|

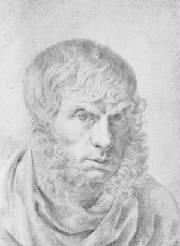

VARIOUS EXPRESSIONS EXPERIENCED BEFORE A SEASCAPE WITH A MONK BY CASPAR DAVID FRIEDRICH, 1810

Heinrich von Kleist, Clemens Bretano, Achim von Arnim

It is magnificent to stand in infinite solitude on the seashore, beneath an overcast sky, and to look on an endless waste

of water. Part of this feeling is the fact that one has made life's way there and yet must go back, that one would like to

cross over but cannot, that one sees nothing to support life and yet senses the voice of life in the sigh of the waves, the

murmur of the air, the passing clouds and the lonely cry of birds. Part of this feeling is a claim made by the heart and a

rejection, if I may call it that, on the part of nature. But this is impossible in front of the picture, and what I should

have found in the picture itself I found only between myself and the picture, namely a claim my heart made on the picture

and the picture's rejection of me; and so I myself became the monk, and and the picture became the dune, but the sea itself,

on which I should have looked out with longing -- the sea was absent.

[There can be nothing sadder or more desolate in the world than this place: the only spark of life in the broad domain

of death, the linely centre in the lonely circle. The picture, with its two or three mysterious subjects (monk, dune, sea),

lies there like an apocalypse, as if it were thinking Edward Young's "Night Thoughts" and since it has, in its uniformity

and boundlessness, no foreground but the frame, it is as if one's eyelids had been cut off. Yet the painter has undoubtedly

broken an entirely new path in the field of his art, and I am convinced that with his spirit, a square mile of the sand of

Mark Brandenburg could be represented with a barberry bush, on which a lone crow might sit preening itself, and that such

a picture would have an effect that rivalled Ossian or Kosegarten. Why, if the artist painted this landscape using its own

chalk and its own water, I believe he would make the foxes and wolves weep: the most powerful praise, without doubt, that

could be given to this kind of landscape painting.

Yey my own impressions of this wonderful painting are too confused, and so, before I venture to express them in full,

I have decided to learn what I can from the remarks of the couples who pass before it from morning till evening.]

I listened to the remarks of the many viewers around me and now relay them as comments on this painting, which is surely

a stage set before which a scene must be acted, for it allows no repose.

(Enter a Lady [the wife of a senior official in the War Department] and a Gentleman [perhaps a great wit]).

LADY (looks in her catalogue): Painting Number Two: a landscape in oils. What do you think of it?

GENTLEMAN: Infinitely deep and sublime!

LADY: You mean the sea, yes, it must be amazingly deep, and the monk is also very sublime.

GENTLEMAN: No, Frau Kriegsrat, I mean the emotion felt by the one and only Friedrich before this painting.

LADY: Is it old enough for him to have seen it too?

GENTLEMAN: Ah, you misunderstand me, I refer to the painter Friedrich, not our great King Frederick. At the sight of this

picture, Ossian strikes up on his harp.

(Exeunt)

(Enter two Young Ladies)

FIRST LADY: Did you hear that, Louise? It's Ossian.

SECOND LADY: No, surely you misunderstand. It's the ocean.

FIRST LADY: But he said he was striking his harp.

SECOND LADY: Well, I don't see any harp. It's really gruesome.

(Exeunt)

(Enter two Connoisseurs)

FIRST CONNOISSEUR: Greysome, yes, it is all terribly gray. how he insists on painting such dry stuff.

SECOND CONNOISSEUR: You mean, how he insists on painting such wet stuff so dryly.

FIRST CONNOISSEUR: I suppose he paints it as well as he can.

(Exeunt)

(Enter a Governess and two Young Ladies)

GOVERNESS: This is the sea near Ru:gen.

FIRST YOUNG LADY: Where Kosegarten lives.

SECOND YOUNG LADY: Where groceries come from.

GOVERNESS: Why did he paint nothing but dull skies? How lovely it would be if he had painteed some men gathering amber

on the seashore.

FIRST YOUNG LADY: Oh yes, I'd like to fish for a nice amber necklace for myself.

(Exeunt)

(Enter a Young Lady with two Children and a few Gentlemen.)

GENTLEMAN: Magnificent, magnificent! This is the only artist who expresses a soul in his landscapes. There is a great

individuality in this picture, high truth, solitude, the overcast, melancholy sky -- he knows what he's painting all right.

SECOND GENTLEMAN: And he also paints what he knows, and feels it, and thinks it, and paints it.

FIRST CHILD: What is that?

FIRST GENTLEMAN: That is the sea, my boy, and a monk who is taking a walk along the shore and feeling sad because he hasn't

got a good little boy like you.

SECOND CHILD: Why isn't he dancing at the front of the picture? Why doesn't he waggle his head like in a shadow-play?

That would be more fun!

FIRST CHILD: I suppose he predicts the weather, like the monk outside our window.

SECOND GENTLEMAN: That's a different kind of monk, my boy, but he does predict the weather, he is the one within the wholeness,

the lonely centre in the lonely circle.

FIRST GENTLEMAN: Yes, he is the soul, the heart, the whole picture's reflection in itself and on itself.

SECOND GENTLEMAN: How divinely the figure is chosen, it is not merely a device to show the height of the other objects,

as in the work of the common run of painters. He is the subject itself, he is the picture; and as he seems to dream himself

into this setting, as if into a sad mirror of his isolation, so the shipless, enclosing sea, which binds him like a vow, and

the bleak, sandy shore, as friendless as his life, seem symbolically to make him spring up again like a lonely dune plant

prophesying its own fate.

FIRST GENTLEMAN: Magnificent, certainly, you are right. (To the Lady) But, my dear, you have not said a word.

LADY: Oh, I felt so at home in front of the picture, it truly touched me. It is truly lifelike, and when you were talking

like that, it was all hazy, just like when I went for a walk beside the sea with our philosophical friends. I only wish that

a fresh sea breeze was blowing and a sail was coming in, and that there was a glint of sunlight and the water was lapping.

As it is, it's like a dream, having a nightmare or feeling homesick -- let's move on, it's making me feel sad.

(Exeunt)

(Enter a Lady and a Gentleman as her guide.)

LADY (stands for a long time before speaking): How grand, how immeasurably grand! It is as if the sea was thinking Edward

Young's "Night Thoughts".

GENTLEMAN: You mean, as if they had occured to the monk here?

LADY: If only you wouldn't make jokes all the time, and spoil the impression. Secretly you feel the same but you want

to mock in others what you yourself reverence. What I said was, it is as if the sea was thinking Young's "Night Thoughts".

GENTLEMAN: Yes, I agree, particularly the Karlsruke second edition, and Mercier's "Bonnet de nuit" as well,

and then Schubart's "View of Nature from its Dark Side" on top of that.

LADY: The best answer I can give you is a similar anecdote. When the immortal Klopstock wrote the line "Dawn smiles"

in a poem for the first time, Madame Gottsched read it and said, "Did she pout as well?"

GENTLEMAN: Surely not as prettily as you when you say that.

LADY: You are beginning to annoy me.

GENTLEMAN: And Gottsched gave his wife a kiss for her bon mot.

LADY: I could give you a "bonnet de nuit" for yours, but a wet blanket would be more appropriate.

GENTLEMAN: Surely I am more like a view of your nature from its dark side.

LADY: You are teasing.

GENTLEMAN: Ah, if only we were both standing there, like the monk!

LADY: I would leave you and go to the monk.

GENTLEMAN: And ask him to make us one.

LADY: No, to throw you in the water.

GENTLEMAN: And then you would be alone with the holy man, and you would seduce him, and spoil the whole picture and his

night thoughts; you see, that's what you women are like, in the end you destroy what you feel, in your very lying you tell

the truth. How I wish I was the monk, forever gazing out alone over the dark, foreboding sea which spreads out before him

like the apocalypse. I would forever yearn for you, dear julia, yet would be without you forever, for longing is the only

magnificent feeling in love.

LADY: no, no, my dear, it is true in this picture too; if you talk like that, I will jump in the water after you and leave

the monk by himself.

(Exeunt)

All this while, a tall, forbearing man was listening with some signs of impatience; I came close to treading on his foot

ahd he answered me as if in so doing I have asked his opinion. "It's a good thing the pictures can't hear, or else they'd

have veiled themselves long ago; people treat them in a very ill-mannered way and are firmly convinced that the pictures are

standing in the pillory here for some secret offence which onlookers must at all costs discover."

"But what is your own opinion of the picture?" I asked. "I am glad", he replied, "that there

is still one landscape painter who pays attention to the strange conjunctures of the seasons and the sky, which produce the

most striking effects in even the poorest regions. True, I would prefer it if he also had the gift and the technique to represent

it truthfully; in this respect he is as far inferior to some of the Dutch School who have painted subjects similar to this

as he is their superior in his overall approach. It would not be difficult to name a dozen pictures where the sea and the

shore and the monk are better painted. From a certain distance the figure looks like a brown smudge; if I had wanted to paint

a monk I sooner have shown him lying down asleep, or set him lower to pray or look about him in all modesty, so as not to

spoil the view for the visitors, on whom the outspread ocean obviously makes a greater impression than the little monk. Anyone

who looked around later for the people of the coast would still find in the monk every reason to say what several of the visitors

have said effusively and confidently, loud enough for all to hear."

These words pleased me so much that I at once went home with the gentleman, where I still reside, and where you will be

able to find me in the future.

[the end]

|