|

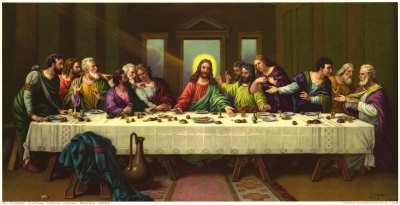

Communion

| The Theology of the Sacraments |

The Greek word used in the early church

for sacrament is mysterion, usually translated mystery. It indicates that through sacraments, God discloses things

that are beyond human capacity to know through reason alone. In Latin the word used is sacramentum, which means a vow

or promise. The sacraments were instituted by Christ and given to the church. Jesus Christ is himself the ultimate manifestation

of a sacrament. In the coming of Jesus of Nazareth, God's nature and purpose were revealed and active through a human body.

The Christian church is also sacramental. It was instituted to continue the work of Christ in redeeming the world. The church

is Christ's body — the visible, material instrument through which Christ continues to be made known and the divine plan

is fulfilled. Holy Baptism and Holy Communion have been chosen and designated by God as special means through which divine

grace comes to us. Holy Baptism is the sacrament that initiates us into the body of Christ "through water and the Spirit"

("The Baptismal Covenant I," United Methodist Hymnal, page 37). In baptism we receive our identity and mission as Christians.

Holy Communion is the sacrament that sustains and nourishes us in our journey of salvation. In a sacrament, God uses tangible,

material things as vehicles or instruments of grace. Wesley defines a sacrament, in accord with his Anglican tradition, as

"an outward sign of inward grace, and a means whereby we receive the same" ("Means of Grace," II.1). Sacraments are sign-acts, which include words, actions, and physical elements. They both express and convey the gracious

love of God. They make God's love both visible and effective. We might even say that sacraments are God's "show and tell,"

communicating with us in a way that we, in all our brokenness and limitations, can receive and experience God's grace.

The Meaning of Holy Communion

In the New Testament, at least six major ideas about

Holy Communion are present: thanksgiving, fellowship, remembrance, sacrifice, action of the Holy Spirit, and eschatology.

A brief look at each of these will help us better comprehend the meaning of the sacrament.

Holy Communion is Eucharist, an act of thanksgiving.

The early Christians "broke bread in their homes and ate together with glad and sincere hearts, praising God and enjoying

the favor of all the people" (Acts 2:46-47a, NIV). As we commune, we express joyful thanks for God's mighty acts throughout

history — for creation, covenant, redemption, sanctification. The Great Thanksgiving ("A Service of Word and Table I,"

UMH, pages 9-10) is a recitation of this salvation history, culminating in the work of Jesus Christ and the ongoing

work of the Holy Spirit. It conveys our gratitude for the goodness of God and God's unconditional love for us.

Holy Communion is the communion of the church

— the gathered community of the faithful, both local and universal. While deeply meaningful to the individuals participating,

the sacrament is much more than a personal event. The first person pronouns throughout the ritual are consistently plural

— we, us, our. First Corinthians 10:17 explains that "because there is one bread, we who are many

are one body, for we all partake of the one bread." "A Service of Word and Table I" uses this text as an explicit statement

of Christian unity in the body of Christ (UMH, page 11). The sharing and bonding experienced at the Table exemplify

the nature of the church and model the world as God would have it be.

Holy Communion is remembrance, commemoration,

and memorial, but this remembrance is much more than simply intellectual recalling. "Do this in remembrance of me" (Luke 22:19;

1 Corinthians 11:24-25) is anamnesis (the biblical Greek word). This dynamic action becomes re-presentation of past

gracious acts of God in the present, so powerfully as to make them truly present now. Christ is risen and is alive here and

now, not just remembered for what was done in the past.

Holy Communion is a type of sacrifice. It is

a re-presentation, not a repetition, of the sacrifice of Christ. Hebrews 9:26 makes clear that "he has appeared once for all

at the end of the age to remove sin by the sacrifice of himself." Christ's atoning life, death, and resurrection make divine

grace available to us. We also present ourselves as sacrifice in union with Christ (Romans 12:1; 1 Peter 2:5) to be used by

God in the work of redemption, reconciliation, and justice. In the Great Thanksgiving, the church prays: "We offer ourselves

in praise and thanksgiving as a holy and living sacrifice, in union with Christ's offering for us . . ." (UMH; page

10).

Holy Communion is a vehicle of God's grace through

the action of the Holy Spirit (Acts 1:8), whose work is described in John 14:26: "But the Advocate, the Holy Spirit, whom

the Father will send in my name, will teach you everything, and remind you of all that I have said to you." The epiclesis

(biblical Greek meaning calling upon) is the part of the Great Thanksgiving that calls the Spirit: "Pour out your Holy Spirit

on us gathered here, and on these gifts of bread and wine." The church asks God to "make them be for us the body and blood

of Christ, that we may be for the world the body of Christ, redeemed by his blood. By your Spirit make us one with Christ,

one with each other, and one in ministry to all the world . . ." (UMH; page 10).

Holy Communion is eschatological, meaning that

it has to do with the end of history, the outcome of God's purpose for the world — "Christ has died; Christ is risen;

Christ will come again" (UMH; page 10). We commune not only with the faithful who are physically present but with the

saints of the past who join us in the sacrament. To participate is to receive a foretaste of the future, a pledge of heaven

"until Christ comes in final victory and we feast at his heavenly banquet" (UMH; page 10). Christ himself looked forward

to this occasion and promised the disciples, "I will never again drink of this fruit of the vine until that day when I drink

it new with you in my Father's kingdom" (Matthew 26:29; Mark 14:25; Luke 22:18). When we eat and drink at the Table, we become

partakers of the divine nature in this life and for life eternal (John 6:47-58; Revelation 3:20). We are anticipating the

heavenly banquet celebrating God's victory over sin, evil, and death (Matthew 22:1-14; Revelation 19:9; 21:1-7). In the midst

of the personal and systemic brokenness in which we live, we yearn for everlasting fellowship with Christ and ultimate fulfillment

of the divine plan. Nourished by sacramental grace, we strive to be formed into the image of Christ and to be made instruments

for transformation in the world. |

|

| Home |

|