Bronze Age `Trick or Treat'

A brief editorial treatise by Croesos the Classicist

At this point it is appropriate to say a few words about warfare during Mycenćan times, as the differences between Agamemnon's army and a modern military force are significant to a proper understanding of the Trojan War.

In the first place, neither side in the Trojan War should be mistaken for a single army, but rather they were each an alliance of several independent nations. On the one side were the Achćans, who were sometime referred to as Argives or Danaans. They are sometime referred to by later sources as `the Greeks', but this term was not in existence until several centuries after the Trojan War. This coalition was under the nominal leadership of Agamemnon, who was the king of the Achćans' most important city, Mycenć, and provided the most ships (one hundred) and men to the Argive forces. As a symbol of his preeminence over the other Achćan kings Agamemnon carried a scepter crafted by Hephćstos that had been given to his father Atreus.

Despite these credentials, Agamemnon's authority was never unquestioned. Each of the kings and princes who brought troops to the effort were extremely conscious of their standing within the hierarchy of the army. Any slight to their honor was regarded as a grievous assault on their character, and the offended Argive lord would often threaten to take his men and return home unless proper reparations were made.

The situation was much the same on the Trojan side. The Achćan invaders outnumbered the besieged residents of Troy by more than ten to one, but the Trojans supplemented their military strength by drawing aid from the numerous alliances Priam had formed over the years. Thus the "Trojan" army was composed of men from many different nations. However, unlike Agamemnon, Priam's age and unsurpassed wealth gave him a position of unquestioned respect and preeminence within his coalition, so the Trojans and their allies did not suffer from the squabbling and power struggles common among their opponents.

The importance of status was most likely due to the style of combat used by both sides. Unlike later Greeks, the participants in the Trojan War did not fight in tight, well ordered formations like phalanxes. This was an Heroic Age, and that meant fighting was done by individual heroes with a minimum of teamwork. The typical combat sequence goes something like this. A group of Argives and a group of Trojans encounter each other. The foot soldiers and lackeys clash and mix it up for a few minutes until their leaders can wade through to the front of the action. These two heroes will then battle it out, first with spears and, if that fails to settle the issue, closing with swords to finish off the matter. Eventually one of these two champions will either be killed or wounded so badly that he has to withdraw. When this happens the victor's followers gain heart and surge forward while the fallen hero's men turn and flee, screaming "run away, run away!"

This style of fighting resembles nothing so much as a pack of wolves. While loosely a group, the members of the pack engage the enemy individually and their prowess on the battlefield determines their status within their own pack. The reason that the various heroes on both sides were lords and kings was, in part, due to their superior battle acumen. Because of the carnage these godlike (and often god spawned) supermen were capable of wreaking on ordinary mortals they received the best foods and were equipped with the finest armor and weapons. If suddenly they can't "deliver the goods" by killing the enemy, their position of privilege comes under question. It is for this reason that questions of honor and status are so important for the various heroes on each side. The whole `pack dynamic' of both groups was geared towards achieving status, so naturally the heroes guarded their prerogatives jealously.

Although the heroes usually fought each other individually, there was a strong "buddy system" on both sides where two heroes were often found working together and guarding each others backs. Examples of such teams were Odysseus and Diomedes, the brothers Agamemnon and Menelaos, the two Aiases, Glaukos and Sarpedon, and, of course, Achilleus and Patroklos. Although there are certainly practical benefits involved in this system, there are also valuable literary reasons for it. It is much easier and less contrived to do exposition and character development in a dialogue than a series of monologues.

Another important consideration for the Achćan army was that of supplies. As the invaders, they didn't have the network of farmers and herdsmen to support and feed them that the Trojans had. Given the difficulties they had in navigating their ships across the Ćgean to Troy in the first place [see Chapters Eight through Ten], making regular "supply runs" back to their home cities was out of the question. So how did they support themselves for a ten year siege? Quite simply, they lived off the land.

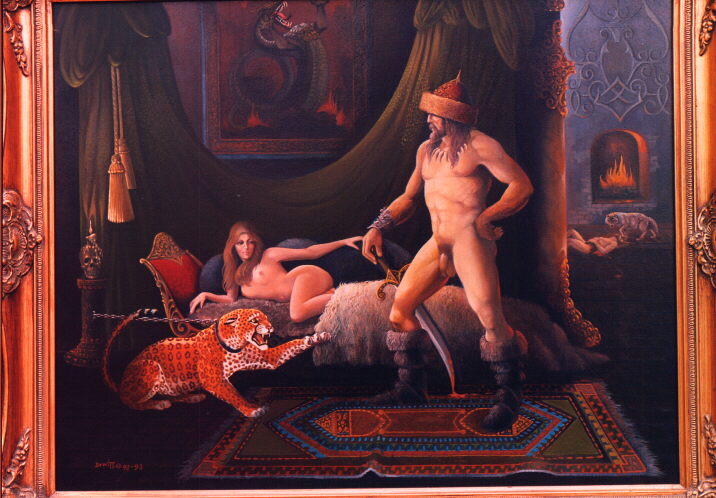

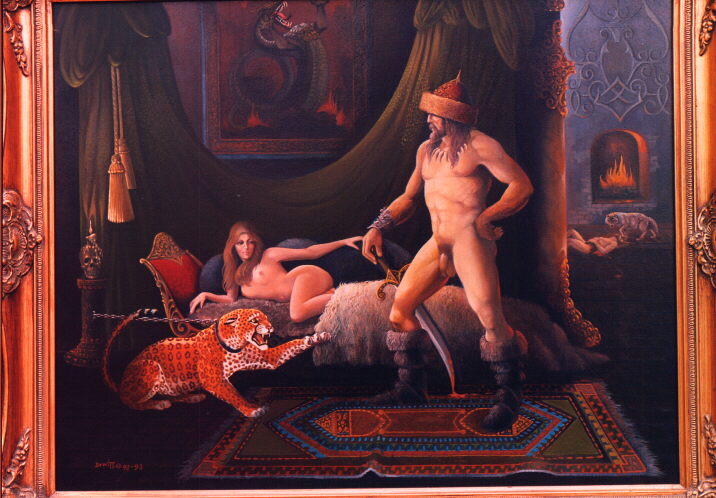

Most of the cities in the region were allied with Troy, so the Achćans considered them to be fair game. In fact, since most of these cities had much weaker defenses than Troy, which was surrounded by mighty walls built by the gods Apollo and Poseidon, they were tempting targets indeed. So whenever the Achćans started running low on supplies some of them would sail down the coast of Asia Minor, pick some likely looking prospect, and attack it. In all this we can clearly see a civilization in decline, where piracy and war are replacing farming and trade as accepted means of making a living. It was a more serious version of `Trick or Treat'. You'd dress up in your fiercest looking battle gear, hop ashore, and say, "I'm here. What have you got for me?" Sometimes it was a glittering treasure (treat) and sometimes it was well-manned fortifications (trick).