|

Presented by

Wm. Max Miller,

M. A.

Click on Anubis to learn about our logo and banners.

About Our Project

Project Updates

See what's new at the T. R. M. P.

Quickly Access Specific Mummies With Our

Mummy Locator

Or

View mummies in the

following Galleries:

XVII'th

Dynasty

Gallery I

XVIII'th

Dynasty

Gallery I

Gallery II

Including the mummy identified as Queen Hatshepsut.

Gallery III

Including the mummy identified as Queen Tiye.

Gallery

IV

Featuring the controversial KV 55

mummy. Now with a revised reconstruction of ancient events in this perplexing

tomb.

Gallery V

Featuring the mummies of Tutankhamen and his children.

Still in preparation.

XIX'th

Dynasty

Gallery I

Now including the

mummy identified as

Ramesses I.

XX'th

Dynasty

Gallery I

XXI'st

Dynasty

Gallery I

Gallery II

21'st Dynasty Coffins from DB320

Examine the coffins

of 21'st Dynasty Theban Rulers.

Unidentified Mummies

Gallery I

Including the mummy identified as Tutankhamen's mother.

About the Dockets

Inhapi's Tomb

Using this website for research papers

Acknowledgements

Links to Egyptology websites

Biographical Data about William Max Miller

Special Exhibits

The Treasures of Yuya and Tuyu

View

the funerary equipment of Queen Tiye's parents.

Tomb

Raiders of KV 46

How thorough were the robbers who plundered the tomb of

Yuya and Tuyu? How many times was the tomb robbed, and what were the thieves

after? This study of post interment activity in KV 46 provides some answers.

Special KV 55 Section

========

Follow the trail of the missing treasures from mysterious KV 55.

KV

55's Lost Objects: Where Are They Today?

The KV 55 Coffin Basin

and Gold Foil Sheets

KV 55

Gold Foil at the Metropolitan

Mystery of the Missing Mummy Bands

KV

35 Revisited

See rare photographic plates of a great

discovery from Daressy's Fouilles de la Vallee des Rois.

Unknown Man E

Was he really

buried alive?

The

Tomb of Maihirpre

Learn about Victor Loret's

important discovery of this nearly intact tomb in the Valley of the Kings.

Special Section:

Tomb Robbers!

Who were the real tomb raiders?

What beliefs motivated their actions? A new perspective on the ancient practice

of tomb robbing.

Special Section:

Spend a Night

with the Royal Mummies

Read Pierre Loti's eerie account of

his nocturnal visit to the Egyptian Museum's Hall of Mummies.

Special Section:

An

Audience With Amenophis II Journey

once more with Pierre Loti as he explores the shadowy chambers of KV 35 in the

early 1900's.

Most of the images on this website have been

scanned from books, all of which are given explicit credit and, wherever

possible, a link to a dealer where they may be purchased. Some images derive

from other websites. These websites are also acknowledged in writing and by

being given a link, either to the page or file where the images appear, or to

the main page of the source website. Images forwarded to me by individuals who

do not supply the original image source are credited to the sender. All written

material deriving from other sources is explicitly credited to its author.

Feel free to use material from the Theban Royal Mummy Project website.

No prior written permission is required. Just please follow the same guidelines

which I employ when using the works of other researchers, and give the Theban

Royal Mummy Project proper credit on your own papers, articles, or

web pages.

--Thank You

This website is constantly developing and contributions

of data from other researchers are welcomed.

Contact The Theban Royal Mummy Project at:

anubis4_2000@yahoo.com

Background Image: Wall scene from the tomb of Ramesses II (KV 7.) From Karl

Richard Lepsius, Denkmäler (Berlin: 1849-1859.)

| |

Special Exhibit

The Tomb of Maihirpre

Gallery I

Opened February 17, 2001

In

March, 1899 (exactly one year after his discovery of the cache tomb of Amenhotep

II) Victor Loret ordered his workmen to make a series of sondages in an

area of the Valley of the Kings between the tombs of Tuthmosis

I (KV

38) and Amenhotep

II (KV

35.) He eventually uncovered a shaft, approximately twenty six feet

deep, with a small chamber cut into one side. Loret descended the shaft, entered

the chamber, and made another remarkable find: the first essentially intact tomb

ever found in the

Valley of the Kings. Inscriptional evidence indicated that the small tomb (KV

36) belonged to a man named Maihirpre.

His funerary equipment constituted the most complete assemblage of such objects

found in the Valley up to that time, and would remain so until Theodore Davis

discovered the tomb of Yuya and Tuyu (KV 46) in 1905.

Obviously of 18'th Dynasty derivation, the exact

date of the burial is still disputed, and evidence from the tomb can lend support to several different dating schemes. A linen

wrapping found on Maihirpre's mummy bears the cartouche of Hatshepsut.

Influenced by the presence of this cartouche, Steindorff speculated that

Maihirpre might have been a companion of Tuthmosis I, Hatshepsut's father.

Quibell also based his conclusions on the Hatshepsut cartouche (as well as

on pottery considerations) but argued that the tomb should be dated to the time

of Tuthmosis III, and

Daressy accepted Quibell's dating in his Fouilles.

Today, some researchers believe that the linen wrapping with the Hatshepsut

cartouche was a kind of antique, old

in Maihirpre's lifetime, because other objects in KV 36 clearly point to periods

later than that of the female Pharaoh. One of these, a beautiful glass vase, has

been dated to the reign of Amenhotep II on stylistic grounds. In his 1908 Guide

to the Cairo Museum, Gaston Maspero also dates Maihirpre's burial

to the reign of Amenhotep II, a view which was shared by Hayes, G. E. Smith, and

Cyril Aldred. However, Maspero changed his mind in the 1915

edition of his Guide, in which he dated KV 36 to the time of

Amenhotep III,

a date which was also accepted by Rex Engelbach.

Maspero probably based his view on a consideration of the box and

loincloths of Maihirpre found along with a fragmentary box of Amenhotep

III in

1902 by Howard Carter. Maihirpre's

coffins, sarcophagus and canopic equipment (see below) bear a close

stylistic resemblance to the funerary ensemble of Yuya and Tuyu,

and would also seem to derive from sometime during the reign of

Amenhotep III. C. N. Reeves dates KV 36 to the time

of Tuthmosis IV, a view also held by Alfred Lucas and his reviser, J.

R.

Harris.

Never properly published by Loret,

the only account of the discovery written while the objects were still in

situ within KV 36 was penned by Georg

Schweinfurth, a botanist, and appeared in the popular German magazine Vossische Zeitung on

May 25, 1899. Three years later, Georges Daressy published photographic plates

of the mummy and the tomb's contents in his Catalogue General des Antiquites Egyptiennes du Musee du

Caire:

Fouilles de la Vallee des Rois ([Cairo, 1902,] pp. 281-298) and this long out of print book has remained

the only extensive photographic record of the find ever published. Unless otherwise

indicated, the photographs of Maihirpre and his funerary equipment used on this

website are from Daressy's work. They provide a

valuable visual record of an important Egyptological discovery that has

been largely forgotten by the general public today.

(See color photo of Maihirpre’s mummy [from Forum égyptologique L'Egypte pharaonique et celle d'aujourd'hui.] To learn more about Maihirpre and his tomb, see Natalia Klimczak’s article [available on the Ancient Origins website for June 15, 2016.])

Go

to KV 36 Bibliography

The

Mummy of Maihirpre The

Mummy of Maihirpre

Maihirpre's mummy (at right and above) was found

resting in a nested set of two coffins contained within a large rectangular

wooden sarcophagus. Schweinfurth reported that thieves had removed some of the

bandages from the mummy, and his statement was confirmed by Daressy, who added

the detail that large sections of bandages had been cut with a sharp instrument

which had been applied with particular force to the bandages of the legs. Reeves

dates this illicit activity in Maihirpre's tomb to the Ramesside period based on

the evidence of 20'th Dynasty ostraca found in the vicinity of KV 36 by Howard

Carter in 1902.

In spite of its ill-treatment by tomb robbers, Maihirpre's

mummy retained its cartonnage mummy mask and still had about a dozen different

articles of jewelry in place among the tattered bandages or lying loose in the

coffin. Among these were bracelets, collars, plaques, and a scarab. The

embalming incision was still covered with a plain gold plate which the thieves

had also managed to miss.

The mummy itself, which was unwrapped on March 22, 1901, was

very well preserved. According to Daressy, Maihirpre was a young man when

he died, probably not much over 20 years of age. Dennis Forbes reminds us that

Daressy was not a trained anatomist and that his estimate of Maihirpre's age at

death is "certainly not expert opinion." However, it seems evident

that Maihirpre was far from being elderly. The fact that his teeth are only

mildly worn is a good indication of a young age at death. The ancient Egyptian

practice of mixing grain with sand and grit in order to aid the grinding process produced

a kind of bread that was dentally abrasive and able to wear down the teeth in

relatively short order.

Maihirpre's mummy measures 5 feet, 4.75 inches and his skin

is dark brown. Daressy believed that this skin color is not the result of

chemical reactions with the embalming materials, and most writers contend the

Maihirpre was at least part Nubian. The curly hair which is so visibly prominent

on the mummy's head would initially seem to confirm Maihirpre's Nubian ancestry,

but is in fact a very realistic wig glued securely in place over his shaven

scalp. Maihirpre's ears were pierced, and he was uncircumcised. No wounds or

obvious signs of illness appear on his body that might help to indicate the

cause of his death, but, as Dennis Forbes points out, Maihirpre has never been

examined by an experienced anatomist. The skin was missing on the soles of his

feet, but this probably occurred during the embalming process.

Maihirpre bore several important titles. He was referred to

as a "child of the k3p," a title normally used to

designate a foreign prince who had been raised from an early age in Egypt.

This practice, which came into vogue during the New Kingdom, helped to cultivate

a sense of loyalty toward Egypt in the children of vassal-state rulers. He also bore the important title "fanbearer to the

king" and was one of the earliest people to hold this designation. Dennis

Forbes points out that this title was often held by the Viceroy of Kush himself. Maspero

speculated that Maihirpre may have been the son of Tuthmosis IV or Amenhotep III

and a Nubian concubine, but no hard inscriptional evidence supports this. It is

hard to imagine a son of the Pharaoh, even by a lesser concubine, who would not

unambiguously proclaim his half-royal parentage in one of his personal

titles.

Mummy Mask Mummy Mask

CG 24096

Maihirpre's mummy mask, made of cartonnage, displays features which date it to

the reign of either Amenhotep II or Tuthmosis IV. It lacks the feather/wing

decorations which characterize mummy masks of the early 18'th Dynasty, but has

not evolved the graceful lines and proportions seen in later masks from the time

of Amenhotep III. It is striped in black resin and gold foil which repeats the

decorative scheme of Maihirpre's outer coffin. The eyes are of inlaid black and

white stone.

Middle

and Inner Coffins Middle

and Inner Coffins

CG 24003-4

Maihirpre's middle coffin (at left in photo) had

its gold foil decoration in place but was never given its coating of black

resin. The absence of the resin indicates that the Egyptians may have applied it

to such coffins only when they were in place in the tomb. This coffin was left

unfinished because it was found to be too small to contain the inner coffin of

the set. It was found, unused and overturned, on the floor in the middle of the

tomb. The inner coffin (at right in photo) is completely gilded. Unlike

the more ornate gilded inner coffins of Yuya and Tuyu, this coffin has hands crossed over the chest

but does not have stone inlays. The decorations

are cut into the gilded plaster.

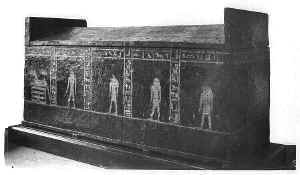

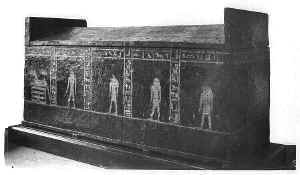

Wooden

Sarcophagus Wooden

Sarcophagus

CG 24001

Maihirpre's large wooden sarcophagus, measuring over 9 feet

in length, is coated with black resin and decorated in gold foil. Anubis and the

Four Sons of Horus line the sides. Isis appears at the foot end. The decorative

scheme mirrors that used on high status coffins of the period.

Wooden

Canopic Chest Wooden

Canopic Chest

CG 24005

Isis, Nepthys, and the Four Sons of Horus,

depicted in gold foil, guard the canopic chest of Maihirpre. The use of gold on

the chest is another indication of Maihirpre's high status. Most non-royal

canopic chests of this period were decorated with yellow paint. The per wer

shaped lid with cornice is similar to that used on Tutankhamen's calcite canopic

chest.

Canopic

Jar

CG 24006

Maihirpre's four calcite canopic jars do not

match. Two have very traditional stoppers with large-faced, human heads, but

the other two have human headed stoppers with smaller, more delicate features. The

jars with the smaller-faced stoppers--one of which is seen at left--possess an

unusual, doll-like quality. Human headed canopic jars were common until the

20'th Dynasty, when animal heads, used to represent three of the Four Sons

of Horus, became the vogue. All four of Maihirpre's canopic jars were inscribed with protective spells and

wrapped with linen.

See

more objects from Maihirpre's tomb:

Book

of the Dead & Osiris Bed

Jars,

Vases & Bowls

Quivers,

Arrows & Dog Collars

|