldn't generate enough new revenues to prevent their best players from signing with rich teams as free agents.

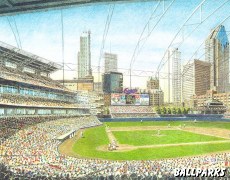

But there's no doubt, they say, that it would be more fun watching baseball in a pretty, open-air downtown stadium than in the dreary, closed-roof Big O in the East End.

"My feeling has always been that a new stadium, situated downtown, can be successful if Montrealers can be convinced that baseball is here to stay," said Francois Richer, a professor of accounting at the Ecole des Hautes Etudes Commerciales.

"A lot of my friends go to Alouettes games and they wouldn't watch a football game on TV if their lives depended on it. They don't know the name of one player. But they go there for the party, for the fun of the show. With the Expos, there's nothing interesting in the Olympic Stadium if you're not a baseball fan."

Moving to downtown Molson Stadium from the Olympic Stadium did wonders for the Alouettes. Because of a scheduling conflict that had booked the rock band U2 into the Big O on Nov. 2, 1997, the Alouettes played a playoff game that day at Molson Stadium, where they hadn't played since the 1960s. The game sold out - and the Als stayed there.

In 1997, the Als averaged 6,000 fans in the Olympic Stadium and had 1,800 season-ticket holders, according to Richard Blais, the club's vice-president (marketing). In 1998 at Molson Stadium, they averaged 13,000 and had 6,000 season-ticket holders. Last year, they averaged 19,200 and had 10,000 season-ticket holders. This year, they expect every game will be sold out to the 19,461 seating capacity, and they have 15,000 season-ticket holders.

At Olympic Stadium, 85 per cent of fans were francophone and 15 per cent non-francophone, according to team president Larry Smith. Now, the mix is 65/35, reflecting perfectly the city's metropolitan breakdown.

When Brochu unveiled his original plan for a $250-million stadium three years ago this week, he made public some polling numbers showing 78 per cent of fans at the average Expos game in the Big O were francophone, 11 per cent local non-francophones, and 11 per cent tourists.

Build it, and the English will come? And the Greeks and the Italians? Not to mention more francophones? That's what the Alouettes' experience suggests. Then again, maybe not enough would come.

Whatever the result, the partnership agreement between Loria and the local shareholders contains a "shotgun clause," to take effect five years after the opening of any new stadium. The clause would allow one party to demand a buyout from the other. If the other party refuses, then that other party must automatically agree to a buyout itself.

"It's basically: 'You buy me, or I buy you,' " said Guy Lachapelle, an expert in corporate law at the Centre for the Study of Regulated Industries, affiliated with the McGill University faculty of law.

Previous Story

Next Story

Head back to Save the Expos Home Page