| « |

July 2013 |

» |

|

| S |

M |

T |

W |

T |

F |

S |

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

| 7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

11 |

12 |

13 |

| 14 |

15 |

16 |

17 |

18 |

19 |

20 |

| 21 |

22 |

23 |

24 |

25 |

26 |

27 |

| 28 |

29 |

30 |

31 |

Reflections of the Third Eye

25 July 2013

Looper up and down

Now Playing: Michael Angelo on Guinn

Topic: L

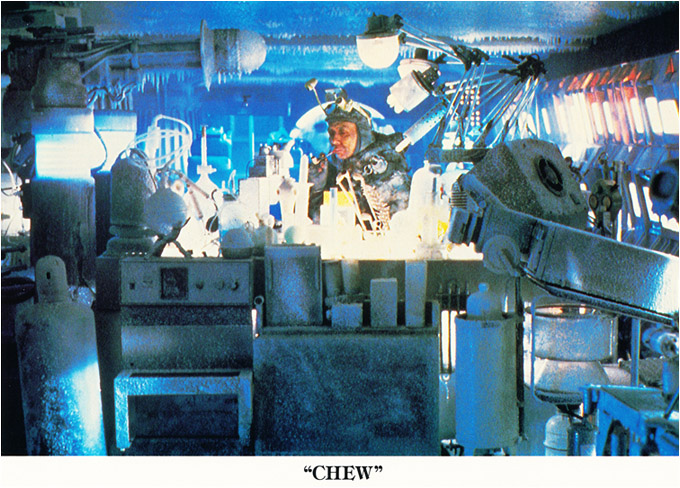

One of the more recent movies to be featured here, LOOPER (2012) had enough pros and cons to foster a livelier response than the 'it's OK, I guess' that's become standard in the current creative doldrums. Like Prometheus, a lot of people think it sucks and will tell you why, most frequently citing the dubious sci-fi set-up for the movie and the fact that it's actually two unrelated stories forced together. And like Prometheus there is a smaller yet clearly devoted fan-base who find the vibe of the movie and its characters so cool that they cannot be bothered to listen to various objections. As the end credits rolled I was in a rare state of cinematic confusion. The alarm inside my head that goes off whenever a movie plot takes a wrong turn, or a character makes an illogical move, or similar defects related to hands-on movie-making, had fired so many times that it barely registered anymore. I didn't have time to keep count, as I watched with fascination how the storyline built an ever-growing pile of parts stolen from other movies. I haven't seen such a multi-derivative film since The Fifth Element, which, incidentally also features Bruce Willis. Two thirds into Looper I had picked up Twelve Monkeys (Willis again!), Terminator, The Boys From Brazil, The Matrix, Carrie, Twilight Zone (the TV series), Signs, Firestarter, Blade Runner, Robocop... you get the idea. The script isn't a copy or exploitation job but a patchwork of concepts and plot twists from a dozen earlier sources. As a patchwork, it is unavoidably messy, and it gets messier by retaining an unnecessary sub-plot about a colleague of the main character and his fate, which presumably is there for pedagogic reasons, so that the less brilliant viewer can surmise the possible fate for the main 'Looper' protagonist. The movie felt overlong at 2 hours, and losing that bit, and perhaps the wasted parts about a clumsy, comic-relief assassin (yep), would have allowed the viewer to focus on the main story. Which, unfortunately, is two different stories with a rather stretched link between them. Neither one is strong enough to carry a movie on its own, not least since so much has been borrowed from elsewhere, and so Looper keeps jumping back and forth much like the time-travelling 'senior' version of the protagonist, who after looking like Joseph Gordon-Levitt with weird make-up all his life, suddenly transforms to look like Bruce Willis around age 45. It's ludicruous enough that I simply didn't understand that it was supposed to be the same person for a few minutes. Meanwhile, the 'other' part of Looper that deals with a child with super-powers and a possibly dystopic future is nicely done, except that again it's all quite familiar, and seems more like an episode of a TV series like the X-Files or Twilight Zone than part of a contemporary big-budget movie. Towards the end, some of the loose ends are tied together as young and old time-traveller battle it out, and there's a nice twist at the very end which makes the movie seem better and more profound than it is. This feeling only lingers until you begin retracking the plot and various scenes in your head, and then all the iffy things suspended in the air come crashing down to the ground, because this movie does not have super-telekinetic powers and can only fake it for so long. In addition to recalling The Fifth Element for the wrong reasons, I was going to say that Looper has the greatest span between its good elements (for one thing, I was never bored) and its bad elements in any movie I've seen in a long time, but that is not true--precisely the same thing applied to Prometheus. Two high-profile movies with recycled ideas, laughable details and overall sloppy execution... I'd say we're looking at the worst creative slump for Hollywood since the late 1980s, eh? 6/10

The director and lead actor collaborated on Brick (2005) which I recently saw and which is clearly a better and more original movie than Looper; well worth seeing.

Posted by Patrick at Lysergia

at 10:38 PM MEST

Updated: 10 August 2013 12:20 AM MEST

19 July 2013

Last Picture Show timewarp

Now Playing: Summer afternoon ambience

A good 12 or 15 years have passed since I last saw Peter Bogdanovich's classic THE LAST PICTURE SHOW (1971), during which time I had forgotten substantial chunks of the plot and cast. So when Randy Quaid pops up on the screen about halfway through I go, "Hey, this must have been a really early part for him", which is true. But then I think "No, wait--he can't be that old--no way was he a teenager in the early '50s!". Do you see? While watching the movie I actually forgot that it was made in the 1970s and assumed it was a contemporary work from the early '50s. Such a timewarp effect is no small achievement for a film. In his retrospective review Roger Ebert addressed this specific issue, noting how the director incorporated cinematic elements from the earlier era in his style, elegantly summing it up as 'the best movie made in 1951'. Except for shooting in black and white, the cues are subtle, and lie not in what is shown on the screen, but how it is shown (one example is the use of illustrative close-ups). It's not at all like the drive for meaningless authenticity that made James Cameron spend zillions on custom-made 1910 cutlery and china that no one's ever going to see in Titanic, but a way to enhance the psychological realism of words and images that are already profoundly touched by realism. The Texas boys in The Last Picture Show wear bluejeans, boots and shirts much like Texas boys in the early '70s, but the look and feel of the movie they're in is that of a bygone era. The cumulative impression grabs the viewer, and Bogdanovich skillfully maintains a steady, unwavering charge to the force field he creates between two poles standing 20 years apart. That is, until the very end, when the sub-plots dissolve and the main characters drop off one by one, and the moving images somehow seem to get older and more distant before your eyes, like a fading photograph. You can literally see 'Sonny Crawford' (Timothy Bottoms) and his small town ageing into history, the empty main street and boarded up shopfronts turning into a nostalgic postcard, Bottoms perhaps lingering as a slightly pathetic heir to local father figure 'Sam The Lion', with fewer customers and duller tall-tales. I can't say for sure if Bogdanovich did something in post-production that creates this effect, or if it's all in my own perception. The other main impression I gather from The Last Picture Show on this viewing is Cloris Leachman's performance as 'Ruth Popper', the depressive woman who is rejuvenated by a love affair with young Sonny. Their story is simple, but also the most powerful of the sub-plots, as we see Leachman go from middle-aged housewife into a radiant, still young woman from Sonny's presence, and then tragically turn into a bitter old spinster as Sonny's interest wanes. Leachman's performance is archetypal, a benchmark for actresses, with inspired support from lighting and wardrobe--observe how her hair changes with the different phases she's in; not just the look of it but also how she carries and handles it. The tour de force is her meltdown when Sonny unashamedly comes crawling back to her. Facial expression, body language, words and voice integrate into a rhythmic organism pushed to the extreme--a human heart at its most naked. You can actually see the emotions rising up from within to wash over her features, different, conflicting, tormenting.* Apparently Bogdanovich felt this was possible, as he asked her not to rehearse the scene in question, but try and nail it on the first take. Which they did. The Academy Award was unavoidable.  All this said, The Last Picture Show isn't what you would call a 'desert island' movie for me. It is very impressive as a cinematic achievement and has aged well, like most 'New Hollywood' films. The themes of the storyline do not grab me as much as the visual look and the specific elements recounted above. This is probably a limitation of the original novel, as I doubt it's possible to do a better cinematization than what Bogdanovich delivered. Taking the story on its own, what exactly does it say? That housewives are bored? That teenagers are horny? That ageing men are nostalgic? That small towns are dull and need to be gotten away from? That the glory days are always in the past? These are not exactly original sentiments, but rather what you see dealt with in the average TV drama. While the movie as a movie still holds up extremely well, I think time has both caught up with and strolled past McMurtry's story as a story. 8/10 All this said, The Last Picture Show isn't what you would call a 'desert island' movie for me. It is very impressive as a cinematic achievement and has aged well, like most 'New Hollywood' films. The themes of the storyline do not grab me as much as the visual look and the specific elements recounted above. This is probably a limitation of the original novel, as I doubt it's possible to do a better cinematization than what Bogdanovich delivered. Taking the story on its own, what exactly does it say? That housewives are bored? That teenagers are horny? That ageing men are nostalgic? That small towns are dull and need to be gotten away from? That the glory days are always in the past? These are not exactly original sentiments, but rather what you see dealt with in the average TV drama. While the movie as a movie still holds up extremely well, I think time has both caught up with and strolled past McMurtry's story as a story. 8/10

NOTE: Bogdanovich reinstated some 15 minutes into the Director's Cut; except for unsuccessfully prolonging the Clu Gulager/Cybill Shepherd pool-table scene, I think all the additions were welcome.

*some of these reflections may be slightly colored by the fact that the movie screening took place on the afterburn of an ayahuasca trip

Posted by Patrick at Lysergia

at 5:58 PM MEST

Updated: 19 July 2013 8:30 PM MEST

17 July 2013

Joel McCrea, Jason Bourne & The Foreign Correspondent

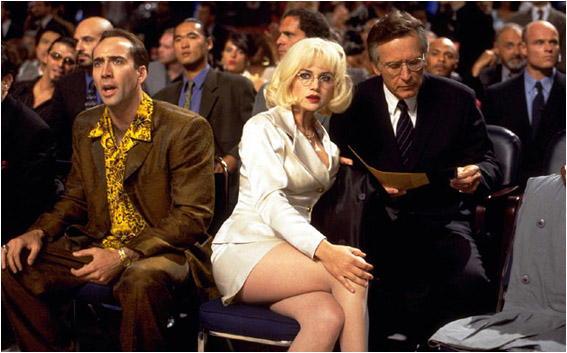

Now Playing: Intolerable Cruelty

As one gets older it seems it gets easier to enjoy movies from eras older than oneself. Perhaps it's simply a case of having seen so much film that one looks past the outer, timebound attributes such as narrative conventions and acting styles, and enjoys the timeless qualities of effective storytelling via moving pictures. Of course, no director made it easier for later audiences to enjoy his works than Alfred Hitchcock, who knew exactly where the keys to movie-making lay, and made sure to use them. Evidence: FOREIGN CORRESPONDENT (1940). This was like a Jason Bourne movie of its time; an intense, complicated rollercoaster ride of a thriller, moving across Europe as the protagonist reveals friends as enemies and even manages a bit of romance on the side. It's also a surprisingly funny movie, perhaps a deliberate wink at the fast-talking screwball comedies of the era from a Hitch who had recently arrived in Hollywood. Twenty years ago I would have been bugged by things like how a car "disappears" when anyone can guess where it went, or how the death of a main character is overshadowed by the comedy of a lost hat. My long-running admiration of Joel McCrea (dating back to seeing Dead End Street on TV in the '70s) may have taken a hit from his performance here, while the back projection car rides would have caused repeated annoyance ("why didn't they just shoot it in a real car?"). Today--I don't really care about those things. I see them, but they don't really register, except as expressions of a contract between movie producer and audience that was different than from what it is now. Hitchcock certainly knew what a contemporary movie should look like, that's what made him Hitchcock. And instead of wasting time being irritated over things that were perfectly alright when they were made, I find myself thinking of the similarities between the Foreign Correspondent and Jason Bourne. This is not a masterpiece from the Hitch, but it's one of his most action-packed and fastest-moving stories, which must have had people pinned to their seats in the grand old movie theatres. Comparisons have been made to North By Northwest, but that is a whole different era, and I would probably look more to The Thirtynine Steps for a sibling in the oeuvre. As for McCrea's performance, he's almost too adept at his part as the anti-intellectual man of action, and Hitchcock undermines his standing as main character by giving a British counterpart almost equal screen time during the second half, taking control of the plot with his ideas and analysis. Apparently Gary Cooper had been offered McCrea's part, which would have been interesting to see, but the most obvious choice to me is Cary Grant, as later Hitchcock movies demonstrate. With McCrea somewhat off the bulls-eye and a fairly mundane cast for the rest, the Foreign Correspondent lacks a bit of the special Golden Era magic, a fact which again directs attention back to the swift direction, engaging script, and a brilliantly executed plane crash that must have been groundbreaking for its time. Special effects barely existed at the time, but the director managed to stage and shoot the long scene of the plane going down, crashing in the ocean, and surviving passengers clamoring on to a broken-off wing, in a way that is nail-biting still in 2013. Probably will be in 2113 as well. For those who want to "get into Hitchcock" there are better choices with an intellectual depth lacking here, but anyone with a moderate interest in old movies is likely to enjoy this proto-Jason Bourne action thriller. 7/10

Posted by Patrick at Lysergia

at 11:08 PM MEST

Updated: 17 July 2013 11:23 PM MEST

27 June 2013

A tribute to John Cazale

Posted by Patrick at Lysergia

at 11:10 PM MEST

24 June 2013

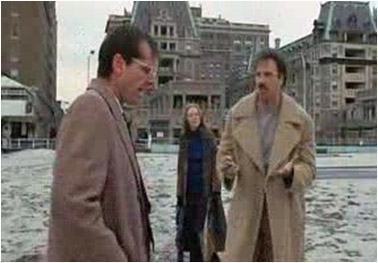

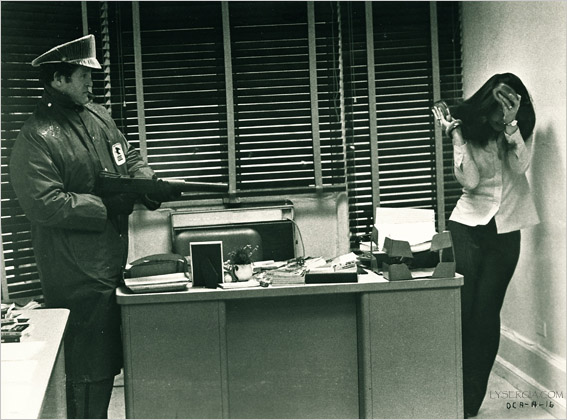

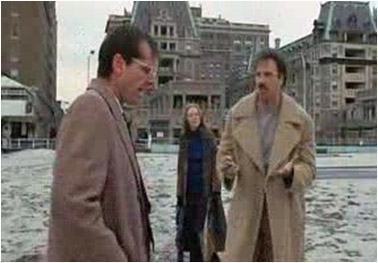

Three Days Of The Condor revisited

Now Playing: High All The Time vol 1

Everyone loves THREE DAYS OF THE CONDOR (1975). It's the kind of movie you could recommend to a co-worker who wants something un-seen that doesn't offend her. With 100% certainty she'll report back that it was 'really good' with a tone of slight surprise in her voice. And she'll be right. Or will she? I loaded up the DVD last night for what I think is my fourth viewing of the 'Condor'. The storyline, which may have the viewer almost as puzzled as Robert Redford's protagonist on the first round, is completely familiar to me, as are a number of crucial scenes. What is not retained in my skull is the special mood of this movie, something we unfortunately can't retain in our cortical memory banks, but need to experience directly for full appreciation, much like the flavor of a favorite ice cream. I remember distinctly that the Condor hit a special mood which I suspect is the reason people like it, but since I cannot summon its presence at will, it is with a certain expectation that I press <Play> and lean back in the chair, lights dimmed and speakers hooked up. The exposition deals with a rather substantial problem, which is to introduce us to a work-place and its employees in a way that makes the viewer respond properly to the shocking mass murder that occurs just a few minutes into the film. We know from the very start that something is going to happen due to classic thriller signals of people secretly staking out the building. Sydney Pollack uses Robert Redford's arrival to introduce us to all, literally, people who are soon to be hit by the murder squad. The mood inside is a pleasant mix of intellectual conservatism and high tech, into which 'Turner' (Redford) injects some friendly, ironic banter. As glimpses are offered of their activities, the mystery of what work actually goes on in this office demands attention. Is it some kind of upscale book store? The faculty building for a nearby private college? Nothing seems quite to fit. This subtly but shrewdly presented riddle requires the viewer to activate yet another brain circuit, in addition to registering the threat from the outside and enjoying the relaxed, bookish atmosphere inside. Rather than giving away the answer, Pollack turns on the ignition of his thriller engine and sets its big wheels in motion by having 'Turner' leave the office to pick up lunch. The half-dozen murders that follow have an appropriately shocking effect in the realm of the peaceful office and likable staff, and Pollack rightly stages the sequence in much the same way as we see Hollywood killings today: striving for realism*, neither excessive nor polite. The spectacular mass murder is also surprisingly void of information for either the victims or the viewer--no demands or requests are made, nothing is asked for, and the killers do not communicate anything except operational dialogue. We do catch a personal glimpse of their leader, whose almost considerate behavior towards one victim plants another enigma for the viewer. As 'Turner' returns to find his colleagues massacred, Redford and Pollack face another artistic challenge, as common sense dictates that Turner should search the entire 2-story office to look for survivors or even perpetrators, finding instead murdered friends over and over, with little variation. Pollack chose to shoot this 'verbatim', turning it into an acting challenge rather than an editing challenge, and while Redford begins the sequence well, he handles the rest mainly by underplaying it, which was probably the wisest move. I'm not sure even a 1970s model Robert De Niro could have pulled those scenes of repetetive horror off in a convincing manner. Unfortunately, Redford does not offer the proper horrified reaction when finding his girlfriend killed, instead treating it with much the same detached disbelief as with his colleagues. If she really was his girlfriend, and it certainly seems that way, why doesn't the main character react more strongly to her death? The issue lingers during the movie as a question-mark, which is not straightened out when Redford later refers to her as a 'friend' with a sad voice. The murdered girlfriend (or not) may be a remnant from the novel the script is based on, and the main character's questionable response to this personal tragedy may not have appeared as a problem until after the editing. Rather than removing her completely (by making her simply another co-worker of Turner), or allowing Redford a scene or two of grief to properly balance the emotional see-saw, Pollack ends up in a problematic space in-between. It's not a major glitch, and Redford's convincing display of terrified confusion following the murders, along with the rich array of questions and the rapid tempo, help take the viewer's mind off it. But at the fourth screening it still bothers me.

Oddly, I found the rapidly blossoming love affair with Faye Dunaway's 'Katherine' fairly convincing. As you remember from Out Of Sight, Jennifer Lopez complains that the 'Condor' couple fall in love too fast, but I don't see it that way. A certain amount of time passes, and it is also clear from the beginning that 'Katherine' is not just an ordinary female kidnapping victim, but an unusual woman with something of a hidden darkness about her. As a role she reminds me a bit of Cybill Sheperd's 'Betsy' in Taxi Driver; another interesting female character who quickly emerges as more than just what the protagonist sees. There is also a 'Stockholm Syndrome' aspect to consider. Pollack does not offer any strong pointers towards this phenomena, which became famous shortly before the movie was made, but the interpretation could be made. In short, I do not agree with JLo, although I may object to the realism of some of 'Katherine's' spy games later in the movie. Three Days Of The Condor is almost certainly the coziest mass-murder movie ever made. Its lingering mood is not one of paranoia, but almost the opposite. We see the killings, Hank Garrett's frightening henchman, Max von Sydow's calculating assassin, the power of the corrupt CIA, and so forth, but it does not register enough to upset the atmosphere that was instilled in the opening scenes. This is a curious, uncommon effect, and almost certainly the reason why so many people like it. The scenes with Redford and Dunaway in 'Katherine's' home are clearly vital to maintain the feeling of warmth and safety: not just for the fleeing 'Turner' but also for the introvert 'Katherine' who, one feels, has never met a man who understands her. She comes into their strange relationship with a different kind of baggage than Turner, yet both of them are looking for the same thing; his quest is of the moment and open to see, her quest is long-term and more abstract, but ultimately it turns out to be the same thing from different perspectives; safety, trust, warmth. The latter aspect is cleverly enforced by the script, which puts the couple wrapped tight in bed after they just met, as Turner needs to sleep and must keep her from calling the police. After some turns of the storyline they end up in bed a second time, now with the more familiar motivation. In another, very well-written scene, Turner describes Katherine's photos of November imagery in what sounds like negative terms, then ends his critique by stating simply that he 'likes them'. Katherine for her part describes how she sometimes takes accidental pictures that does not look like what she intended at all, and those are the ones she likes the most. These exchanges, which are reminiscent of some of Woody Allen's better moments, provide solid nutrition for the idea of their rapidly emerging relationship; it happens through strange circumstances and all via chance, but so do any number of successful real-life affairs.  The cozy feeling, the 'November mood' if you will, is carefully nurtured by Pollack throughout. Von Sydow's assassin is charming, polite, helpful, and just. The CIA director, played with marvellous authority by John Houseman, is educated, wise and thoughtful, while his underling (Cliff Robertson) is charming, straight-forward, concerned. In other words, three classic bad guy archetypes are loaded with positive attributes, and portrayed by actors whose simple presence will lend weight to these assets. The rogue CIA agents that emerge as the real bad guys are not given much in terms of personality at all, and they are cast using fairly unknown actors whose outward appearance confirm the idea of a corrupt government agent. The cozy feeling, the 'November mood' if you will, is carefully nurtured by Pollack throughout. Von Sydow's assassin is charming, polite, helpful, and just. The CIA director, played with marvellous authority by John Houseman, is educated, wise and thoughtful, while his underling (Cliff Robertson) is charming, straight-forward, concerned. In other words, three classic bad guy archetypes are loaded with positive attributes, and portrayed by actors whose simple presence will lend weight to these assets. The rogue CIA agents that emerge as the real bad guys are not given much in terms of personality at all, and they are cast using fairly unknown actors whose outward appearance confirm the idea of a corrupt government agent.

Pollack obviously wanted to create a realistic spy movie in which the natural paranoia was to be resolved and give way towards feelings of trust and safety, rather than the nihilism that we take almost for granted in political thrillers. It would seem a difficult task to turn the table on a genre which very essence is paranoia and cynicism, but Pollack demonstrates how it can be done with familiar, effective tools. The scenography (Turner's office, Katherine's apartment) and weather (rain showers recur and are discussed) and even the wardrobe are geared towards the cozy and familiar, as seen in John Houseman's gentlemanly bow tie and dinner jacket, or the extravagant furlined coat worn by Robertson in one scene. In addition, the fundamental raison d'etre for the whole plot, Turner's frightening theory of a CIA inside the CIA, is given so little attention that it becomes almost a McGuffin, and once this theory is accepted by Houseman's CIA director, the rogue group is effectively terminated. The political message of Three Days Of The Condor is that the CIA is run by decent people who can basically be trusted to do the right thing, and will strike down on corruption or anti-democratic activity. This is not precisely the view we are used to see of the Agency (or NSA), whether in 2013 or 1975, and the benign nature of this message corresponds with the benign, cozy atmosphere of the entire movie. In fact, this encouraging picture of a government agency may have been an impetus for the idea of making a spy thriller where the lasting moods are safety and trust instead paranoia and nihilism, even when several innocent people are killed during the first few minutes. Pollack may also have sensed a need for positive vibes in the wake of Watergate. Either way, some minor quibbles** aside, he pulled it off. 8/10

*by realism I mean what a movie audience has come to consider a 'realistic' gunshot murder scene, not how it actually looks in the real world, which few people thankfully have seen

**one might feel that Redford's protagonist is awfully adept at close-range fighting for a book-worm, as seen in the long and well-directed rumble with the 'Mailman'. However, to Pollack's credit, 'Turner' does lose the fight and is only saved at the last second by 'Katherine'.

Posted by Patrick at Lysergia

at 11:32 PM MEST

Updated: 26 June 2013 12:10 AM MEST

14 June 2013

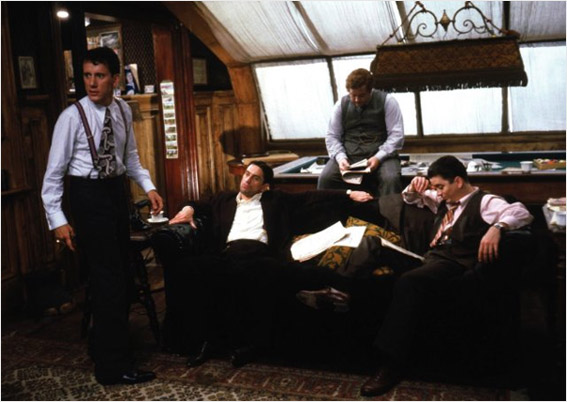

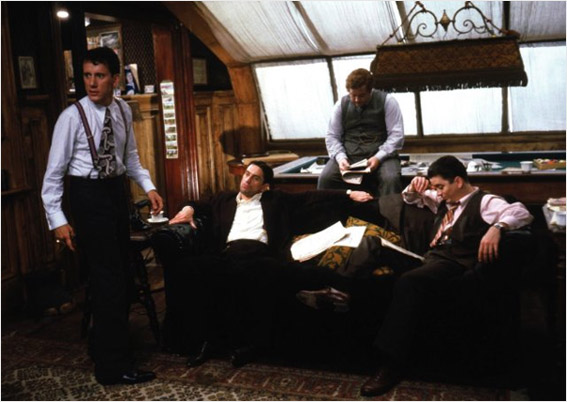

A critical look at Once Upon A Time In America

by Patrick Lundborg

There are many reasons to be grateful for the existence of Sergio Leone's epic ONCE UPON A TIME IN AMERICA (1984). Not only was it a suitably grand finale to a great director's career, but it also found the director leaping boldly into a genre and culture that he hadn't dealt with before. It was a bold enterprise, and it worked. Furthermore, it features one of the last truly committed performances by Robert De Niro who, as we know, could go a long way towards carrying a movie on his own. The script, which went through several overhauls, features an engaging storyline and sharp dialogue, while the scenography recreates a pre-Depression Jewish Lower East Side which looks near organic with its brickwalled mix of factories, tenement buildings and dozens of small corner shops. That the camera work, lighting and color palettes show a master in charge goes almost without saying, but even if it is expected from Leone it nevertheless is a visual delight, not least since the milieu differs so much from his grand Westerns. Revisiting the movie now, I enter with a vague memory of being dissatisfied from the last viewing, a notion which seems curious given the long list of accolades I rattle off above. And for the first hour or so, I have absolutely no idea how I could have had objections to Once Upon A Time In America; I am in fact spellbound by the beautifully balanced narrative and dozens of terrific little details. It's the kind of flawless moviemaking you only get from masters: it is precisely what makes them masters rather than 'good directors'. Leone was obviously inspired by Coppola's Godfather movies, the second one in particular, yet it is the cinematic skill that links the two classics, more than the actual contents. The editing process was infamously troubled as Leone had shot something like 6 hours of film from the script, and breaking it up into two parts was not an option at the time (Bertolucci's 1900 had faded away into box office loss despite an initial enthusiasm over the first part). The studio cut it down to about 2 hours, which reportedly made it near incomprehensible due to three different periods of time and the direct and implicit links between them. Furthermore, Leone left some key moments happening off-screen to be presented via dialogue instead, a choice which maintained the mature, reflective tone of the later eras, but also made scissor incisions problematic. Leone himself came up with a version which ran 3.5 hours, and this 'director's cut' is what most cineasts know, and what is discussed here. The reason the editing and specific problems are brought up here is because I feel that Leone did not quite manage to present an ideally structured epic from his material. The first 90 minutes, circa, are flawless and every bit as good as the movie's reputation has it. As we meet the main characters in their adult appearances (DeNiro and James Woods replacing the excellent child actors), which is the middle of the three ‘arcs’ of time, I register a minor discomfort almost from the start. In musical terms it's not a false note as much as a lost theme. No sooner have we met the grown-up 'Noodles' and 'Max' than we find them engaged in a brutal massacre triggered only by greed. This sequence also introduces the movie's greatest misstep, which is the nymphomaniac blonde played by Tuesday Weld. The acting is fine, but what is the artistic motivation for her encouraging Noodles to rape her during a staged robbery, and for Noodles to go along? This is dark, troubling material, like from a David Lynch film, and there was of course nothing in the opening, adolescent timeframe that prefigured it. Weld returns again for an equally jarring scene which ends with her taking on three of the gangsters at once, an overly long and inexplicably sleazy segment which fills no function in the storyline. It may in fact derive from Bertolucci's aforementioned 1900, which had some very frank sex scenes--but these were integral to the story being told. Finally, this unfortunate thread in Leone's film makes another questionable move by having Max repeatedly display near-psychotic outbursts, none of which had been hinted of before. In order to drive this point home he reacts violently to any insinuation of him being 'crazy', a clichéd scene which is acted out three times without adding anything to the work. Leone has always asked questions about 'good' and 'evil' and how these seemingly absolute terms are in fact strongly dependent on our relative position in the drama. Is a bounty hunter good or evil? Is a man who helps two rivalling gangster clans kill each other good or evil? The seemingly amoral Man With No Name is a brilliantly conceived canvas for the depiction of these complicated questions. Once Upon A Time In America continues with this examination of human nature, and it is perhaps deliberate in its emphasis on evil, by almost any standards, in the second narrative arc. Perhaps the error lies in one of Leone's relatively few vices as a director; a tendency for overstatement, for not knowing when to stop. In his earlier films this came forth as a burlesque element in an Italian stage tradition, where the bandits are so sneering and ugly and the women so voluptuous and erotic that their function becomes primarily symbolic. After introducing us to four realistically portrayed adolescents and having us take part in their adventures in a way that evokes sympathy even as they're a bunch of street punks, there shouldn't be room for a move towards burlesque exaggeration, yet it seems to me that this is precisely what happens as the violence and sex of the second arc plays out. The careful investment in viewer sympathies is ignored and largely lost as the up and coming gangsters are portrayed as rapists, murderers, borderline psychos, but also liars, backstabbers, and misogynists. There is simply very little to like. Leone was presumably showing how the perception of good (or at least likable) and evil is a sliding scale and not a dichotomy, but the lack of subtlety in making his point strips the movie of a most vital asset, the viewer's faith which he had previously earned so brilliantly. The same point could have been made in an elegant, understated way that did not negate the tone of the opening narrative arc, but Leone apparently did not believe in a subtle solution, and so fell back on a cruder and unambiguous form of communication seen in his 60s Westerns. For comparison, consider Scorsese's Goodfellas, which in certain ways is close to Leone's film. In it we see the protagonists commit various heinous crimes, yet as audience we accept them as 'heroes' (or antiheroes) of this particular saga, and we remain concerned about their fate until the end. Exactly how Scorsese achieves this is a different analysis, but largely it is a question of getting several context details just right, and knowing precisely when to push and when to hold back. This is something Leone did not master, and judging by the way he prioritized the second arc in his editing, he was not aware of the problem. After Noodles becomes a rapist (and the rape scene is very painful, very strongly directed, to make things worse) and Max becomes a vicious megalomaniac, it is very hard to care for the characters anymore. And this is a problem, for the movie still has 1.5 hours left to go. James Woods is something of a cult actor, and has created some memorable characters in the edgy, restless, sarcastic style for which he is often type cast. This character has served him well in both drama (Salvador) and comedy (The Tough Way), yet it's hard to point to major roles displaying any wider register than the 'James Woods' archetype. His performance in Once Upon A Time In America is not bad in terms of presence and dialogue, but he fails to contribute anything to the movie. The adult Max does not seem like a convincing development of the adolescent Max, which is perhaps not Woods' fault, but the odd fact that the young Max comes across as emotionally richer and more nuanced indicates that there is a problem with both character and its portrayal. It's a one-note performance where the note is engaging enough not to ruin its context, yet it is not hard to imagine a superior interpretation of the Max role, an upgrade which would also include rewriting it to link back to the first arc and (again) make Max less heartless. As it is, he goes from this devilish, selfserving but also loyal and boyishly likable teenager into an unpleasant psycho gangster with basically no redeeming qualities. When we see Max again during the third arc (set in 1968), his character has gone through yet another metamorphosis, and one gets the feeling that these are more like chess pieces in a moral play than character studies. Woods is allowed a more subtle performance here, but unfortunately the viewer stopped caring about this unsympathetic man and his fate long ago. Woods’ character and performance is not the only problem with the second arc. It seems overlong and eats away screen time that the undernourished and fragmentary third arc could have put to better use. My impression is that Leone, having mastered the opening arc completely, was less sure of which the pivotal scenes and characters were as the script moved beyond the adolescent years. Faced with demands for substantial cuts he was forced into decisions that he wasn't entirely ready for, and unfortunately the surviving emphasis came to land on some of the weaker elements. Although strong in parts, this second arc emerges as the most clichéd and least psychologically interesting segment, showing Noodles and friends simply as successful, ruthless gangsters. As mentioned above, Leone has shown an understanding for the dependence on perspective when it comes to good and evil, but his interest seems to stop there. The crucial process of transition from one to the other, which Coppola displayed so brilliantly with Michael Corleone, is not explored by Leone. In Once Upon A Time In America the viewer is never shown the development (or downfall) of the street punks into mass-murdering gangsters; there is a ‘before’ and an ‘after’, but we are robbed of the how and why. The arrival of the adult Deborah, played by Elizabeth McGovern, is a mixed blessing for Leone’s movie. Something of a reverse positive to Woods' Max, she dominates the second arc alongside Max, and her character is as innocently wide-eyed as Max is unpleasant. As a viewer you wonder what happened with the street-smart and self-assured teenage Deborah from the first part, wonderfully portrayed by Jennifer Connelly. Again, it is not a credible development of the individual, but the parallels to Max extend further than that, as one could argue that Connelly (in her very first role) playing the girl does a better acting job than McGovern, playing the young adult. Rather than Woods' functional but flat performance, McGovern is uneven and seemingly lost, hitting the mark brilliantly in some scenes but being vague and defensive in others. Except for her striking looks, which have an air of Old Hollywood, her most memorable scene is the brutal rape by De Niro's Noodles, which as mentioned above is very effectively directed. The entire sequence leading up to the scene is the most powerful part of the second arc, which would have been much improved if the date-rape had become the organizing center and a lot of unoriginal 'gangster movie' subplots had been removed. Danny Aiello and Treat Williams are introduced with a lot of fanfare, then given almost nothing of value to do; presumably another example of the unsuccessful editing. Through this all De Niro's Noodles is a glue that holds everything together and makes the movie, on the first viewing, seem better and more genuinely epic than it in fact is. The third story arc with middle-aged main characters is more interesting and original, and could have been a powerfully understated conclusion if Leone had awarded it another 10 minutes that were wasted on B-movie sex and violence in the preceding part. De Niro's confrontation with Woods is perhaps more anticlimactic than Leone intended, but various details (such as the terrific middle-age make-up) and good dialogue creates a sense of controlled artistry during the final scenes. But the afterglow of the viewing brings no real sense of closure, instead a number of questions and unresolved problems surface which slipped by at first, due to the strong direction and attractive melancholy of the third arc. An example is the reunion of Noodles and Deborah some 30 years after the date rape, where Leone's natural instinct for loaded scenes and the fine acting of De Niro and McGovern at first instills admiration in the viewer, but this impression is soon overtaken by questions as to the overall credibility of the characters' behavior. It is not made clear why Noodles wants to re-open this old wound, nor why Deborah chooses to see him. On one level it is all terrifically executed; on another level it doesn't quite make sense. Much of the actual plot development of Once Upon A Time In America centers around a mysterious bag with 1 million dollars in a safety deposit box; as clichéd a McGuffin as one can imagine. Had this been a DePalma or Coen brothers movie the viewer might realize and hopefully accept this as deliberate, meta-level playfulness. Unfortunately Leone is quite serious about this bag as a major plot device--it figures at key junctures in the movie, almost like Kubrick's monolith, and appears to be the main motivation for Noodles' actions in the third arc. He even states outright that this million dollar bag has been puzzling him during the decades he was away. It is somewhat disconcerting to find that what started as a brilliant piece of neo-realism about bonding, streetwise teenagers evolves into a simple con man hunt for a bag full of money. If Leone meant something more vital with his McGuffin (such as a symbol for lost trust) he shouldn't have his characters talk and behave as if the physical aspect of it was extremely important. The epic is inexplicably trivialized by a B-movie prop. The director also makes it difficult for himself by inserting this apparently crucial object at sideways angle across the three period arcs. The bag in the box pops up here and there, sometimes full of money, sometimes not. Its trajectory across the complex narrative structure is confusing for the viewer, who is asked to keep track of a fourth story arc, a trivial one at that. It is still possible to stay on the beat with the unfolding multiple timeframes, but it's a frustrating task when there are so many other issues related to the gangster quartet that are only dealt with in passing. As an example, when the movie re-aquaints us with.the middle-aged Noodles after some 30 years, an obvious question is what he's been doing in the interim. Leone acknowledges the question by raising it in dialogue, then dismisses it by offering nothing but vague, flippant answers. As the movie ends, the viewer still hasn't been told what its main character did almost his entire adult life, the same character one learned to know and befriend with utmost care in the opening arc. Noodles is the heart of the movie, then suddenly his actions are of no importance, leaving one to ask what precisely is important, if this is not? Annoyingly, Leone could have made the gap acceptable by 1-2 minutes of poignant dialogue with enough hints about his long absence for the viewer to fill out the rest. There is a similar gap between arc one and two, where Noodles goes to juvenile prison for so many years that he's a grown man when he comes out. What happened inside jail? How did that boy turn into this man? The curious absence of 'sufficient data' is less glaring in this earlier instance, probably because the timeframe is after all shorter, and also since we do know one vital thing of his whereabouts, i e: he was in jail. The 30-year jump from arc two to arc three does not offer even that minimum of information. Instead the viewer, and Noodles too, is made to concentrate on the case of the mysterious million dollar suitcase. This is somewhat ludicrous, and while it is tempting to view these gaps in the storyline as yet another facet of the forced editing, the improper development of the supposedly epic story really falls back on the script. Other gaps, big and small, are strewn about in the second and third arcs. These are not "plot holes" as much as white spots on the canvas of the movie. Things that would seem vital are placed off-screen and briefly recalled in dialogue or, as shown above, not recapped at all. It is hard to discern any logic behind the choice to display scene X while scene Y is replaced by two lines of dialogue. At times you feel that what is not shown -- Noodles in jail and his 30 years in exile, Max' development into a psychopath, the investigation and high-level corruption of the middle-aged Max, the artistic ups and downs for young Deborah, whose dancing was a significant element in the first arc, etc -- would have made a much more interesting movie than the dull gangster shenanigans of the second arc and the mournful reunions of the third arc. In some cases, this less than ideal balance between ‘show’ and ‘tell’ might be explained by the awkward editing process, but overall the script should clearly take most of the blame. Finally, in a way that seems typical for Once Upon A Time In America’s pattern of unfortunate decisions, the two actors that complete Noodles' and Max' hoodlum quartet are not very impressive. There is no need to examine these performances in detail, but one will observe that due to Leone's preference for the gangster activities and lifestyle in the second arc, the two actors get a maximum amount of screen-time in relation to their limited significance to the storyline. Typically, they are entirely missing in the third arc, and no one seems to miss them. A rotund restaurateur who figures prominently in the first half of the movie seems equally expendable. These parts could either have been reduced in the script to liberate several valuable minutes, or used to deepen and explicate the character developments of Noodles, Max and Deborah, rebalancing the movie and make it psychologically credible, without losing the epic sweep of the three arcs. 6/10

Posted by Patrick at Lysergia

at 12:31 AM MEST

Updated: 14 June 2013 1:19 PM MEST

22 May 2013

Black Rain (1989)

Now Playing: The Untouchables

It's easy to forget these days, but there was a long period, perhaps as long as 15 years, where Ridley Scott's standing as an A-list director was shakey at best. He did manage to pull one commercial and critical success out of the hat with Thelma & Louise, but this may have been a case of fortunate timing more than anything else. It certainly wasn't no Alien, anyway. Scott's return to the big league didn't really happen until the 2000s with Gladiator. In the vast doldrums between that movie and Blade Runner almost 20 years earlier floats a string of unmemorable films, some of which are not very good at all. The reason for this crisis of both creativity and productivity will have to be discussed elsewhere, but it's clearly an unusual trajectory that Scott's directing career has followed. Revisiting BLACK RAIN now I am primarily reminded of how disappointed I was with it during its original run, not least since Scott's name still rang with a certain appeal at the time (1989). Conceptually it mixes two popular 1980s Hollywood themes; crooked cops on one hand, and Japan and the Japanese on the other. The story is unexceptional and full of clichés, making one wonder how Scott stomached working on what is B-movie material and nothing else. Some money was allocated for shooting in Japan, which offers a little eye candy, but Scott's occasional winks at magical Blade Runner visuals (light coming sideways or mixed with smoke, rainy inner city streets, foreign neon signs) seem almost offensive given the dreariness of the repetitive, predictable script and jargon-filled and at times silly dialogue. Casting an overaged Michael Douglas as the archetypal loner renegade cop hunted by Internal Affairs was a bad idea which raises a new round of problems beside the writing. Douglas does not convince as a streetwise tough guy, and his voluminous mullet haircut looks pretty awful. The whole presentation is like a clumsy copy job of Mel Gibson's much better developed character in Lethal Weapon. Andy Garcia, who was a rising star at the time, plays his usual sincere and warmhearted Latino, leaving few footprints behind except for a spectacular death scene (the single thing I remembered from my first viewing of this movie). Some of the Japanese actors fare a little better and it's nice to see Kate Capshaw in one of relatively few Hollywood roles post-Spielberg, but none of this changes the fact that Black Rain is a highly unoriginal, surprisingly unintelligent, and at times quite irritating film. One of Ridley Scott's worst. 5/10

Posted by Patrick at Lysergia

at 12:29 AM MEST

Updated: 22 May 2013 12:31 AM MEST

16 May 2013

Child's Play (1972)

Now Playing: Icehockey World Cup

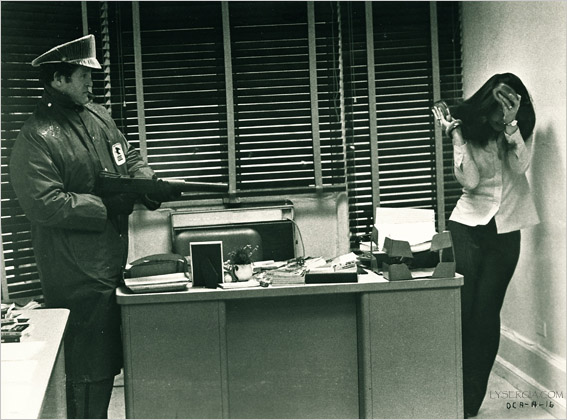

One of the greats among post-WWII Hollywood directors, Sidney Lumet put his name on a very long list of movies with a half-dozen must-see peaks evenly distributed, from 12 Angry Men (1957) through Network (1976) all the way up to Before The Devil Knows You're Dead (2007) released just 2 years before his death. CHILD'S PLAY from 1972 is undoubtedly one of his least known works, and as far as I can tell has never appeared on DVD*. The fact that the makers of the 1990s horror cult series about the evil Chucky doll didn't think twice about using the same title should indicate the earlier film's obscurity. The two works are completely unrelated, even if they share an occult theme and a creepy undertone. Based on a Broadway play, Lumet's movie is set at a Catholic boarding school not unlike the one seen in Dead Poet's Society, and the viewer will observe a few, probably coincindental, similarities between the two. The exposition is both promising and effective and shows the presence of a skilled director. When the viewer is introduced to the new young gym teacher (Beau Bridges) it has already been made clear that something mysterious and unpleasant is going on at the school. Hints of evil forces affecting the young students are recurringly planted, as a parallel plot of a power struggle between two senior teachers (James Mason and Robert Preston) is unfolded in a somewhat over-stated manner. The two parallel stories seem to be linked, but the causal relationships remain hidden and disentangling it provokes a certain viewer involvement. So far, so good. Unfortunately, the transition from play to movie script is far from seamless, creating a movie that works haltingly, in fits and starts, with overlong monologues giving way to moments of brilliance, followed by lots of shots of people running up and down stairs and banging doors. Interesting characters are introduced with fanfare, then given nothing to do. Most problematic is the way Beau Bridges' presumed main character almost disappears about half-way into the movie, only to recur as the final act is set into motion. Some may see this as an improvement as Bridges simply isn't a very good actor, and is given a couple of difficult, rhetoric scenes that he cannot handle well. As Bridges fades out, James Mason takes the center stage with a performance that is on a whole other level than Child's Play in general. In a fully committed effort Mason portrays a stern, traditional Latin teacher who insists on his classic values, both in teaching and in life in general, but is step by step driven towards a breakdown by the harassing 'forces' at the school; forces whose origin he seems to be alone to identify. Unfortunately his part is written too far into melodrama and overstays its welcome towards the end, but this is no fault of Mason's. The lesser known Robert Preston does a good job as a presumed straight-man to Mason's conservative eccentric.

The movie progresses along its uneven trajectory, but does not quite succeed in connecting the mysterious evil that drives the pupils to outbursts of violence with the power struggle between the two teachers. Lumet seems more interested in the letter, and it's possible that Mason's outstanding performance caused a re-balancing of the narrative during the editing. Bridges protagonist is given so little of value to do that he becomes almost superfluous, and there is also a violation of the 'show-not-tell' principle as various side characters discuss the strange goings on. The children are reduced to spooky props, brought out every 20 minutes to enforce the theme of evil in different, sacrilegous ways. One might suggest that the movie had been much more effective if Bridges' character had been replaced with a new student in the class which stands at the center of the goings-on. The final revelation is hardly a surprise to the viewer as the number of alternative scenarios were few, but thanks mainly to Robert Preston's consistent interpretation of his part, there is still a certain pay-off when the truth is laid bare. The final scenes show that Lumet understands what certain horror directors know to be true: groups of children without adults can be scary. But Child's Play could have made much better use of this asset, instead of sacrificing its initial tone of occult mystery for what is basically a power struggle between two academics. If it had been made the year after The Exorcist instead of the year before, it would probably have been re-written into a more interesting and truly supernatural story. This was clearly not an important project for Sidney Lumet, who directs it by the numbers for the most part, and actually manages to botch a couple of dramatic scenes that could have been high-points. As often in his movies he seems most at ease in a clearly defined, recurring space, in this case the faculty quarters, where the camera moves elegantly among the tea trays and essays while the overly talky script is acted out. Neither an occult movie nor a particularly rewarding addition to the long line of boarding school dramas, Child's Play is of interest mainly for James Mason's terrific, soul-baring performance, which deserved a more ambitious and better constructed environment. 6/10

*Apparently it's been released on DVD recently.

Posted by Patrick at Lysergia

at 8:49 PM MEST

Updated: 19 May 2013 1:24 AM MEST

15 May 2013

Coming Home (1978)

Topic: C

I checked another item on my Hal Ashby score card by viewing COMING HOME (1978). Arriving timely with its post-Vietnam concerns and realistic tone, this used to be one of his most widely respected works, though I'm not sure what its standing is today. In any event it is appropriate that I didn't get to see this until now, as it's not a movie for a popcorn teenage mindset. My expectations were pretty high, and basically I thought it was a very good and engaging movie. It wasn't entirely successful however, and my main reservation is with Bruce Dern's part, which seemed poorly outlined compared to the two main characters (Jon Voight and Jane Fonda). Dern delivers his usual overly expressive, silent movie-like acting, which works in some films (like Black Sunday) but hardly so in the delicately balanced world of Hal Ashby.

A sensitive director like Ashby ought to have felt that Dern was the wrong actor to solve the problem with the poorly outlined character, and it's also a curious casting choice in terms of screen presence. The production team would have been wise to pick someone that looks like a marine officer, like Powers Boothe, or Scott Glenn, or Stacy Keach ,or someone like that. Bruce Dern looks like a liberal arts college teacher and lacks the efficient rationality that officers, especially ones with combat experience, would be assumed to display. This might all work better on a re-watch, but it felt to me like a certain magic seeped out the back door due to the Dern factor.

Jon Voight on the other hand is pretty awesome, a reminder of how good he was when his star was still rising. Much of his more recent work tends to have a certain laziness or lack of commitment to it. And it was a nice, possibly deliberate irony to cast 'Hanoi Jane' Fonda in a movie like this. The triangle Voight-Fonda-Dern is the engine of Coming Home, and as you would expect from Ashby, the scenes are painful and powerful with understated precision. The one scene that didn't convince me was where a supposedly psychotic Dern threatens his estranged wife Fonda while addressing her like a Vietnamese enemy. This looked very awkward and broke the spell, and I doubt any actor could have pulled that off. The movie ends on an effective note with a semi-improvised monologue by Voight about the horrors of war that must have looked dubious on paper, but works thanks to Voight's precise performane and the thematic backdrop that Ashby has created. There's also a terrific music score that includes two Buffalo Springfield songs. 7/10

Posted by Patrick at Lysergia

at 12:20 AM MEST

Updated: 10 August 2013 12:46 AM MEST

King Of Marvin Gardens (1972)

Now Playing: High Tide "Sea Shanties"

Topic: K

One of the more extreme cases of the New Hollywood's downbeat 1970s realism, KING OF MARVIN GARDENS was the movie Bob Rafelson made after scoring big with Five Easy Pieces. Rafelson's running mate Jack Nicholson handles the main part in the movie, which is mostly set in the superbly desolate atmosphere of old, pre-Trump Atlantic City in the Winter. However, the movie (named after the Monopoly board game) fell far behind its predecessor in terms of success, and today a lot of people don't even know that it exists. In view of the similarities, an interesting question is why Marvin Gardens didn't communicate with the audience, while Five Easy Pieces did. The plot details have been changed so that we're on the East Coast instead of West Coast, the central relationship is brother and brother rather than father and son, and the protagonist is an introvert writer instead of an extrovert musician, but the fundamental Rafelson tone and pacing are easily recognizable. Both movies are very much character studies with an eye for unusual settings, and in terms of plot one might argue that Marvin Gardens is actually superior, or at least clearer defined, than its predecessor. Nicholson helps his brother (Bruce Dern) with some legal trouble and in the process is brought on board for a holiday resort project on Hawaii, apparently with some local mafia involvement. The brothers and two girlfriends linger in Atlantic City while trying to lay their hands on a bundle of money that would help finance the Hawaii dream, and all the while their vastly different personalities are played off against one another. It's a fairly solid foundation for the type of quirky psychological drama that Rafelson had helped bring into vogue, and his direction skilfully offsets the storyline with incisive looks at the four main characters, both tracks leading forward in unpredictable starts and stops. Outside, the near-empty streets, boardwalks and hotels of old Atlantic City remain present to mirror the sense of homelessness, or lack of belonging in a deeper sense, that the protagonists project. The many exterior shots may stay in the viewer's memory longer than anything else in the movie, and represent a great documentary value in addition to the powerful atmosphere.  Most likely, what kept Marvin Gardens from becoming a classic resides in the handling of the two main characters. People loved, and still love, to watch Nicholson as the sarcastic yet obviously suffering Bobby Dupea in Five Easy Pieces; the combination of strength and resignation was new at the time, and it obviously hit a spot with the post-psychedelic generation. Of course, it was also an extraordinary acting achievement by Nicholson, still today one of the highlights of his career, even if he was just three years out of biker movies and AIP hippie-ploitation flicks. Now, Nicholson does a very good job in Marvin Gardens too, and he accepts the challenge of bringing his first-ever introvert, low-key character to the screen. He would continue to insert this 'other', cast-against-type face of Jack into his acting repertoire now and then, as seen in The Border and About Schmidt, for example. Most likely, what kept Marvin Gardens from becoming a classic resides in the handling of the two main characters. People loved, and still love, to watch Nicholson as the sarcastic yet obviously suffering Bobby Dupea in Five Easy Pieces; the combination of strength and resignation was new at the time, and it obviously hit a spot with the post-psychedelic generation. Of course, it was also an extraordinary acting achievement by Nicholson, still today one of the highlights of his career, even if he was just three years out of biker movies and AIP hippie-ploitation flicks. Now, Nicholson does a very good job in Marvin Gardens too, and he accepts the challenge of bringing his first-ever introvert, low-key character to the screen. He would continue to insert this 'other', cast-against-type face of Jack into his acting repertoire now and then, as seen in The Border and About Schmidt, for example.

The problem with Nicholson's role is that it doesn't offer much space to communicate with the viewer, whether to evoke sympathy or as a psychological riddle. He simply is there, impenetrable and closed for others; on one hand very believable, on the other hand not enough engaging. This is a given risk when putting an introvert, stone-faced character at the center of the work, and the opening up of some type of channel for closer familiarization can easily look like a cheap psychological shot. Rafelson and Nicholson put their trust in the credibility of the character to connect with a mature audience, but in my view it isn't quite enough. Opposite Nicholson's silent enigma we have Bruce Dern's extrovert, eternally optimistic screw-up, a part that could very well have been handled by Nicholson (this reversal of casting may indeed have been deliberate). Unlike Coming Home a few years later (see review) Dern's jittery presence is appopriate to the part, and I believe this is one of his better performances. The casting of him as a presumed biological brother to the not very lookalike Nicholson is a bit awkward. The most important problem, however, is the same once more: his character does not evoke a useful response with the viewer. There are both lovable and despicable scoundrels, and neither script nor Dern go enough of a distance to make this a person whose fate one wants to care about. Given his failed business plans and interaction with mobsters the deck is stacked against Dern's protagonist from the start, and there isn't enough benevolence to compensate for it. So ultimately, the King Of Marvin Gardens sets two very different and not overly likable brothers against each other, with the expected bursts of animosity, nostalgia and blood-tie responsibilities. We learn a little more about them from their interplay, but it's nothing that changes the fundamental impression given from early on. Nicholson remains a loner, Dern remains an irresponsible screw-up, and their ways will part again after this brief reunion. The female companions get plenty of screen-time to work as dialogue sparring partners for the two brothers. Ellen Burstyn, much in demand at the time, is solid as usual as a former beauty queen in a love/hate relationship with Dern's unreliable hustler. The couple have sort of adopted a young woman with a striking, slightly eerie presence which seems perfect for the movie and its setting. Apparently an amateur actress named Julia Anne Robinson, this casting gamble pays off, and the sub-plot showing the competition between the ageing, former beauty pageant girl and the younger, future one offers a variant on a mother/daughter conflict that is both inspired and touching; clearly one of the film's assets. Burstyn is also involved in a plot twist towards the end that should surprise any first-time viewer, and may seem to jar with the dominating tone of status quo. After this long litany about why and how King Of Marvin Gardens doesn't live up to Five Easy Pieces, I still have to say that I like this movie very much, and I believe those with a faiblesse for the radical '70s style of cinema will agree. There isn't enough rebellion and extroversion here to make a classic, but there is nevertheless a brilliant setting and an intriguing, original quartet of people. Bob Rafelson was one of the more adventurous directors of New Hollywood, and this neglected work offers up a rich catalog of aesthetic issues and cinematic questions that the post-Easy Riders era raised. To modern viewers with no particular interest or experience with this style the movie might look weird and possibly disjointed, but I do believe the Atlantic City milieu and Nicholson's understated performance will continue to fascinate. 7/10

Posted by Patrick at Lysergia

at 12:17 AM MEST

Updated: 10 August 2013 12:45 AM MEST

14 May 2013

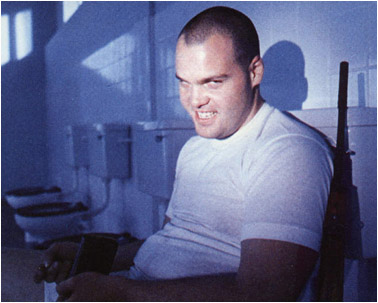

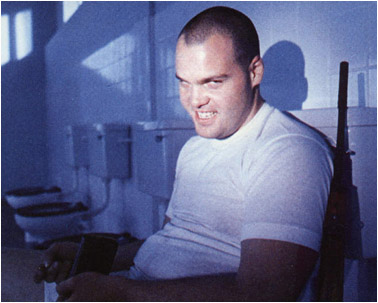

Full Metal Jacket's Gomer Pyle reconsidered

Now Playing: Paul Page "The Reef Is Calling"

Topic: F

This is it. After years of self-deception, I'm finally throwing in the towel. It just doesn't work, or doesn't make sense, no matter how much I would like it to. What am I talking about? Well, in short, this:

I have gone on record many times calling Full Metal Jacket one of my favorite movies from one of my favorite directors. Unlike most of Kubrick's works it is very realistic in tone and look, which is one reason I've rated it so highly. I was there when the Usenet Kubrick forum carved out the standard 101 analysis of the movie, chipping in with a thought or two but generally remaining on the sidelines while the expertise flowed back and forth. This high-brow group had earlier improved my understanding of The Shining in several useful ways. For example: It is not true that Jack Nicholson makes a poor portrayal of a drunk in the bar scene with 'Lloyd', because he is not actually drunk; he is a man going insane who imitates a drunk, as part of the ghostly drama evolving inside and around him. In other words, Jack plays a nutcase pretending to be drunk. I admired the ingeniousness of this viewpoint, but after a while I realized that it was probably true. I had erred in not fully understanding the context of the scene, mistaken multilayered personas for weak acting. Following this crash course in Kubrickiana, I became rather cautious in voicing any detailed opinions on his movies except on a general note of (usually) appreciation. The fact that these works seemed to get better with each repeat viewing confirmed the soundness of this approach. Applying this on Full Metal Jacket, I concluded that it was one of Kubrick's very best; flawlessly executed as always, but also gaining an edge from its strong anchoring in actual events, i e: US marines in Vietnam. Now, every once in a while during the half-dozen times I've watched it, a little voice of dissent would clear its throat and question whether Vincent d'Onofrios characterization of Leonard aka 'Gomer Pyle' really needed to be so radically broad, given the realistic tone and look of the rest of the movie. But the lesson I had learned from debating Nicholson's performance in The Shining would bear down on this polite little dissident, and insist that d'Onofrio's performance was right on the money, it was simply a case of me failing to understand how the larger bolts of the narrative machine came together. Besides, with time the whole thing would surely look appropriate and maybe even prophetic. This was, after all, Kubrick. So I went with this self-editing and professed my love for Full Metal Jacket and how its three parts were brilliantly juxtaposed etc etc & blah-blah. The case of Gomer Pyle was simply above suspicion, but there was always a nagging feeling that I wasn't done with the movie. So when recently Full Metal Jacket came on TV, I figured I'd take another round with it as I had nothing better to do. This improvised screening meant eschewing the ritual of selecting the DVD from the shelf and placing it in the player, which may have contributed to the more critical mindset I brought to this viewing. Or maybe the time had simply come for a new perspective. Rather than sort of blanking out the scenes where it looked like d'Onofrio's performance was way off the wall, I watched them closely to try and figure out the motivation behind them. Because it's not Vincent d'Onofrio (a very good actor in my opinion) we are watching, but rather Stanley Kubrick's instructions to Vincent d'Onofrio. Any Kubrickian knows that the Master wouldn't commit a single shrug or nosepick to celluloid without thinking it through, and so whatever d'Onofrio had his character do, it was what the omniscient director wanted. And given my general respect/awe for Kubrick, I figured there was some justification or logic in there that I simply didn't understand, just like in The Shining. Right. Except that this time, the rationalization didn't work. I saw nothing but an actor doing a decent job 90% of the time, then skid off the road during the remaining 10%. After being portrayed as a slightly dimwitted and undisciplined grunt among others not much superior, Leonard unexpectedly goes 'full retard' in a scene where Matthew Modine's 'Joker' shows him how to tie his shoelaces. Not only is the basic scene questionable, but the exaggerated look of childlike adoration on Leonard's face jars badly with the apathetic loser we've seen so far, and with the brutal world of adult men that is the world of Full Metal Jacket's first act. It's an embarrassing, cringeworthy scene, not so much because of the acting but because it doesn't make sense in the context of the movie. What does the movie gain from this? If anything, our sympathy for the underdog is diminished rather than heightened, and, most of all, the harsh naturalism that is one of the strongest assets is suddenly undermined. Towards the end of the Parris Island sequence, we are told that Leonard aka Gomer Pyle 'can't hack it anymore'. It is an unnecessary piece of dialogue because d'Onofrio portrays Leonard's breakdown by going over the top in a way that leaves little room for misinterpretation. Instead of being Joker's starry-eyed protagonist he has turned into a psychotic war machine living in symbiosis with his rifle. As the freshly baked marines gather to receive their combat assignments, Leonard gives off a blank psycho gaze while his fellow soldiers cheer and laugh. What he shows is in fact the Kubrick Stare, familiar from earlier movies such as 2001, A Clockwork Orange and The Shining. In the Kubrick Stare, the protagonist is looking straight into the camera from beneath a prominent forehead and eyebrows, giving off an arresting look of predatory concentration. If this was the peak of d'Onofrio's 'psychotic' interpretation of Leonard it would have been a fitting signal as well as a thought-provoking reference to Kubrick's earlier fims. But of course, this is not the case, because the grand finale of Act 1 takes place in the Head (so branded with a sign on the door) and finds a Leonard more psychotic than anything psychotic you've ever seen before, except maybe in bad Psychotronic features. The Kubrick Stare has been augmented with a crazy smile to create a truly unsettling appearance which, unfortunately, looks quite incredulous and, once more, clashes badly with the realistic tone of the preceding scenes and indeed the entire work. Not only does he look like something from a comic book, but his voice has become completely altered as well, from mild-mannered sad-sack to a devilish sneer. The inevitable logic of the actual events that transpire in the Head needn't be dwelled upon, and the interesting question here is again: what does this scene, and the whole Parris Island segment, gain from the highly theatrical performance delivered by d'Onofrio during the climactic scenes? As pointed out above, there is nothing random or unplanned in a Kubrick movie: d'Onofrio portrays Leonard this way because Kubrick has encouraged him to do so. But why did the director want this? 25 years have passed since Full Metal Jacket premiered. The idea that time would reveal the meaning of elements that seemed dubious on early viewings may apply to some aspects of the work, but as far as I can tell, d'Onofrio's overacting still looks like overacting in 2013, and these scenes stick out like a handful of clumsy, inexplicable brush strokes on an otherwise beautifully realized painting.

This most recent viewing of Full Metal Jacket also helped clarify a couple of aspects to the middle act that have troubled me somewhat. Again, I was helped by the excellent critical 'walk-throughs' compiled by the Kubrick fans on the internet.

Posted by Patrick at Lysergia

at 8:46 PM MEST

Updated: 10 August 2013 12:45 AM MEST

30 April 2013

What are you doing, Dave?

Now Playing: Real Madrid-Dortmund

Topic: *Memorabilia & such

After three disappointing movies in a row, here's an original promo photo from a movie which rarely appears in the same sentence as 'disappointing'.

Posted by Patrick at Lysergia

at 10:19 PM MEST

29 April 2013

Carnal Knowledge (1971)

Now Playing: Can "Monster Movie"

Topic: C

German-born director Mike Nichols saw an early break-through with The Graduate in 1967, a movie which may appear almost incomprehensible to teenagers today but was a huge critical and commercial success at its time. Only Nichols' second feature movie, it dealt with the woes of coming of age in an upper middle-class '60s far from the sociocultural street theatre of Merry Pranksters and Mario Savios alike. Four years later Nichols took on a work that was wholly adult in both subject and tone; you may have to be 25 just to understand the title. Carnal Knowledge is a character study that follows two young college friends through their friendship, relationships, and the occasional intertwining of the two. It's talky, seemingly ad libbed at times, moderately psychological, depressing but sometimes fun, and would, in 10 years time, have been directed by Woody Allen rather than Mike Nichols. Allen had undoubtedly made much better use of the New York City setting than Nichols, who wastes his opportunities by using generic back projection shots instead of filming on location. This drawback, along with a near complete lack of extras and complex mise-en-scene* shots, contributes to the feeling of a theatre play adapted for TV. Written by noted (well, he was noted in the '60s) cartoonist/writer Jules Feiffer it had in fact started out as a stage project, and maybe it should have stayed that way too. The first thing that may strike a modern viewer is how good an actor Art Garfunkel is. He goes up against a Jack Nicholson fresh out of Five Easy Pieces and holds his own ground, particularly in the opening half of the movie where his role is given most screen time. As the story and characters age, Nicholson's seemingly more troubled protagonist gradually takes over, and in a sense Carnal Knowledge betrays its initial promise of a chamber play and becomes another 'Jack' vehicle instead. And Nicholson is quite good, of course, particularly in the increasingly despairing scenes he shares with Ann-Margret, who does a very good acting job in addition to her Swedish bomb-shell looks. The talented couple basically hijack the last reel and turns Carnal Knowledge into a watchable relationship movie that finds Nichols revisiting the razorsharp domestic scenes of his debut Who's Afraid Of Virginia Woolf? (1966). However, this household purgatory makes for a different movie than the one which began with two young college friends who secretly dated the same girl, an interesting premise that is never mentioned or referenced in the later parts of the film. It's unclear whether Nichols, and maybe Feiffer too, knew exactly what the point was with the storyline as it unfolds over some 20 years; a feeling you never get with Five Easy Pieces, as an example. The viewer may be tempted to think that director and producer observed that most of the substance of the third reel was in the domestic Woolf dialogue and Nicholson's performance, and let that take over while sacrificing the dual or even quadruple balance indicated in the exposition. I don't particularly care about the 'message' or 'politics' of a movie as these things are subjective between different persons and also bound to change over time, but Carnal Knowledge, despite its seemingly liberated and self-assured female characters, has a rather unpleasant tone of patriarchal smugness about it. All the women, and ultimately Garfunkel's loyal friend, are reduced to mirrors for Nicholson's increasingly pathetic womanizer. The script tries to work around its inability to show his falling apart by invoking a theme of impotency, a cliché as tired as there is, and one which also brings sympathy to the character and reduces the chances for credible psychological demasking even more. It's all rather clumsily done, and I suspect the editing made it worse. Nichols seems influenced by the gritty realism of the New Hollywood yet misses two vital ingredients from the style, which is a sense of memorable cinema (not filmed theatre) in images and sets, and a striving towards originality and unpredictability in the storyline. The end result is simply a pretty dull affair, a mediocre made-for-TV drama with an unpleasant aftertaste, memorable mostly for a performance from Jack Nicholson which oddly both improves and damages the movie. The guys over at Cinefiles referred to Mike Nichols as a director who made a couple of good movies long ago which carried his entire career. Seeing Carnal Knowledge in 2013 seems to validate the remark. 5/10

*'Mise en scene', as used here at the Reflections, refers specifically to complex, choreographed shots that involve several people, a heterogenous setting (such as a plaza), and movements. The term is notoriously vague, but this narrow definition is how I was taught it long ago, and I find it useful.

Posted by Patrick at Lysergia

at 9:33 PM MEST

Updated: 7 October 2013 10:11 PM MEST

Across The Universe (2007)

Now Playing: tinnitus

Topic: A