By Paul Cherry

A firm deciding whether the Expos proposed downtown ball park meets major-league standards also has been helping the team complete its stadium plans.

In the past week, Kansas City-based HOK Sports Facilities Group has quietly met with representatives of the ownership group angling for control of the Expos and Axor Group Inc., the Montreal company chosen to design and build the proposed downtown ball park. HOK took ownership group representatives and Axor officials on a tour of baseball stadiums in the U.S. last week to discuss design.

"I can't say what ball parks they were, but they are comparable to what our plans call for," said Jean Simard, an ownership-group spokesman, adding that no similar trips are planned for this week.

This has transpired while Montreal sports-radio phone-in shows and media commentators have wondered aloud if HOK Sports is in a conflict of interest. Can a U.S. company that designs spectacular, yet expensive ball parks make an unbiased decision on a very inexpensive Montreal downtown- stadium proposal? And does the stadium's $175-million Canadian price tag mean Expos fans will be getting shortchanged?

None of three spokesmen for the Expos' proposed ownership group interviewed last week called HOK's invovlvement in stadium approval an unfair situation.

But what is this company that holds the Expos' fate in its hands?

Major League Baseball is a monopoly, so it's not surprising that a company that works closely with it - HOK Sports - almost has a monopoly on stadium design. HOK has been involved in the design of 28 of the National Football League's 30 stadiums. It's designed almost every new baseball stadium built since it worked on the new Comiskey Park in Chicago in 1991. It designed the highly regarded Camden Yards for the Baltimore Orioles and will design the new Fenway Park in Boston.

The company refused requests for interviews for this article, citing baseball's strict confidentiality clampdown on ownership matters. The stadium is a crucial part of the plan to bring in New York art dealer Jeffrey Loria as a $75-million Expos investor and the team's new general managing partner. The approval process has hardly been a one-way street. Roger Samson, a marketing consultant for the team, said HOK and Axor have had several meetings recently, including an important one last Wednesday to go over design questions.

Experts on baseball economics doubt HOK would play politics with its assignment from Major League Baseball commissioner Bud Selig.

"If you bring someone in to tell you what can be done, they are at least one of the companies that you would ask," said Ken Shopshire, author of The Sports Franchise Game and a professor at the Wharton School of Business in Philadelphia.

HOK specializes in designing revenue-generating ball parks where people can expect to see more than just a game. It has designed parks that include elaborate restaurants and bars or theme parks engineered to bring out more families.

Those extras are crucial in allowing small-market teams to pay escalating salaries and field a competitive team.

The question now seems to be less about whether the Expos can build a stadium for $175 million Canadian than whether such a facility would help the Expos pay players like outfielder Vladimir Guerrero five years from now, when he seeks a new contract.

"It would be the least expensive facility built in the last dozen years. It could be possible to build it, but I wouldn't guarantee it," said Mark Rosentraub, a professor at Indiana University who recently published a study called Major League Losers, which examines public financing of stadiums.

"If you don't count land and you don't count soft costs - if they say construction costs alone are $175 million - it is not impossible. But if you include infrastructure and other remediation É generally required around these facilities, then that is different.

"Here is the critical question: are we going to have a facility that generates the revenue to make the Expos competitive, or are we going to put them in the $175-million stadium and not make any money? The problem Montreal has to solve is that it has to make enough revenue to get the players it wants."

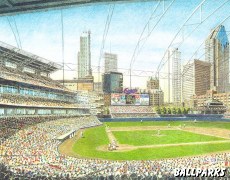

Expos president Claude Brochu, who would leave if baseball approves of the new ownership group and its business plan, proposed two years ago that the team build a $250-million, 37,000-seat park with an ornate brick exterior, natural grass, a retractable roof, 60 corporate loges and heated stands. The design also included a 300-seat VIP restaurant plus a 150,000-square-foot terrace in right field for activities and entertainment designed to keep fans and their money around before and after games.

Among the few facts that are public knowledge about the new design are: the ornate brick exterior is gone, or at least extensively modified; the retractable roof is gone; and the stadium would seat somewhere around 35,000. There's no word yet on extras that might boost revenues.

Minority owner Mark Routtenberg refers to the design as "fan-friendly" and said the club doesn't believe the simple, utopian idea of "build it and they will come."

"We have plans and are looking at many ways that will give the fans a reason to come out to the ball park," Routtenberg said last week.

But Montreal fans are looking at the price tags of recent parks and the proposed cost of those set to open early in the next millennium, particularly in markets similar to Montreal:

n The Milwaukee Brewers' Miller Park is still under construction. In 1998, its cost was estimated at $250 million, financed mostly by a regional sales tax. It is set to open by April 2000. HOK did not design the stadium, but was runner-up to a Dallas company that impressed Brewers owners with its plans for a retractable roof.

The Minnesota Twins and the city of Saint Paul agreed this month to build a $325-million riverfront ball park. Stadium construction costs alone would not exceed $277 million. The project is also dependent on an ownership change.

Samson says comparing the Expos' project to what is going on in the U.S. is vulgar price-tagging.

"We don't want people to think we are building a diminished or scaled-down version of a real stadium," Samson said recently.

Construction costs for the ball park are cheap because of the relative lull in Montreal's construction industry, he said.

"That has an impact on price, there is no question about it, and it's a substantial one," Samson said.

He might have a point. Most people guilty of price-tag envy look to the Seattle Mariners' new Safeco Field, which opened last month with a retractable roof and a $517-million cost. That includes $100 million in cost overruns.

But Seattle's in a construction boom - which drives up demand for labour and equipment - fueled by the U.S.'s thriving economy and the city's flourishing high-tech sector. Since 1995, an estimated $12 billion Canadian in construction permits were awarded.

By comparison, Montreal's Economic and Urban Development Department estimates the value of building permits issued since 1995 at about $2.3 billion (Canadian). However, the value of permits rose significantly in 1998 and during the first six months of '99.

Samson also said money will be saved by having the same firm design the ball park and build it.

The ownership group approached contractors and asked for a price before they start designing the building in detail.

"That's an approach that is a highly effective way to make buildings, which is not a common or traditional approach," he said. "The reason we are so comfortable with it is we have people here that have done it before with buildings in Montreal, including the (Jarry Park tennis stadium). I don't think anybody would criticize the efficiency and functionality of that stadium.

"Axor's program has this advantage over the others. This is a project that lends more efficiency to us. These two reasons combined make it so we can build a stadium for much less than they're building in the States."

An official with the ATP tennis tour said the Jarry Park stadium, the only major sports venue built so far by Axor, is impressive, with good sight lines and not a bad seat in the building.

"Our strong point is design-build," said Axor's communications director Marie-Josee Gagnon. She described the concept as one in which costs are cut by eliminating the long process of going back and forth between designer and construction company.

"We integrate the design and the construction. The Expos stadium project is like that. In our company, we have people who orchestrate both. That also means the designers can make changes in the design as we go along that cut costs.

"That is the strength of design-build. You can guarantee a price. We have developed a control over costs."

Previous article

Next article

Head back to Save the Expos Home Page