|

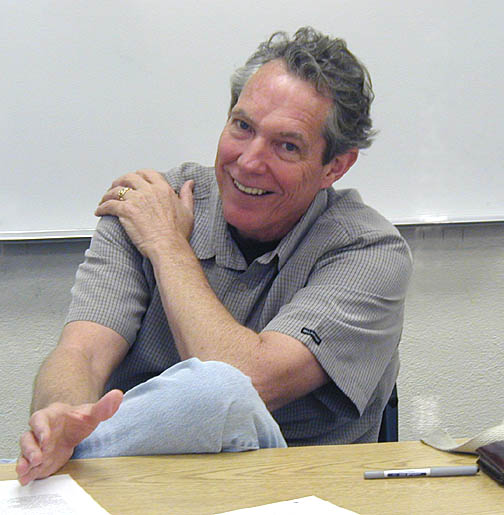

James Blaylock grew up in southern California, and, with the exception of some time spent in coastal northern California,

he has lived in Orange County all his life. He teaches composition and creative writing at Chapman University, and in fact

has been a writing teacher since 1976, about the same time that he sold his first short story, "Red Planet" to Unearth

magazine. He has written fourteen novels as well as dozens of short stories, essays, and articles. His most recent novels

include the following: Night Relics, an atmospheric ghost story set in the Santa Ana Mountains and the city of Orange;

The Paper Grail, a foggy and fantastic romance set along the Mendocino coast in northern California; All the Bells

on Earth, a Faustian mystery that transpires in the old neighborhoods of downtown Orange during a rainy and unusual Christmas

season; and Winter Tides, a ghost-and-murder mystery set in Huntington Beach. His latest novel, The Rainy Season,

was published in August of 1999. Since then he has published two volumes of short stories. Mr. Blaylock is twice winner of

the World Fantasy Award, most recently for his short story "Thirteen Phantasms." His story "Unidentified Objects" was included

in Prize Stories 1990, the O. Henry Awards. James Blaylock grew up in southern California, and, with the exception of some time spent in coastal northern California,

he has lived in Orange County all his life. He teaches composition and creative writing at Chapman University, and in fact

has been a writing teacher since 1976, about the same time that he sold his first short story, "Red Planet" to Unearth

magazine. He has written fourteen novels as well as dozens of short stories, essays, and articles. His most recent novels

include the following: Night Relics, an atmospheric ghost story set in the Santa Ana Mountains and the city of Orange;

The Paper Grail, a foggy and fantastic romance set along the Mendocino coast in northern California; All the Bells

on Earth, a Faustian mystery that transpires in the old neighborhoods of downtown Orange during a rainy and unusual Christmas

season; and Winter Tides, a ghost-and-murder mystery set in Huntington Beach. His latest novel, The Rainy Season,

was published in August of 1999. Since then he has published two volumes of short stories. Mr. Blaylock is twice winner of

the World Fantasy Award, most recently for his short story "Thirteen Phantasms." His story "Unidentified Objects" was included

in Prize Stories 1990, the O. Henry Awards.

Question: What kind of novels do you write? Would you put yourself in a particular genre? How would you describe

your work?

Answer: My novels are published as fantasy or science fiction, although there's no science (except pseudo science)

in any of them. And when there is some variety of pseudo-science – a hollow earth element, say – it's often a

product of the goofy thinking of an eccentric character. I take that back, actually. I wrote several pieces of Victorian science

fiction that involved time travel and fabulous machines, but they were entirely fantastic, with no effort to give anything

scientific credibility – no more, say, than Robert Louis Stevenson's attempt at making the Jekyll and Hyde transformation

credible. There is, however, generally a fantasy element in my work. In my first story, for example, my main character is

traveling on a Greyhound bus to Mars. Or at least he thinks he is. In others, characters peer through keyholes or through

strange old spectacles and see magical realms. Some of my stories have a ghost element, often having to do with the idea that

we carry "ghosts" around with us, that we're haunted by past tragedies, by loss, etc. Also, I've been long fascinated with

stuff, so to speak, with the odds and ends of things that we surround ourselves with and drag around with us and

that become imbued with significance over the course of our lives, that are concrete reminders of what we were at a particular

time, of where we were and who and with whom. A time travel story that I wrote recently had to do with my character's nostalgia

for childhood, and when he revisits his childhood home, which is about to be torn down, he waxes sentimental and digs up an

old coffee can "treasure" that he had buried as a child. When he holds it in his hand, this small personal childhood treasure

launches him into the past, where he comes to the conclusions that he's destined to come to in the story.

It's difficult to see these sorts of things as "science" certainly, and they're also certainly not what we mean by "genre

fantasy." I was told once by a well-meaning editor that I'd appeal to a far larger audience if I did write genre

fantasy, instead of the slipstream sort of thing I write. I'm happy to say that the Library Journal referred to me

as "one of the most distinctive contributors to American magical realism," which is flattering. But I don't think of myself

that way either. In fact, if by "American" they mean North American, then I really don't quite understand the term at all.

Apparently I don't put myself in any particular genre.

Question: What kinds of works do you read, in general? What draws you to those particular works?

Answer: Novels. Essays. I've been on a Patrick O'Brian binge for years. O'Brian, of course, wrote Master and

Commander, which they adapted for the recent film. There are 20 volumes in the series, which means that I can read them

for a good long time – long enough so that I've forgotten enough in the end to make them fresh again. I'm reading them

for the fourth time. I also recently reread Nancy Mitford's novels. I read a lot of G.K. Chesterton, whose essays and articles

for the London Times make up about 15 fat volumes. I incessantly reread bits from my favorite novels, which I keep

on the top of my desk. During the summer I binge on one writer or another. Last summer it was Iris Murdoch, the summer before

that Jane Austen. Next summer I'm going to try to read (reread) a dozen Phil Dick novels. Do I read sf and fantasy? No, not

unless it's one of the rare years when a Tim Powers novel comes out.

Question: What is the best thing about writing, for you? What is the worst? How do you get around that worst thing?

Answer: The best thing about the act of writing are those moments when the writing becomes effortless, when the

various elements of the story – the characters and the setting and the tone – simply begin to do the work for

you. It sometimes happens that I spend hours false-starting and interrupting myself to make sandwiches, and then (for me it's

usually around 3 in the afternoon) I attain some sort of brain-oriented critical mass, and I write a couple of thousand words

in a couple of hours. I find that when the writing is effortless, the best stuff appears, including artistic effects –

structure and metaphor, say – that would seem to be the result of conscious effort, but in fact is more often the result

of unconscious effort.

The worst thing? A non-productive day, when I'm up making sandwiches or running errands or folding clothes when I'm supposed

to be writing. Sometimes the problem is that I'm distracted by other things. Sometimes my brain is simply stodgy. Sometimes

I've got some competing project, and it's easy to walk away from the desk. Periods of low production generally have a sort

of ominous effect on my entire perception of my capacity as a writer.

Question: Recently, the National Endowment for the Arts announced findings that literary reading in America has

declined drastically in the past 20 years. How do you feel about this statement, and what does it mean for American writers

in this day and age?

Answer: It makes me happy that I'm getting on in years. By the time the whole place is illiterate, I'll be drooling

and picking straws out of my hair and it won't matter to me. But seriously...I don't know. If the tendency continues (and

tendencies often fail to continue) then the literary market will get worse than it already is, and it's already gotten fairly

lousy. Speaking of science fiction and fantasy, the market has shrunk drastically in the past 15 years. We saw a lot of interesting

stuff in the "New Wave" era of the 60s and 70s, and in the 80s there was plenty of room for literary fantasy. Now, not only

has the market shrunk, but the vast majority of the titles are crap spinoffs and theme books and the umpteenth Star Wars thriller.

I wonder if Phil Dick, say, would find a publisher today for books like Dr. Bloodmoney or Time Out of Joint

or Now Wait for Last Year. The film industry has evidently caught on to him, but the publishing industry seems to

me to have developed a bottom-line greed that has drastically limited the publication of chancy, literary, eccentric books.

Perhaps we should all learn some other useful work. I've read that crawdads are in demand at the moment. Perhaps I'll start

farming crawdads.

Question: Knowing that you teach creative writing, what is the advice you most frequently give to young writers

about their work?

Answer: I'm anxious that young writers go their own way and not the way of a teacher, say, who has a particular

mind set about what constitutes good writing. Also, I try to compel students to cut themselves some slack. Maybe it's out

celebrity culture, so to speak, that infects the thinking of young writers, but I run into plenty of them who think that they

ought to be selling their work at 20 or 25 years old. Most successful writers persevere. They're willing to be in it for the

long haul. They're satisfied pulling down rejection slips for a few years. Getting bad stories out of your system is part

of the process.

Question: And now for the obligatory random question: Just how much wood could a woodchuck chuck?

Answer: Actually, I know the answer to that: 2 cords, although they can't stack it and aren't interested in doing

so. They merely chuck.

|