|

my little realm

|

|

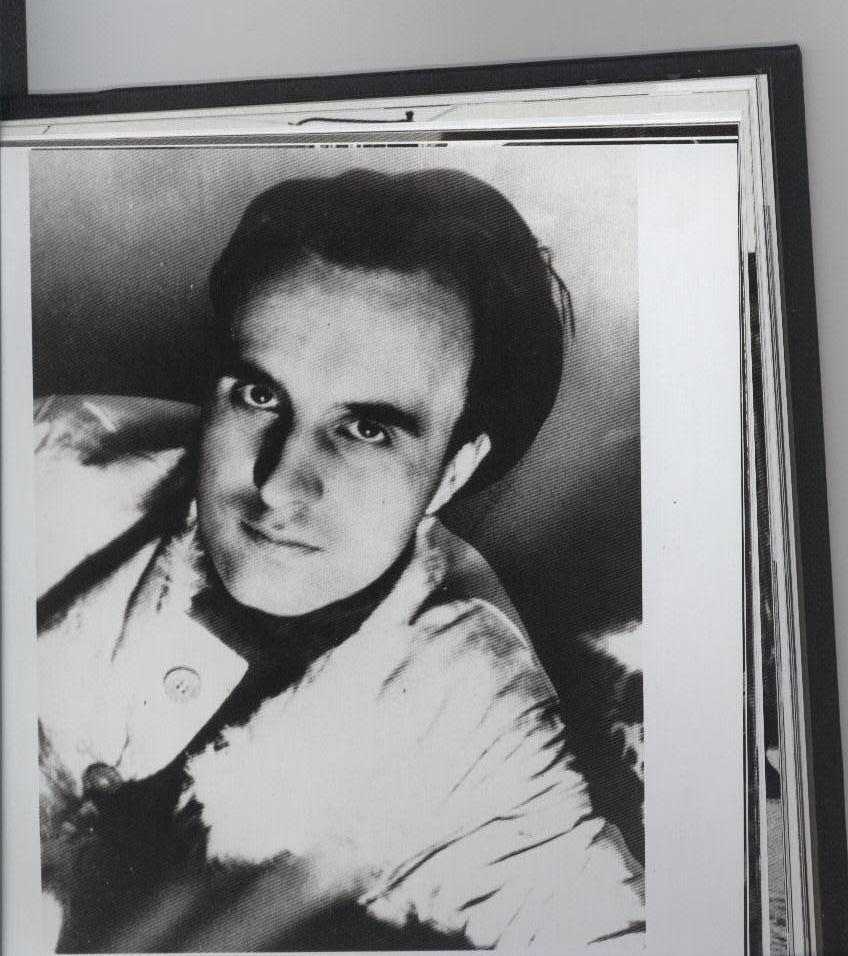

Wolfgang Borchert

|

|

The initiator of the flow of post-war German

literature, Borchert wrote with reality as relentless and unflinching as his haunting stare. He and his work changed

my entire outlook on war and affected me so much that I wrote two of my term papers on him. Wolfgang Borchert (1921-1947) was a veteran of World War

II, and ultimately its victim. At first glance, Borchert's literary heritage is rather small: a few dozen short stories, a

play, and a handful of poems. But in them, the readers of that time saw the reflection of their own thoughts and condition

which no one else dared express so soon, so bluntly; the silent, disillusioned war generation of Germany had found its voice.

His work at once far-reaching and very personal. It is a protest against the war and the system that brought it, a tortured

cry of humanity in the face of the bloodstained, meat-grinding war machine. But above all, it is an intensely personal account

of his own experience of WWII. His foremost goal was to communicate what he went through and raise awareness of that horror.

Borchert was born in 1921, the son of a teacher and a writer.

After finishing his studies in 1939 he became an actor, until he was drafted into the army in 1941. There he served as a panzer

grenadier on the Eastern front, participating in the battles in the Klin-Kalinin area. He saw the purposelessness of the

German-initiated conflict from the very beginning, as one of his early letters testifies: "My comrades, who have arrived here

fourteen days ago, are all dead. For nothing, and again nothing." In early 1942, he was wounded in the left hand and became

ill with diphteria, which brought him home for a hospital stay. Not long has passed before he was wrongfully accused with

voluntary inflecting that wound on himself to get out of military service; he was arrested and held for three months facing

a court martial, until a release for him was arranged. Later that year he was accused again, this time with writing letters

which were "anti-State" and "anti-Party" in their nature. He was sentenced to four months of imprisonment, but with the help

of his lawyer the sentence was reduced to six weeks of "intensified" detainment and the subsequent return to the war front.

During the following months, he developed an illness which henceforth would never entirely leave him and from which he would

die. In 1943 he participated in fierce battles by Smolensk and Kalinin, which would later undoubtedly provide the setting

to many of his stories. By the end of the year his illness intensified, and he would have been discharged from military service

and given a position in one of the fronts theatres, had it not been for another arrest. An evening in close company, with

a political joke or two, landed him an accusation of making defeatist statements and criticizing Goebbles, the Reichs Minister

of Propaganda. Borchert was taken at once to the Berlin-Moabit prison to await his sentence. It was already 1944 and the tide

of war started to turn against Germany. Because of his youth, and the country's need for soldiers, Borcherts sentence was

reduced from execution to nine months of solitary confinement, after which he was sent back to the front into a punishment

battalion, in which he had to fight without a gun. In the early 1945 the company's officers deserted, and the battalion capitulated

to the French troops near Frankfurt/Main. During the transport of the prisoners to the French prison camps, Borchert managed

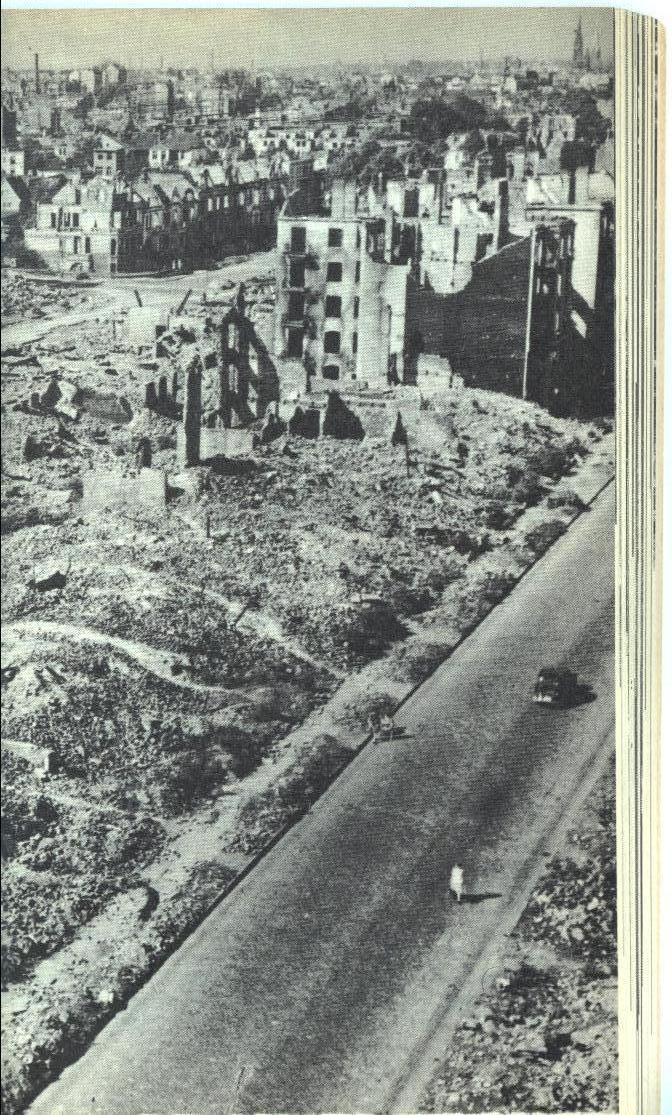

to escape, and set off towards his native Hamburg on foot. After the five-hundred-mile walk, he arrived home on May 10, a

day after the Allied victory, only to find the city in ruins after the countless bombings. His illness once again intensified,

confining him to bed until his death in 1947. He was only 26. It was during these last few years of his life that he wrote,

attempting to come to terms with what he went through and channel the horrors that haunted him onto a page. His work is his

own experience of war, an intensely personal attempt to make sense of it all and to confront the inner demons arising from

it. The photo above was taken several months before his death. Borcherts writing style is reflexive of his traumatizing

experience. There are no elaborate descriptions, or any details at all, for that matter. Everything is reduced to a series

of abrupt, disjointed images, as bare as the snow-covered landscapes of the front where most of them are set. There are no

memorable characters. There are no characters in his short stories, as such; for Borchert, they are just faceless figures

- men, soldiers, widows, stripped of all the tags and labels placed by country and society, but who, despite their anonymity,

do feel, and suffer, and question. This is humanity in its devastating nakedness, in the face of war. The language he uses

is as blunt and immediate as his images, so simple that it almost appears childish and all the more terrifying for the meaning

behind it.

Below are some of his stories in my translation. More will follow soon.

|

|

The Bowling Alley Two men made a hole in the ground. It was quite roomy and almost snug.

Like a grave. It was bearable. They had a gun with them. Someone invented it so one could shoot at people

with it. The people one didn't know at all. One didn't understand their language. And they have never done anything to one.

But one had to shoot at them with a gun. Someone had ordered it. And so that one could shoot a whole lot of them, someone

invented a gun that shot more than sixty rounds per minute. For that, he was rewarded. A little farther away from the two men there was another hole. A head peeked

out of it, which belonged to a man. It had a nose that could smell perfume. Eyes, which could see a city or a flower. It had

a mouth, with which he could eat bread, or say Inge or Mother. The men with the gun saw this head. Shoot, said one. He shot. Then the head was kaputt. It could not smell perfume again, nor see a city

again, nor say Inge. Never again. The two men were in the hole for many months. They made many heads kaputt.

And these always belonged to people they didn't know at all. Who have never done anything to them and whom they didn't understand.

But someone had invented the gun that shot more than sixty rounds per minute. And someone had ordered it. Little by little, the two men had made so many heads kaputt that one could

make a great mountain out of them. And when the two men slept, the heads began to roll. Like in a bowling alley. With soft

thunder. From that, both men awoke. But someone had ordered it, whispered the first. But we have done it, screamed the other. But it was terrible, groaned the first. But sometimes it was also fun, laughed the other. No, screamed the whispering one. Still, whispered the other, sometimes it was fun. Thats what it was. Real

fun. For hours they sat in the night. They did not sleep. Then one said: But God made us so. But God has an excuse, said the other, he does not exist. He does not exist? asked the first. That is his only excuse, answered the other. But we- we exist, whispered the first one. Yes, we exist, whispered the second one. The two men who were ordered to make many heads kaputt did not sleep at

night. For the heads made soft thunder. Then said the first one: And now we live with it. Yes, said the second one, now we live with it. Then the first one cried: Get ready. Its starting again. The two men stood up and took the gun. And always, when they saw a man,

they shot at him. And always it was a man they didn't know. And who never did anything to them. But they shot at him. For

that purpose someone had invented a gun. He was rewarded for it. And someone - someone had ordered it.

The Kitchen Clock They saw him coming towards them from quite a distance, for he stood out.

He had a really old face, but by the way he was walking one could see that he was not more than twenty. He sat himself down

with them on the bench, he and his old face. And then he showed them what he carried in his hand. This was our kitchen clock, said he and looked at everyone in a row, who

were sitting on the bench in the sun. Yes, I have found it again. It was left over. He held out a round, plate-white kitchen clock before him and tapped the

blue painted numbers with a finger. It has no value anymore, he said apologetically, that too I know. And it

is not particularly beautiful. It is only like a plate, with its white enamel. But the blue numbers still look nice, I think.

The hands are only made of tin, of course. And now they do not go. No. It is over with, on the inside, there is no doubt.

But it still looks like it always had. Even though it doesn't go anymore. He made a careful circular motion with his fingertip along the edge of

the plate-clock. And he said quietly: And it was left over. They who sat on the bench in the sun did not look at him. One looked at

his shoes, and the woman looked into her baby stroller. Then someone said: You have lost everything, then? Yes, yes, he said cheerfully, do but think, everything! Only this here,

this was left. And he raised the clock high again, as if the others haven't seen it yet. But it does not go anymore, said the woman. No, no, that it does not. It is done with, that I know well. But otherwise

it is still as it always was: white and blue. And again he showed them his clock. And the best part- he continued, moved-

of that I have not told you at all yet. The best part is, namely, this: Do but think, it stopped going at half past two. Right

at half past two, can you imagine. Then your house must have been bombed at half past two, said the man and

pulled out a lower lip with significance. That I have often heard. When the bombs come down, the clocks stop moving. Because

of the impact. He looked at his clock and shook his head after some consideration. No,

dear sir, no, you are mistaken. This had nothing to do with the bombs. You mustn't always speak of bombs. No. At half past

two there was something entirely different, only you do not know it. That is precisely the joke, that it stopped exactly at

half past two. And not a quarter after four or at seven. At half past two, namely, I always came home. At night, I mean. Always

at half past two sharp. That's precisely the joke. He looked at the others, but they have taken their eyes off of him. He

found them not. Then he nodded to his clock: Then I was hungry, of course, wasn't it so? And I always went straight to the

kitchen. It was always half past two then. And then, then came my mother. I could open the door so very softly, but she aways

heard me. And when I searched for something to eat in the dark kitchen, suddenly the light went on. Then she stood there in

her night robe and with a red shawl. And barefoot. Always barefoot. And our kitchen was tiled. And she made her eyes really

small, because the light was so bright to her. For she had already been sleeping. It was night, you see. So late again, she said then. She never said more. Only: So late again.

And then she warmed up the bread for me and watched as I ate it. And she rubbed her feet against one another, because the

tiles were so cold. She never put on shoes at night. And she sat by me until I was full. And then I could hear the plates

being put away, when I already was turning th light off in my room. Every night it was so. And always at half past two. That

was totally self-evident, thought I, that she prepared food for me in the kitchen at half past two at night. I thought it

totally self-evident. She always did that, you see. And she never said more than: So late again. But that she said every time.

And I thought that it would nevr stop. It was so self-evident to me. All of it. It has always been so. For a while he sat still on the bench. Then he said softly: And now? He

looked at the others. But he found them not. Then he said softly to the clock in its white-blue face: Now, now I know, that

it was paradise. A real paradise. On the bench, everything was still. Then the woman asked: And your family? He smiled at her, embarrassed: Ah, you mean my parents? Yes, they are gone

too. Everything is gone. Everything, can you imagine. All gone. He smiled and looked from one to the other. But they did not look at him. Then he raised the clock high again, and laughed. He laughed: Only this

here. This was left. And the best part is, it stopped going at half past two. Exactly at half past two. Then he said nothing more. But he had a really old face. And the man who

sat beside him stared at his shoes. But he did not see his shoes. He kept thinking of the word Paradise.

Radi Radi came to me this night. He was blond as always and he laughed with

his weak wide face. His eyes, too, were as always: a little anxious and a little insecure. He also had a pair of blond tufts

of beard. Everything as always. But you are dead, Radi, said I. Yes, he answered, please don't laugh. Why should I laugh? You have always laughed at me, I know. Because I dragged my feet so comically

and in the school hall always talked about all these girls that I didn't even know. You have all laughed at me for that. And

because I was always a little anxious, that I know full well. Have you long been dead? I asked. Not long at all, he said. But I fell in the Winter. They couldn't push

me into the ground. Everything was frozen, see. Everything stone-hard. Oh right, you fell in Russia, no? Yes, the very first winter. Don't laugh, but it is not pretty to be dead

in Russia. Everything is so strange to me there. The trees are so foreign. So sad, you know. They're mostly alders. Where

I lie, stand the loud, sad alders. And the stones groan often, too. Because they have to be Russian stones. And the woods

scream at night. Because they have to be Russian woods. And the snow screams. Because it has to be Russian snow. Yes, everything

is foreign. Everything so foreign. Radi sat on my bed and was quiet. Maybe it's only like that to you because you have to be dead there, I said.

He looked at me: You think? It is all so terribly foreign. All of it. He stared at his knees. Everything so foreign. Even

oneself. Oneself? Yes, please don't laugh. That is it. Even oneself is so terribly foreign

to oneself. Please don't laugh, but that is exactly why I came to you this night. I

wanted to talk it over with you. With me? Yes, please don't laugh, just with you. You know me well, don't you? I always thought so. Never mind. You know me full well. How I look, I mean. Not how I am. I

mean, you know the way I look, right? Yes, you are blond. You have a full face. No, say it plainly, I have a weak face. I know it. So- Yes, you have a weak face that always laughs and is wide. Yes, yes. And my eyes? Your eyes were always a little -- a little sad and strange-- You must not lie. I had very anxious and insecure eyes, for I didn't know

whether you would all believe what I was telling about the girls. And then? Was my face always smooth? No, it wasn't. You have always had a pair of blond tufts of beard on the

chin. You thought that no one would notice. But we have always noticed. And laughed. And laughed. Radi sat on my bed and rubbed his palm on his knee. Yes, he whispered.

I was like that. Just so. And then he looked at me suddenly with his anxious eyes. Please, you would do me a favor, yes? But

please don't laugh, please. Come with me. To Russia? Yes, it will be very fast. Only for a moment. Because you know me so well,

please. He gripped my hand. He felt like snow. So cool. So loose. So light. We stood between a pair of alders. Something bright was lying there. Come,

said Radi, there I lie. I saw a human skeleton the way I remembered it from school. A piece of brown-green metal lay by it.

That's my steel helmet, said Radi, it is all rusty and full of moss. And then he pointed to the skeleton. Please don't laugh, he said, but that

is me. Can you understand this? You know me, though, say it, can it be me over there? Do you think? Do you not find it terribly

foreign? Nothing in it reminds me of myself. It is so terribly foreign. One can't recognize me anymore. But I am it. I must

be it. But I cannot understand it. It is so terribly foreign. It has nothing to do with all that I have been before. No, please

don't laugh, but it is all so terribly foreign to me, so unbelievable. He sat down on the dark earth and sadly stared in front of him. With before

it has nothing to do anymore, he said, nothing, nothing at all. Then he picked up some of the dark earth with his fingertips, and smelled

it. Foreign, he whispered, so foreign. He held out the earth to me. It was like snow. Like his hand it was, which had gripped

me earlier: so cool. So loose. So light. Smell, said he. I inhaled deeply. Well? Earth, said I. And? A little sour. A little bitter. Real earth. But foreign, though? So foreign? And so repulsive, no? I inhaled the earth deeply. It smelled cool, loose, and light. A little

sour. A little bitter. It smells good, said I. Like earth. Not repulsive? Not foreign? Radi looked at me with anxious eyes. It smells so repulsive, though. I smelled. No, all earth smells so. You think? Certainly. And you do not find it repulsive? No, it smells damn good, Radi. Smell it once for yourself. He took a little between his fingers and smelled. All earth smells so? asked he. Yes, all. He breathed in deeply. He stuck his nose right into his hand and breathed.

Then he looked at me. You are right, he said. It even smells very good, maybe. But foreign, though, when I think that it is

me, so terribly foreign. Radi sat and smelled and he forgot me and he smelled and smelled and smelled.

And he said the word foreign ever less now. Ever softer he said it. He smelled and smelled and smelled. Then I went on tiptoes back to my house. It was half past five in the morning.

In the garden in front, the earth showed through the snow. And I walked

barefoot on the dark earth in the snow. It was cool. And loose. And light. And it smelled. I stool still and breathed it in.

Yes, it smelled. It smells good, Radi, I whispered. It smells really good. It smells like real earth. You can rest now.

The Cat Frozen in Snow Men walked at night on the street. They hummed. Behind them was a red spot

in the night. It was a hateful red spot. Because the spot was a village. And the village, it burned. The men torched it. Because

they were soldiers. Because it was war. And the snow screamed under their nail-studded boots. Screamed hatefully, the snow.

The people stood before their houses. And these burned. They had pots and children and blankets clutched in their arms. Cats

screamed in the bloody snow. And it was so red from the fire. And it was quiet. For the people stood silently around the crackling,

groaning houses. And that is why the snow couldn't scream. Some had wooden pictured with them. Little ones, in gold and silver

and blue. There was a man to be seen on them with an oval face and a brown beard. The people stared wildly into the eyes of

this very beautiful man. But the houses though, they burned and burned and burned. By this village lay another village. They stood there at the window that

night. And often the snow, the moon-bright snow, was even a little pink from there. And the people looked at each other. The

animals bumped against the stall wall. And the people nodded to each other perhaps, in the dark. Bald men stood by a table. Two hours ago one had drawn a line with a red

pencil. On a map. On this map was a dot. That was the village.And then someone had telephoned. And then the soldiers had made

the the spot in the night: the bloodily burning village. With freezing screaming cats in the pink snow. And the music played

again by the bald men. A girl was singing something. And it thundered sometimes. So very far. Men walked in the evening on a street. They hummed. And they smelled the

cherry trees. It was not war. And the men were not soldiers. But then there was a blood-red spot in the sky. Then the men

did not hum anymore. And one said: Look, the sun. And then they went on. But they hummed no more. For under the blooming cherries

screamed the pink snow. And of this pink snow they will never get rid of. In a half-village the children played with burnt wood. And then, suddenly

there was a white piece of wood. It was a bone. And the children, they knocked the bone against the stall wall. It sounded

as if someone was beating a drum. Tock, said the bone, tock and tock and tock. It sounded as if someone was beating a drum.

And they were happy. It was so pretty and bright. From a cat it was, that bone.

_________________________________________________________________________________  Letter to a friend in early 1941, before entering army and being sent off to the front. Source: Hamburg University's Wolfgang-Borchert-Archiv.

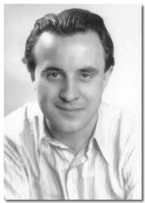

Letter to a friend in early 1941, before entering army and being sent off to the front. Source: Hamburg University's Wolfgang-Borchert-Archiv. In the words of the Archive, "the last civilian photo" of Borchert in spring 1941.  Borchert's handwriting after the war.

Borchert's handwriting after the war.

1946  First collection of short stories, published in early 1947. This is the second posthumous edition from 1949. |