|

|

|

|

The Official

History of The Trail Where They Cried

Between 1790 and 1830

the population of Georgia increased six-fold. The western push of

the settlers created a problem. Georgians continued to take Native

American lands and force them into the frontier. By 1825 the Lower

Creek had been completely removed from the state under provisions of

the Treaty of Indian Springs. By 1827 the Creek were gone.

Cherokee had long called western Georgia home. The Cherokee

Nation continued in

their enchanted land until 1828. It was then

that the rumored gold, for which De Soto had relentlessly searched,

was discovered in the North Georgia mountains.

In his book

Don't Know Much About History, Kenneth C. Davis writes:

Hollywood has left the impression that the great Indian wars

came in the Old

West during the late 1800's, a period that many

think of simplistically as the

"cowboy and Indian" days. But in

fact that was a "mopping up" effort. By that

time the Indians

were nearly finished, their subjugation complete, their numbers

decimated. The killing, enslavement, and land theft had begun

with the arrival

of the Europeans. But it may have reached its

nadir when it became federal

policy under President (Andrew)

Jackson.

The Cherokees in 1828 were not nomadic savages. In

fact, they had assimilated many European-style customs, including

the wearing of gowns by Cherokee women. They

built roads,

schools and churches, had a system of representational government,

and were farmers and cattle ranchers. A Cherokee alphabet, the

"Talking Leaves" was

perfected by Sequoyah.

In 1830 the

Congress of the United States passed the "Indian Removal Act."

Although many Americans were against the act, most notably Tennessee

Congressman Davy Crockett, it passed anyway. President Jackson

quickly signed the bill into law. The Cherokees attempted to fight

removal legally by challenging the removal laws in the Supreme Court

and by establishing an independent Cherokee Nation. At first the

court seemed to rule against the Indians. In Cherokee Nation vs.

Georgia, the Court refused to hear a case extending Georgia's laws

on the Cherokee because they did not represent a sovereign nation.

In 1832, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in favor of the Cherokee on

the same issue in Worcester vs. Georgia. In this case Chief Justice

John Marshall ruled that the Cherokee Nation was sovereign, making

the removal laws invalid. The Cherokee would have to agree to

removal in a treaty. The treaty then would have to be ratified by

the Senate.

By 1835 the Cherokee were divided and

despondent. Most supported Principal

Chief John Ross, who fought

the encroachment of whites starting with the 1832

land lottery.

However, a minority less than 500 out of 17,000 Cherokee in North

Georgia) followed Major Ridge, his son John, and Elias Boudinot,

who advocated

removal. The Treaty of New Echota, signed by Ridge

and members of the Treaty

Party in 1835, gave Jackson the legal

document he needed to remove the First

Americans. Ratification

of the treaty by the United States Senate sealed the

fate of the

Cherokee. Among the few who spoke out against the ratification

were Daniel Webster and Henry Clay, but it passed by a single

vote. In 1838

the United States began the removal to Oklahoma,

fulfilling a promise the

government made to Georgia in 1802.

Ordered to move on the Cherokee, U. S.

General Wool resigned his

command in protest, delaying the action. His

replacement,

General Winfield Scott, arrived at New Echota on May 17, 1838 with

7000 men. Early that summer General Scott and the United States Army

began the

invasion of the Cherokee Nation.

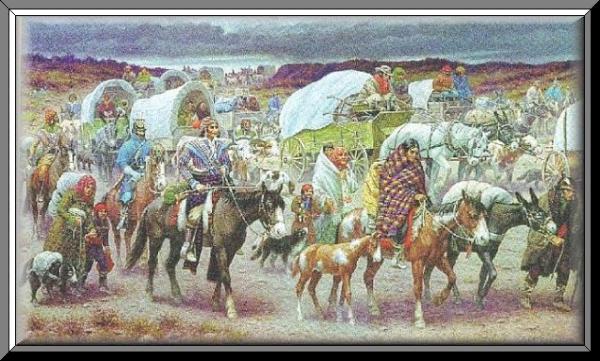

In one of the

saddest episodes of our brief history, men, women, and children

were taken from their land, herded into makeshift forts with

minimal facilities

and food, then forced to march a thousand

miles Some made part of the trip by boat in equally horrible

conditions). Under the generally indifferent army commanders,

human losses for the first groups of Cherokee removed were

extremely high. John

Ross made an urgent appeal to Scott,

requesting that the general let his people

lead the tribe west.

General Scott agreed. Ross organized the Cherokee into

smaller

groups and let them move separately through the wilderness so they

could

forage for food. Although the parties under Ross left in

early fall and arrived in

Oklahoma during the brutal winter of

1838-39, he significantly reduced the loss of life among his people.

About 4000 Cherokee died as a result of the removal. The route they

traversed and the journey itself became known as "The Trail of

Tears" or, as a direct translation from Cherokee, "The Trail Where

They Cried" ("Nunna daul Tsuny").

Ironically, just as the

Creeks had murdered Chief McIntosh for signing the Treaty of

Indian Springs, the Cherokee murdered Major Ridge, his son and

Elias Boudinot for

signing the Treaty of New Echota. Chief John

Ross, who valiantly resisted the forced

removal of the Cherokee,

lost his wife Quatie in the march. And so a country formed fifty

years earlier on the premise "...that all men are created equal, and

that they are

endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable

rights, among these the right to life , liberty and the pursuit of

happiness.." brutally closed the curtain on a culture that had done

no wrong.

Legend of the Cherokee

Rose (nu na hi du na tlo hi lu i)

When gold was found in

Georgia, the government forgot its treaties and drove the Cherokees

to Oklahoma. One fourth of them died on the journey west. When the

Trail of Tears started in 1838, the mothers of the Cherokee were

grieving and crying so much, they were unable to help their children

survive the journey. The elders prayed for a sign that would lift

the mother's spirits to give them strength. God, looking down from

heaven, decided to commemorate the brave Cherokees and so, as the

blood of the braves and the tears of the maidens dropped to the

ground, he turned them into stone in the shape of a Cherokee Rose.

The next day a beautiful rose began to grow where each of the

mother's tears fell. The rose is white for their tears; a gold

center represents the gold taken from Cherokee lands, and seven

leaves on each stem for the seven Cherokee clans. No better symbol

exists of the pain and suffering of the "Trail Where They Cried"

than the Cherokee Rose The wild Cherokee Rose grows along the route

of the Trail of Tears into eastern Oklahoma today.

The Legend of the

Cherokee Rose

More than 100 years

ago, the Cherokee people were driven from their home mountains when

the white men discovered gold in the mountains of Tears. Some of the

people came across Marengo County in West Alabama. It seems that

after they had left the mountains, they came this far south so not

have to climb more mountains. It was early summer and very hot, and

most of the time the people had to walk. Tempers were short and many

times the soldiers were more like animal drivers than guides for the

people. The men were so frustrated with the treatment of their women

and children, and the soldiers were so harsh and frustrated that bad

things often happened. When two men get angry they fight and once in

a while men were killed on the trip. Many people died of much

hardship. Much of the time the trip was hard and sad and the women

wept for losing their homes and their dignity. The old men knew that

they must do something to help the women not to lose their strength

in weeping. They knew the women would have to be very strong if they

were to help the children survive. So one night after they had made

camp along the Trail of Tears, the old men sitting around the dying

campfire called up to the Great One in Galunati (heaven) to help the

people in their trouble. They told Him that the people were

suffering and feared that the little ones would not survive to

rebuild the Cherokee Nation. The Great One said, "Yes, I have seen

the sorrows of the women and I can help them to keep their strength

to help the children. Tell the women in the morning to look back

where their tears have fallen to the ground. I will cause to grow

quickly a plant. They will see a little green plant at first with a

stem growing up. It will grow up and up and fall back down to touch

the ground where another stem will begin to grow. I’ll make the

plant grow so fast at first that by afternoon they’ll see a white

rose, a beautiful blossom with five petals. In the center of the

rose, I will put a pile of gold to remind them of the gold which the

white man wanted when his greed drove the Cherokee from their

ancestral home." The Great One said that the green leaves will have

seven leaflets, one for each of the seven clans of the Cherokee. The

plant will begin to spread out all over, a very strong plant, a

plant which will grow in large, strong clumps and it will take back

some of the land they had lost. It will have stickers on every stem

to protect it from anything that tries to move it away. The next

morning the old men told the women to look back for the sign from

the Great One. The women saw the plant beginning as a tiny shoot and

growing up and up until it spread out over the land. They watched as

a blossom formed, so beautiful they forgot to weep and they felt

beautiful and strong. By the afternoon they saw many white blossoms

as far as they could see. The women began to think about their

strength given them to bring up their children as the new Cherokee

Nation. They knew the plant marked the path of the brutal Trail of

Tears. The Cherokee women saw that the Cherokee Rose was strong

enough to take back much of the land of their

people. |

|

|

|

0, soft fills the dew, on the twilight

descending,

And night over the distant forest is bending,

And night over

the distant forest is bending,

Like the storm spirit, dark, o'er the tremulous main.

But midnight enshrouded my lone heart in its dwelling,

A tumult of woe in my bosom is swelling,

And a tear

unbefitting the warrior is telling,

That hope has abandoned the brave Cherokee.

Can a tree that is torn from its root by the fountain,

The pride of the valley; green, spreading and fair,

Can it

flourish, removed to the rock of the mountain,

Unwarmed by the sun and unwatered by care?

Though vesper be kind, her sweet dews in bestowing,

No life giving brook in its shadows is flowing,

And when the chill

winds of the desert are blowing,

So droops the transplanted and lone Cherokee.

Sacred graves of my sires, and I left you forever,

How melted my heart when I bade you adieu,

Shall joy light the

face of the Indian? Ah, never,

While memory sad has the power to renew.

As flies the fleet deer when the blood hound is started,

So fled winged hope from the poor broken hearted,

Oh, could she have

turned ere forever departing,

And beckoned with smiles to her sad Cherokee.

Is it the low wind through the wet willows rushing,

That fills with wild numbers my listening ear?

Or is it some hermit rill

in the solitude gushing,

The strange playing minstrel, whose music I hear?

'Tis the voice of my father, slow, solemnly stealing,

I see his dim form by yon meteor, kneeling,

To the God of the

White Man, the Christian, appealing,

He prays for the foe of the dark Cherokee.

Great Spirit of Good, whose abode is in Heaven,

Whose wampum of peace is the bow in the sky,

Wilt thou give to the

wants of the clamorous ravens,

Yet turn a deaf ear to my piteous cry?

O'er the ruins of home, o'er my heart's desolation,

No more salt thou hear my unblest lamentation,

For death's

dark encounter, I make preparation,

He hears the last groan of the wild

Cherokee.

By John Howard

Payne, author of Home, Sweet

Home. |

|

![]()

![]()