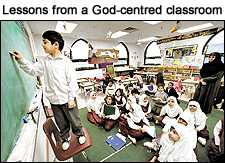

Sunday Special A little girl races to the school washroom, pauses at the door, says a prayer and darts in. A Grade 2 class setting out for the Ontario Science Centre recites a prayer before boarding the bus. A Grade 5 pupil stands at a microphone and calls the entire school to afternoon prayer in the gym where carpets have been rolled out in orderly rows. And in a science class, girls sitting on one side, boys on the other, a lesson on the solar system begins with a verse from the Qur'an.In the 18 Islamic schools in the Toronto area, prayer frames every action and infuses every lesson.

RON BULL/TORONTO STAR Religious education is so prized by

Toronto's growing Muslim community that there are not enough schools to

meet the demand. The first Islamic

religious schools opened in Ontario in the early 80s. There are now 25, as

parents who hold traditional values clamour not only for prayer but for

what some call the cocoon of safety their children will find in an Islamic

environment. Girls wear the Islamic head scarf, the

hijab, and pinafores or trousers, or sometimes both. Boys are in white

shirts and dark trousers. Their teachers are addressed as brother or

sister. The Ontario Ministry of Education reported

2,240 children in Islamic schools in 1999, but estimates from the Muslim

community suggest greater numbers, as many as 4,000. New

schools open every year. A high school is under construction in

Mississauga on the property of the Islamic Centre of Canada at South

Sheridan Way. The Taric Islamic Centre has applied to

lease an unused public school in North York and hopes to open for grades 1

to 4 in September. ``We want to teach more discipline, ethics and morality

which we feel is lacking in the public system,'' says board chair Haroon

Salamat. ``In trying to accommodate everybody, we feel the public board

has gone overboard.'' Even with new schools being added, there

are waiting lists. At the Islamic Foundation School in Scarborough, babies

are registered for junior kindergarten within a few days of birth. The

school opened with 38 children in 1993 and is at capacity with 300

students from grades 1 to 8. There's a waiting list of 650 for the next

three years. The Al-Azhar Academy of Canada, still under

construction in Rexdale with bare drywall and ductwork exposed above a

rough concrete factory floor, opened in 1997 with eight students, grew to

120 the next year and now has 260. Typically a new school opens with a

kindergarten class and adds a new grade each year. Most schools go only to

Grade 8 so that by high school children join the public system. ``We are laying the groundwork, so when

they leave here, they will be prepared to face the world with

understanding and with a faith that is unshaken,'' says Nisar Sheraly,

principal of As-Sadiq Islamic School, in Thornhill. ``We'd

like them to grow up as proud Muslims who also can say, `We are Canadian.'

''

It's the oldest Islamic school in the Toronto area and one of the few located in a traditional school building. It has a gym and a well-equipped library. When classes begin after the afternoon prayer, a Grade 7 class is analyzing the poem The Cremation of Sam McGee. Boys and girls sit sharply divided in rows on separate sides of the classroom. ``What is your feeling in this poem? There's no right or wrong,'' notes teacher Nayyer Rizvi. Raised hands flutter anxiously as both boys and girls offer to answer questions. The next class is on manners. "Our

manners relate directly to our faith,'' says teacher Yusef Gelle. ``It was

what the blessed Prophet Mohammed taught us.'' (Independent schools are increasing overall in Ontario. In 1974 there were 75; last year there were 725. About two-thirds are religious schools, most of them Christian.) Some Islamic schools hire or accept the volunteer services of retired school principals for help in the Ontario curriculum. In addition, students learn Arabic, beginning in junior kindergarten, and Islamic studies including history, civilization and etiquette. Ask Muslim parents why they are drawn to Islamic schools - which rarely have the buildings, the qualified teachers, computer labs or libraries that parents in the public system have taken for granted - and the answer is often the same. Many parents, especially newcomers to Canada, work two or three jobs to send their children to religious schools which emphasize ethics, discipline and morality ``The most important thing is that they should also learn religion,'' says parent Hafeza Rujabally.Families are prepared to tolerate the growing pains and often the poverty of a school in the early years of its development. ``It's a trade off,'' says Jasmin Zine, who has been studying Islamic schools for her Ph.D. at the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education. She has one child in Islamic school and another in public school. ``They would rather have kids in a positive environment and wait until the school can catch up to the standards of the public system with its resources and qualified teachers.'' Some of the schools are painfully poor in the first years of operation. Tuition ranges from $150 to about $350 a month - not enough to cover operating costs and teachers' salaries. Since the schools receive no public funding, the shortfall is made up through fundraising in the Muslim community. At best, teachers earn 85 per cent of public board salaries, as they do at the As-Sadiq. At the worst, they work as volunteers. ``They do it to serve the community,'' says Shaikh al Saeed Mohamed, principal of Al-Azhar. ``They make a sacrifice.'' Many parents, especially those who are newcomers to Canada, work two or three jobs to send their children to religious schools. ``For many it's a big culture shock coming to Canada, they hear of kids going astray and they really fear for their children,'' says Zine. ``It's a way of creating a safe space for kids.'' Some want their children's Canadian education to echo that of their homelands. ``I want them to learn the Qur'an the same way it was taught to me when I was young,'' says Mustaf Ali, a truck driver, visiting the Al-Azhar school intending to enrol his children. ``I want the discipline that comes with Islam. I hear my children saying words I've never heard before.'' Some parents turn to Islamic schools fearing the public school system and reports of bullying, disrespect to teachers, drug and alcohol use. Some feel uncomfortable with the free mingling of boys and girls. Experiences of racism and Islamophobia can also drive Muslims from the public board, says Zine. They turn to their own community. ``They are choosing an alternative system of education that is God-centred and focuses the child on spirituality and academics,'' says Zine. ``Some might call it a cocoon, but it's a metaphor for safety.'' The As-Sadiq Islamic School is set on 10.4 hectares on Bathurst St., the site of a former nursing home. The Jaffari Islamic Centre, a Shia mosque on Bayview Ave., bought the property to establish a school for $2.5 million in 1994. A poster announcing the school's results of the Education Quality and Accountability Office testing hangs from the school's front door. They are above the provincial average. Lack of regulation troubles some Muslims The school had to pay about $1,500 in total for its Grade 3 and Grade 6 students to take the assessment. ``We do it voluntarily, we want to see how we compare with other schools,'' says board chair Dr. Hyder Fazal.Here, he says, the children are not isolated from wider Canadian society, but insulated. The concept explains the separation of boys and girls in classroom seating, particularly in the middle school years. Posters of Islamic scientists and inventors decorate the halls and classroom walls. ``The concept of history in the public school system is Eurocentric,'' says Imam Syed Mohammed Rizvi, standing in the school's science lab, near a poster of Ibn-al Haitham, described as the father of modern optics. While Europe languished in the Dark Ages, there was a flowering in science, mathematics and literature in the Islamic world, he says. ``Here, they have a perspective of their own history and the contributions of Muslims.'' A lesson on environmental studies includes the notion that nature is to be protected for the next generations, something God has given in trust, he says. The school handbook describes a progressive discipline system: from level one, which includes running in halls and incomplete homework, up to level four, ``sexual flirting'' and physical aggression. But principal Sheraly and others say they have few if any discipline problems. ``Bullying in the school yard, punching in

elementary schools, we don't have that here,'' says Kamal Ali, a former

public school vice-principal and now principal of Iqra Islamic School. ``It

doesn't happen because of the extra component of values.'' ``They are almost offended by the question. 'We know what goes on out there, we're not cut off,' they say. ``Many have been in public schools, they all watch TV. They live in society. They say they like being in an all-girls school, there's a feeling of sisterhood, with an almost feminist undertone. ``They feel freer to speak out in class because there's not the tension of boys evaluating them and the self-consciousness of teenage girls when boys are around.'' Fatima Ashraf joined the Islamic Foundation School in Grade 7 after six years in the public system. ``I felt I didn't belong there, that there was no one like me. When there were school dances I didn't go and other kids would ask me why. They didn't understand and it was hard for me to explain.'' She begged her parents to let her change schools. ``Everyone's like me, I feel much happier.'' She warns against getting the wrong

impression of boys and girls being separated. ``We talk with each other, we

do have assignments together. It's just that we shouldn't be fooling around

with them for unnecessary reasons. We're nice together and we know how to

deal with them when we outside - in a modest way.'' The lack of regulation troubles some in the Muslim community. ``There is no real regulation of what goes in the school in terms of standards,'' says Zine. ``There should be more. Even letting them go out for recess - in some schools (located in industrial buildings or commercial areas) it's unsafe so they have nowhere to go.'' The next step is to develop a board of Islamic education, as exists for Jewish day schools, she says. ``A board could impose standards we as a community feel are important.'' |