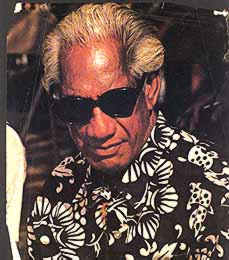

Legendary Hawaiian Surfer

Duke Paoa Kahanamoku (1880-1968)

"Mahape a ale wala'ua," Duke would say. "Don't talk -- keep it in your heart."

"Out of the water I am nothing"-- Duke

"Duke attained his greatest surfing satisfactions and some of his greatest achievements as a rider after his 40th year."-- Tom Blake

"Why not honor a living monument?"-- Arthur Godfrey

"My boys and I, we showed 'em how to go surfing."-- Duke, speaking about the Mainland Surfari of the Duke Surf Team

"Duke was Duke. His values came from the sea. He walked through a Western world, but he was always essentially Hawaiian. And because of the simplicity and purity of that value system, money was never that important to him."-- Kenneth Brown

"Duke was not in the business of being a beachboy. But in the larger sense of the word -- of a man who lived and loved the ocean lifestyle -- Duke was, as far as I'm concerned, the ultimate beachboy." -- Fred Hemmings

"He had an inner tranquillity. It was as if he knew something we didn't know. He had a tremendous amount of simple integrity. Unassailable in integrity. You rarely meet people who don't have some persona they assume to cope with things. But Duke was completely transparent. No phoniness. People could say to you that Duke was simple -- the bugga must be dumb! No way. That's an easy way of explaining that. Duke was totally without guile. He knew a lot of things. He just knew 'em." --

During the first half of the Twentieth Century, Duke Paoa Kahinu Mokoe Hulikohola Kahanamoku -- known to most of the world as Duke or The Duke, and to his long-time Hawaiian Islands friends as Paoa -- "emerged as the world's consummate waterman, its fastest swimmer and foremost surfer, the first truly famousbeach boy," wrote one of Duke's biographers, Grady Timmons. "He was a great chief of our time," Joseph Brennan -- the man who helped Duke with hisautobiography -- wrote, "indisputably the alii nui of Waikiki."

Duke Kahanamoku is best known to surfers as, "The Father of Modern Surfing." He was the foremost of the revivalists, bringing surfing back from near extinction at the start of the new millennium. A champion swimmer, Duke's life was crowned in Olympic glory and throughout his life, he was wave riding'sinternational ambassador. As a testimony of Duke's importance to the sport, one of his early surfboards, -- his 10-foot redwood board built in 1910, with his name across the bow -- is preserved in the Bishop Museum in Honolulu, on O`ahu.

Descendant of the Ali`i

Duke was born on August 24, 1890, "at Haleakala (the home of Princess Bernice Pauahi Paki Bishop)," wrote Joseph Brennan, "at King and Bishop Streets in Honolulu (where today the Bank of Honolulu is located), the same home where Duke senior had been born in 1869."

"At the corner of Kalia and John Ena Roads," Brennan continued, "at the Waikiki side of today's Wailana Apartments, two large, green-stained, Hawaiian-style cottages sat side by side. Trimmed in white, making them resemble houses at Waimea, these homes sat on a large grassy lot perhaps nearly an acre in size. Fromthem came and went the large families of the Kahanamokus and Paoas. Everyone in town knew these two homes. Side by side, they represented the best of`ohana living in those times." This was where Duke was raised.

As the eldest son, Duke was named after his father. His father was named "Duke" in July 1869, following an official visit to the islands from the Duke of Edinburgh, when some families named their sons after him. When Duke gained worldwide recognition for his Olympic swimming gold medals, there were attemptsmade to link him to royalty, because of his name. Duke would always humbly reply, "My father is a policeman."

Yet, Duke's family line is traceable to the royal Hawaiian line of ali'i. Duke, wrote Grady Timmons, was related by blood to Bernice Pauahi Paki Bishop, "the last of the Kamehamehas." And, as Joseph Brennan points out, "The Paoa-Kahanamoku house lot claim can be traced in the records as far back as 1847. NamingQueen Ka`ahumanu as the ali`i who placed the Paoa family on their house lot leaves little doubt that a connection existed between the 'Dowager Queen'Ka`ahumanu and earlier members of the Paoa-Kahanamoku families."

The time of Duke's birth "was a time of great unrest in Hawai`i," noted Brennan. "King David Kalakaua was in disfavor with many of his people. Certain segments of the populace -- the sugar interests, for example -- sought drastic changes. Island politics were in a state of flux. The King's sudden death in January of 1891 during his San Francisco visit proved to be the catalyst. Lili`uokalani, his sister, fell heir to rulership of Hawai`i. Her reign lasted but briefly; her abdication wasimmediately sought by dissenters. By 1893 she was ousted in a coup that is - to this day - vigorously contended by Hawaiian nationalists. The last Hawaiianmonarch, Lili`uokalani lost her throne to powerful commercial factions supported by the U.S. Navy. Sanford Ballard Dole became president of the islands'Provisional Government in the process. Little Duke was not quite four years old at the time, too young to know that history was being made and foreign nationalswere taking over the stewardship of his homeland.

"Hawai`i became a Republic on July 4, 1894, presided over by President Dole as Chief Executive. By July 7, 1898, when Duke was eight years old, the American flag flew over the Hawaiian islands. It was then that Duke first tasted wave riding.

"I was about 8 years old," Duke recalled years later, "when I started here at Waikiki Beach. That was a long time ago. We had nobody here to teach us how to ride these waves. We had to learn ourselves."

"As a matter of fact," Duke told SURFER magazine in the mid-1960s, "we even had to learn by ourselves, especially the surfboarding."

Two years later, on April 30, 1900, the Organic Act made young Duke an American citizen."

Barefoot Freedom

Duke was baptized in the ocean according to ancient custom. He "was among the last of the old Hawaiians, raised next to the ocean at Waikiki," wrote Timmons. At one point, early in his early boyhood, his father and uncle took him out in an outrigger canoe and threw him into the surf. "It was swim or else," Duke laterrecalled. "That's the way the old Hawaiians did it." Duke and his brothers were encouraged by both parents and, no doubt, other relatives as well. His brother Sargent remembered, "Mother used to tell her children, 'Go out as far as you want. Never be afraid in the water.'"

Waikiki Grammar School was located directly across from the beach. After school, the only logical thing for the kids to do was hit the water. Attending the school along with Duke were his sister and five brothers; Sam, Dave, Billy, Louis and Sargent. "All we did was water, water, water," Louis remembered. "My familybelieves we come from the ocean. And that's where we're going back."

"Waikiki of yesteryear had not been touched by today's tourism and commercialism," wrote Brennan, "so the oldtime values still held. Pure Hawaiians like the Kahanamoku's lived as though tomorrow held no threat and life was lived and enjoyed on a day-by-day basis. Meeting on the beach near the old Moana pier atWaikiki Beach was a daily routine for Duke, his brothers and their friends. When they were not in or on the water, there was always the strumming of `ukulele or guitars. Hours of 'talk-story' and laughter embellished their time away from school. At the harbor they dove for coins tossed by passengers on visiting steamers.Utopia and cash were theirs for the taking, and they revelled in it."

In true beach tradition, Duke and his brothers favored the bare foot over the shod. Joseph Brennan, in his DUKE: The Life Story of Hawai`i's Duke Kahanamoku, wrote: "one story tells how the boys would leave the house wearing their shoes of stiff, squeaky leather -- only to yank them off and hide them in sand or bushes immediately on leaving sight of Mama. Mama felt that unshod feet did not become sons of an officer of the law. Out of sight, the boys reveled intheir barefoot freedom, but on returning home, they always retrieved and donned shoes before entering the house. Duke grinned when telling how their father always knew of their trick, but simply acted ignorant as they came squeak-squeaking across the floors. Father, too, had once been a boy who loved the oldbarefoot Hawaiian ways."

Under the Hau Tree

In his teens, Duke dropped out of high school and took up the life of a beachboy. Beach boys were locals who worked and hung out in the beach environment of Waikiki, putting on exhibitions, taking tourists for rides, renting beach gear, etc. Gathering daily with other young beach boys by a hau tree at Waikiki, Duke entered a lifestyle that fell naturally to him. They surfed, canoed, swam, repaired nets, shaped surfboards, played `ukelele and sang. This group of beach boys was the nucleus of what later became the Hui Nalu, one of the very first Hawaiian surf clubs.

In the mid-1960s, SURFER magazine asked Duke how the Hui Nalu had first gotten its name.

"A group of us surfers used to be sitting about the beach under the hau tree close to the Moana Bath House. Well, the name Hui Nalu was picked up between Knute Cottrell and I when we were out surfing one day. We were out there sitting and watching for surf to come in and, of course, as you know now, they come in on sets; some one, three, five and seven. Well, we were sitting there looking and we thought, gee, if we only can form a club and this would be the world - Hui Nalu - because 'hui' is 'to get together' - or 'organization', or something like that - and 'nalu' is 'surf', so that's how we got the name Hui Nalu.

"And when we started together there was Knute Cottrell [and] a lot of the boys. The Hustace boys were there, too, and Harold Castle and Eddie Holt and all those fellows who used to be out there surfing, riding the surfboards."

As the best waterman among the formidable group of young watermen at Waikiki, Duke became the group's leader. He set a good example. He didn't drink or smoke and if he did get into a fight, it was after being hassled, and even then he would not punch, preferring to slap, instead. He seldom raised his voice. He used his eyes to communicate what he didn't vocalize.

Years of surfing, rough-water swimming and canoe paddling as a boy and then as a young man molded Duke Kahanamoku into a superb athlete. "He had glistening white teeth, dark shining eyes, and a black mane of hair that he liked to toss about in the surf," wrote Timmons. "He stood six feet one and weighed190 pounds. He had long sinewy arms and powerful legs. He had the well-defined upper body that all great watermen possess, his 'full-sail' shoulders taperingdown to a slim waist and a torso that was 'whipcord' tight."

As impressive as the rest of his body was, his hands and feet were extraordinary. A veteran Outrigger Canoe Club member remembered that Duke's hands were so large that when he scooped up ocean water and threw it at you in fun, it looked like a whole bucket of water coming your way. "He could cradle water in his hands, cupping it between his palms, and just shoot a fountain at you. It came with great force. He would often cross his hands in the water -- slapping thesurface -- and it would just be boom! boom!"

Whether fact or fiction, some claimed Duke could steer a canoe with his feet alone. "He had fins for feet," declared legendary surfer Rabbit Kekai. "He didn't needa paddle."

Bigger Boards for Bigger Surf

Duke was among the few who dared ride Castle's, a primo surf spot at Waikiki, known for its size of waves on a good swell. When the surf was not particularly strong, he tore it up on the inside.

Surfing's resurgent popularity, at Waikiki during the first decade of the new century, "was at least partly due to Duke's flamboyant shows at Waikiki.," wrote Brennan. "His spectacular rides kept the tourists talking. Other surfers vied for the same attention, though few could match his skills.

"As Duke grew into strong, young manhood, he rode the waves the way he'd heard the ali`i warriors had ridden them -- proudly and handsomely. He began making the biggest boards to ride the tallest waves. Peers who shared the surfing with him strove to copy his finesse..."

An expression heard the most, when he caught a wave, was his yell of "Coming down!"

"Duke was never afraid of anything in the sea," recalled Kenneth Brown, a prominent part-Hawaiian who sailed the turbulent inter-island channels with Duke. They often sailed to the Kona Coast, on the Big Island, where Brown had spent part of his youth. "Duke reminded me of many of the Hawaiians I had met there. Their sense of their environment was unusual. They didn't differentiate much between what was above and below the sea. They had place names for all the hills and bays like we do, but they also had place names for things down in the water. That's the way it was with Duke. The ocean was such a familiar, friendly environment for him. He was no more afraid of what might happen to him at sea than you or I would be of getting hit by a car crossing the street. The ocean was his home."

Duke favored traditional Hawaiian customs and manners. He spoke Hawaiian as much as he could, preferred Hawaiian foods like poi and lau-lau (fish), and saw more in the old Hawaiian surfboard and canoe designs than most anyone else of his time.

In his youth, he was perhaps stricter about the traditional designs than he would later become. There's this story about a surfer nicknamed "Mongoose," who sharpened the rounded nose of his board so that he could more easily cut left and right across wave faces. Duke watched from a distance, disapproving, butsaying nothing. One day, when Mongoose's pointed-nose board was left unattended, Duke "liberated" it and sawed off the nose altogether.

Yet, Duke declared that even while he was still attending school, "I was fired up with a mania for improving the boards and getting the most out of the surf. I was constantly redoing my board, giving it a new shape, new contours, new balance. Others, too, began building new boards and experimenting in various ways.Everyone wanted to outdo the other. Apparently my enthusiasm was catching. No one was content to simply come up with the best possible board; everyonewanted to excel as a surfer -- and the rivalry was keen. I, for one, spent countless hours working at every phase of controlling my boards in the waves, trying new approaches, developing new tricks. When I wasn't at school, I was in the surf."

It was in the period of 1909-10, that Duke began to get others interested in longer alaia style surfboards. No one besides Duke, apparently, ever got into the even longer olo-type boards until Tom Blake came to the Islands in the mid-1920s. "They grew from eight to nine feet or so," wrote Blake, in his book Hawaiian Surfboard, published in 1935. "Duke's new one being ten feet long and three inches thick."

Duke raised board surfing's performance level with his new board - about 2 feet bigger than the day's standard. It was made of redwood, 10 feet long, 3 inches thick, 23 inches wide and weighing 70 pounds. Built in 1910, this board, with Duke's name scrolled across the top, near the nose, soon became the standard and was still in vogue by 1935 when Blake's hollow boards began to take over.

"Riding the Surfboard," Mid-Pacific magazine, February 1911

In the premier issue of Mid-Pacific magazine, February 1911, Duke wrote a front page article on surfing: "I have never seen snow and do not know what winter means. I have never coasted down a hill of frozen rain, but every day of the year where the water is 76, day and night, and the waves roll high, I take my sled, without runners, and coast down the face of the big waves that roll in at Waikiki. How would you like to stand like a god before the crest of a monster billow, always rushing to the bottom of a hill and never reaching its base, and to come rushing in for a half a mile at express speed, in graceful attitude, of course, until you reach the beach and step easily from the wave to the strand?"

"Kahanamoku," wrote surf journalist Matt Warshaw, "then 21, a part-time stevedore, was first among equals with the Waikiki set - no small honor for a surfer."

Freestyle Records Broken, August 11, 1911

When Duke surfed, he made surfboards slide across wave faces without the -- as yet to be invented -- skeg. When he swam, his "Kahanamoku kick" was so powerful that his body actually rose up out of the water, "like a speed boat with its prow up," boasted his brother Sargent.

The first time Sargent Kahanamoku had really watched his brother swim for speed was at the Waikiki Natatorium, a salt-water swimming pool located on Diamond Head's flank. The old timers told Sargent to watch his brother, that when he swam he created waves. When Duke swam there, Sargent saw the waves spread outand hit the sides of the pool. "And I mean they were big," he said, adding with exaggeration, "so big that it seemed like they could be ridden with a surfboard."

During the summer of 1911, Duke Kahanamoku was on, "one of his daily swims off Sans Souci Beach at Diamond Head when he was clocked in the 100-yard sprint by attorney William T. Rawlins, the man who was to become his first coach," wrote Grady Timmons, adding it was Rawlins who encouraged Duke and hisbeachboy friends to form the Hui Nalu and to enter the first sanctioned Hawaiian Amateur Athletic Union swimming and diving championships.

These were held on August 11, 1911, where, in "the still, glassy waters of Honolulu Harbor, at age twenty-one," Duke Kahanamoku, "swam the 100-yard freestyle 4.6 seconds faster than anyone had before him." Duke did the 100-yard freestyle in 55.4 seconds, "shattering the world record held by [two time] U.S. Olympicchampion Charles M. Daniels." In the process, he had put a 30-foot gap between himself and the runner-up. Less than an hour later, Duke equaled Daniels' worldrecord in the 50-yard freestyle, coming in at 24.2 seconds. For extra measure, Duke outswam all competitors with a respectable 2:42:4 second finish in the 220-yard freestyle event. Hui Nalu swept eleven events.

Results of the meet were telegraphed to the Amateur Athletic Union headquarters in New York. The official reaction was one of disbelief. An unknown 21 year-old Hawaiian shattering the world's most important swimming record? Even more unbelievable was that Duke had not only shattered the record, he haddone it in Honolulu Harbor salt water, "on a straightaway course," wrote Leonard Lueras in his book Surfing: The Ultimate Pleasure, "that stretched from a barnacled old barge into what was called the Alakea Slip, a moorage between Piers 6 and 7. A thick rope was stretched taut over the water to mark the finish line. A 55.4 seconds showing in the 100-yard sprint? In a murky, flotsam-filled harbor? Between two ships' piers? I mean, really folks?"

The AAU officials sent back their reply: "What are you using for stop watches? Alarm clocks?!"

Next day, The Honolulu Advertiser proclaimed: "Duke Kahanamoku Broke Two Swimming Records. Hawaiian Youth Astounds People By The Way He Tore Through The Water." Duke was referred to as the expert natatorial member of the Hui Nalu club. "Kahanamoku," the article went on to predict, "is a wonder, andhe would astonish the mainland aquatic spots if he made a trip to the coast." Later, Honolulu sports columnists would joke that Duke's "luau feet" were so big(size 13), it was their size that propelled him through the water.

Despite the fact that the swim had been clocked by five certified judges and the course measured four times, once by a professional surveyor, Duke's accomplishment was not officially recognized by the Amateur Athletic Union. AAU officials argued that Duke's record-breaking swims must have been aided bya current in the harbor. Although the AAU would retract their original decision years later, the original decision delayed Duke's rightful recognition.

Even though officials and fans in Hawai`i were bummed, the decision against him didn't phase the Duke. He just went back into training. Years later, he told a reporter that he was able to swim so fast in Honolulu Harbor because, "Our water is so full of life, it's the fastest water in the world. That's all there is to it."

The Kahanamoku Kick Overseas, 1912

With money raised by the Hui Nalu, Duke went to the Mainland the next year. Throughout 1912, he delighted sports fans with his swimming technique learned from Australian swimmers who had visited Hawai`i in 1910. What sportswriters would refer to as "the Kahanamoku Kick," was actually Duke's adaptation of the Australian Crawl. It was a crawl stroke with scissoring feet and the addition of a "flutter kick."

Once Duke got used to the colder water of the Mainland, he began to astound audiences. Sports fans began to call him "The Human Fish" and "The Bronze Duke of Waikiki." After warm-up meets in Chicago and Pittsburgh, among other places, Duke competed in an Olympic trials swimming meet held in May 1912, in Philadelphia. He qualified for the U.S. Olympic team by winning the 100-meter freestyle event in exactly 60 seconds.

Less than a month later, at Verona Lake, N.J., Duke qualified for the U.S. Olympic 800-meter relay team. More importantly, during his 200-meter test heat, he bettered the existing world record in the 200-meter freestyle held by Charles M. Daniels. Although Duke wasn't considered a middle distance swimmer, hebettered Daniels' 200 meter record by six-tenths of a second. His time: 2:40:0. A New York World reporter wrote that Duke began with an "unconcerned" start,"and it was fully two seconds before he went after the field. Once in the water, he quickly overhauled his opponents."

The 1912 Olympics, Stockholm, Sweden

On his way to the 1912 Olympiad in Stockholm, Sweden, Duke met native American Jim Thorpe, celebrated as the greatest all-around athlete of his time. "When Jimmy and I were on the boat to the Olympics in Sweden," Duke remembered, "we had a talk. I said, 'Jimmy, I've seen you run, jump, throw things and carry the ball. You do everything so why don't you swim too?'

"Jimmy just grinned at me with that big grin he had for everyone, and said, 'Duke, I saved that for you to take care of. I saved that for you.'"

Sports history was made in Stockholm. Jim Thorpe won almost everything on land and Duke Paoa Kahanamoku won almost everything in the water. Duke broke the record for the 100-yard freestyle, winning the gold medal. Another legendary surfer, George Freeth, had been disqualified from the Olympic trials, back in theStates, because his job as lifeguard was considered a professional position.

Kahanamoku and Thorpe so impressed their Swedish hosts and the world that both were personally called to the Royal Victory Stand where they received their gold medals and Olympic wreaths directly from Sweden's King Gustaf. Years later, in 1965 at age 75, Duke reminisced about the triumphant moment 53 yearsearlier. "Come here. Come here a minute. Let me show you something," Duke said. His interviewer wrote that his "now cloudy eyes became clear and his haltingspeech fluent as he fondly handled a framed wreath on his bedroom wall.

"'I was just a big dumb kid when King Gustaf of Sweden gave me this. I didn't even know what it was really and almost threw it away. But now it is my most prized trophy,' he said proudly."

Even "before the Games were finished," Matt Warshaw wrote, "Kahanamoku, through style and presence as much as athleticism, had become a European sensation. It helped that 'Duke' often registered in the Old World as a title rather than a given name, allowing him an up-front measure of deference and respect.And even if Kahanamoku was a nearly inarticulate ninth-grade dropout, he did in fact have a noble bearing. He could look dignified even as he hunched his 6-foot, 2-inch, 183-pound frame around a tiny wooden ukelele between races at Stockholm, his giant hands strumming casually. Outside the arena, he dressed likean Oxford graduate in a tailored suit, high-collared dress shirt, and silk tie. The case may have been overstated when Kahanamoku was described by an Americansculptor as 'the most magnificent human male that God ever put on the earth,' but he was attractive by any standard - powerful, gentle, and exotic, with high, slanting cheekbones, dark eyes, and a wide, full-lipped mouth. He had a calming presence. His biggest smile, rarely practiced, sent out near-visible waves of kindness and warmth."

On the way back from the 1912 Olympics, Duke decided to take a swim in the middle of the Atlantic. Warshaw tells the tale:

"In 1912, when the steamer New York had some engine trouble and stalled in the middle of the Atlantic, Kahanamoku put on his bathing suit and jumped over the railing for a swim. The ship quickly drifted away on the current, and a lifeboat had to be sent out to rescue the Olympic hero."

When he returned to the United States after several months in Europe, "The Swimming Duke" was both respectfully besieged by adoring fans and reporters wherever he went and also discriminated against.

When Duke returned to Honolulu, he was met by the Royal Hawaiian Band. They played in his honor and cannons were fired in salute. "Elsewhere," noted Warshaw, "the reception hadn't been nearly so welcoming. Skin color had been an issue during Kahanamoku's travels, especially through continental America.He was refused service by restaurant owners. His Polynesian features often stumped the provincials, as they tried to figure out whether to slander him as a black man or as and Indian. The sporting press, meanwhile, still overlooked him in favor of George Cunha, Kahanamoku's friend and teammate - who was referred to inprint as 'the world's finest white sprint swimmer.'"

"In the course of the next twenty years," wrote Grady Timmons, Duke "continued to defy time, competing in four Olympic Games and winning five medals. When he finally retired, at age forty-two, he could still swim as fast as when he was twenty-one."

1st Surfing on the East Coast, 1912

On his way back from the Olympics, Duke stopped at the University of Pennsylvania, where he had trained for Stockholm. While there, he made a trip to the Jersey Shore and put on demonstrations of swimming and surfing at Atlantic City, and board and body surfing in Nassau County, Long Island, New York.

Clair Tait, a native of Portland, Oregon, was in the Navy and stationed at Pearl Harbor. Tait was a "particularly fine fancy diver," had held the Pacific Coast diving championship, and was now trainer for the tour. He reported to the press on Duke's board riding and their bodysurfing in the waters off Long Island's SouthShore:

"You should have seen us stage an exhibit at Castles by the Sea, the Long Island resort started by Vernon Castle. A big storm was on and the lifeguards kept everybody from going out except we fellows from Honolulu. Duke took a surfboard out to the last line of breakers, half a mile out, and rode all the way in at express-train speed. The waves were the best ever seen. We gave people something new in the line of body surfing when we rode the crest of the waves for 200 and 300 yards. The shore was lined with enthusiastic people and we were nearly mobbed when we started back for the dressing rooms. There were cameras by the hundreds, and Duke was photographed until he was blue in the face."

Duke recalled much later in his life that he did not board surf on Long Island the first time he was on the East Coast. "I did bodysurf there [in New York, on Long Island] -- Far Rockaway and Sea Gate and places like that. But the boards - I never had a chance to carry a board or anything like that... in 1912, after I came back from the Olympics... in Stockholm. I came back to Philadelphia... I was training there with George Kistler of the University of Pennsylvania... I came back and then I went over to Atlantic City and rode the board there (laughs) and the water was, well - the water was all right. And then I... [took] that doggone board. I'd carry it on the pier and then throw it off the pier. And, you know, those piers down at Atlantic City there [are] very high. I used to chuck this doggone surfboardoff the pier and into the water and then jump or dive and picked up the board and then ride them by the side of the pier."

More Than A Beach Boy

After the Stockholm Olympic Games, Duke swam in exhibitions and swimming meets throughout Europe and the United States. It was while on tour that he began to demonstrate not only his swimming, but his surfing as well. In 1912, he surfed for crowds of people in places like George Freeth's stomping grounds of Balboa Beach and Corona del Mar, in Southern California.

Duke returned to Hawai`i a conquering hero. Inside, however, was a growing insecurity, the kind every aging surfer gets sooner or later. "Here he was, twenty-two years old, and the only thing he knew was the ocean. After the celebration came to an end, he had to ask himself: what am I returning home to?"

"He could only find menial work in Honolulu," Matt Warshaw wrote, "and in late 1912, just weeks after being feted in one European capital city after another, he was working as a meter reader on Honolulu city streets. Perhaps Hawaii didn't owe him a job," Warshaw argued. "But nonetheless there seemed to be a moraland financial imbalence when local officials, the Chamber of Commerce, and the Hawaii Promotion Committee all acknowledged Kahanamoku's part in makingHawaii one of the world's premier tourist destinations, then refused to cut him in on the proceeds. Yet Kahanamoku never lost his sense of obligation to his home state. For decades he served as a Honolulu city greeter and escort. Babe Ruth, Shirley Temple, Mickey Rooney, Groucho Marx, Prince Edward, ArthurGodfrey, and President Kennedy - all were met and squired by Kahanamoku when visiting Hawaii, and all were touched by his gracious, playful, definitive alohastyle. When the British Queen Mother arrived in Honolulu in 1966, she accepted a flower lei from the white-haired surfer as Hawaiian music played in thebackground, and moments later the two began an impromptu hula."

Duke tried getting "real jobs". In addition to the water meter reading gig, he tried working in the drafting office of the Territorial government, pumping gas, and surveying -- amongst others. In none of them could he find his place. At other times, he was forced to take very lowly positions like sweeping the floors andmowing the lawns of City Hall. "On and off for many years," wrote Grady Timmons, perhaps not quite on the mark, "he even tried being a beachboy, only to find there was not much money or dignity in it for a man of his stature."

Being a beachboy "helped him stay in shape," wrote Joseph Brennan. "Saturdays, Sundays, and holidays he helped with the outrigger canoes at the beach hotels. It didn't pay much, but every dollar was important. With his power and boat sense he was often the steersman... He picked up odd dollars here and there by teaching tourists to surf and swim...

"Duke found it rough, being a big star yet having such little income. He was a grown man, recently returned from being dined and wined like royalty. It was a bitter pill to settle for a meter reader's routine or an office boy's pay. Trying to adjust left him confused and bewildered. He continued to flounder, trying to scrounge out a living."

"What made it even worse," continued Brennan, "was that, with his fame and good looks he was an outstanding attraction to women on the beach. The paradox was that he could not afford to take out the very lovelies who made such a fuss over him. He was too proud to let them pay. There were moneyed female tourists, including visiting heiresses and well-to-do kama`aina women who sought his companionship. It humiliated him to realize just how insignificant his income was...

"In his Hawaiian way, he reminded himself that there are two lives for each of us -- an outer one of action and an inner one of the heart and mind. He recognized that one can always see a man's deeds and outward character, but not the inner self. There was always that secret part to everyone that had its own life,unpenetrated and unguessed by others. In that secret life Duke quietly rebelled at being a celebrity without funds. He was celebrated and honored, but withoutthe ability to hold up his own end."

It was only after accepting invitations to compete abroad in exhibition swimming meets that Duke found a place and a role that fit him, as the unofficial ambassador for Hawai`i and Hawaiian water sports -- especially surfing. Travel was something Duke liked; it kept him active and in the water. Whenever hecould, he combined his swimming with surfing demonstrations.

Hawai`i's Ambassador

Duke has been credited, and rightfully so, as the man who introduced surfing and Hawai`i to the world. "At that time," noted Timmons, "Hawaii was the last outpost of the United States. It was the most isolated spot on earth, farther away from any place than any other place in the world. And then along came Duke, shoring up that distance with a single, powerful swimming stroke, emerging onto the world stage as if he had just stepped off his surfboard."

George Freeth had been the first to introduce surfing to mainland USA, with his professional surfing at Redondo Beach, beginning in 1907. But, it was Duke's highly publicized exhibitions on the West Coast that really grabbed people's attention. Soon, dedicated Mainland surfers were emerging primarily in Southern California, "catching the waveriding bug," after Duke's trailblazing in 1912 and again in 1916.

While giving the surfing demos, Duke Kahanamoku caught the eye of Hollywood. Soon, he was asked to play parts in early films being produced there. Between his Olympic triumphs of 1912 and 1920, he thus became a supporting actor and began a minor career as an extra in Hollywood. As early as 1913, he was hanging out with the Hollywood crowd during the week and taking selected new friends surfing on the weekends.

Duke was in and out of Los Angeles for the next 20 years. "I played chiefs -- Polynesian chiefs, Aztec chiefs, Indian chiefs... all kinds of chiefs," he once said. He also played parts as "a Hindu thief and an Arab prince." It wasn't until 1948 that he got a Polynesian part. He was Ua Nuka, or "the Big Rain," and he was cast opposite John "Duke" Wayne in the movie, The Wake of the Red Witch.

During these years, Duke's fame spread. In 1915, he took his swimming and surfing skills to Australia, where he, "literallypushed that great sea-oriented country into surfing," wrote Lueras. His surfing at Freshwater, January 15, 1915, is legendary and his impact on Australian surfing is immense.

Duke Surfs Freshwater, December 24, 1914

In 1912, well-known Australian swimmer, local businessman and politician Charles D. Paterson, of Manly Beach, Sydney, had brought a solid, heavy redwood board back with him from Hawai`i. He and some local bodysurfers tried to ride it, but with little success. "When he and his mates couldn't figure out how to ride it," freelance writer Sandra Hall wrote, "his wife used it as an ironing board." So, it was not until Duke visited Australia in 1914-15 that true board surfing hit theAussie shore.

In 1914, would-be surfer and writer Cecil Healy primed Australians with the possibility of Duke Kahanamoku coming to Australia to show a thing or two.

"Sportsmen everywhere," wrote surf journalist Matt Warshaw in 1997, "recognized the pure-blooded Hawaiian not just as the fastest swimmer alive and an Olympic gold-medal winner but as an international celebrity. Many also knew him as the world's greatest exemplar of the newly revived sport of surfing - or 'board-shooting', as the Australian press called it. Kahanamoku, whose self-confidence was faulty at best, tended to view himself as little more than a gypsy son of Waikiki."

"Kahanamoku is a wonderfully dexterous performer on the surfboard," wrote Cecil Healy, "an instrument of pleasure that Australians have so far been unsuccessful in handling to any degree. Reports have been brought back from overseas of his acrobatic feats exexuted while dashing shorewards at greatspeeds, but one doubts the possibility of Duke, or anyone else, duplicating such feats in Australian surf. Still, if he should give one of his rare exhibitions for ouredification, be sure it will create a keen desire on the part of our ambitious shooters to emulate his deeds, and it goes without saying that his movements will be watched intently. Personally, I am convinced that the natural amphibious attitude of the Australians will enable one or another to unravel the knack."

The New South Wales Swimming Association invited Duke Kahanamoku to give a swimming exhibition at the Domain Baths, in Sydney, as part of a 33-race swimming tour. "The country had been at war with Germany since the preceding summer," wrote Duke's biographer Joseph Brennan, "and people needed a lift.Duke proceeded to furnish it." The Hawaiian arrived in Australia 0n December 14, 1914.

"Kahanamoku arrived in Sydney on December 14 after a 2-week boat trip," wrote Matt Warshaw, "and a few days later agreed, when asked by local swimming organizers, to give a surfing demonstration.

In essence, it was Duke who brought surfboard riding to the Australian continent. The "Bronzed Islander" was subsequently the catalyst for the entire surfing movement that would later emerge in Australia.

Yet, Duke's surfing in Oz was problematic at the beginning. He had not brought along a surfboard. That did not quash the deal. He just made one. "Duke was invited by Cecil Healy's friends," wrote Sandra Hall, "to spend Christmas at Freshwater Beach, a cozy, protected beach with camping huts... While staying there,Duke fashioned a surfboard from pine."

Patricia Gilmore, an Australian reporter/historian, described what happened, in a nostalgic look back for The Sydney Morning Herald, in 1948:

"Having no board, he picked out some sugar pine from George Hudson's, and made one. This board -- which is now in the proud possession of Claude West -- was eight feet six inches long, and concave underneath. Veterans of the waves contend that Duke purposely made the surfboard concave instead of convex to give him greater stability in our rougher (as compared with Hawaiian) surf.

"Duke Kahanamoku was asked to select the beach where the exhibition would be given. He chose Freshwater (now Harbord)," on Sydney's north side, to give his initial demonstration on surfboard riding. "I was in Australia long enough," he explained, "to build a makeshift surfboard out of sugar pine." Duke didn't know about C.D. Paterson's redwood board in the district, so he made his own out of "a piece of sugar pine supplied by a surf club member whose family was in the timber business."

Varying dates are given for Duke's Australian surfing demonstration. That is perhaps because he made more than one. According to the Sydney Morning Herald of December 25, 1914, it was the previous day - December 24, 1914 that Duke first rode Aussie waters.

Nat Young recreates that historic three hour demonstration, based on a conversation he had with Isabel Letham, the woman whom Duke rode tandem with that day. It was "A clear, brilliant day. Spectators were milling around to watch. Manly Surf Boat was on hand to give Duke assistance to drag his board through the break -- an offer he laughed at good naturedly. Picking up his board he ran to the water's edge, slid on and paddled out through the breakers. He made better timeon the way out than the local swimmers who escorted him. Once out beyond the break it wasn't long before he picked up a wave in the northern corner, stood upand ran the board diagonally across the bay, continually beating the break."

"Kahanamoku entered the water with the board," according to the Sydney Morning Herald, "accompanied by Mr. W. W. Hill and some members of the Freshwater Surf Club. Lying flat on the board and using his arms like paddles the champion soon left the swimmers far behind. When he was about 400 yards out he waited for a suitable breaker, swung the board round, and came in with it. Once fairly started, Kahanamoku knelt on the board, and then stood straight up, the nose of the board being well out of the water... On a couple of occasions he managed to shoot fully 100 yards..."

"The Wednesday morning surf check found some passable waves at Freshwater," Matt Warshaw put it another way. "By 10:00 A.M. the summer sun had warmed the beach, and two or three hundred spectators were lined up along the shoreline, with dozens more settled in on the nearby headland. Kahanamokuarrived at 10:30. He moved across the sand toward the ocean in a standard black, one-piece swimsuit, with his new board resting easily on his right shoulder.Members of the local surf-rescue club, in a sincere but countrified offer, said they'd tow his board through the waves in their surfboat. Kahanamoku said he could manage. The lifesavers nonetheless trailed Kahanamoku as he walked across the wet sand into the surf. Seconds later, paddling through the lines ofbroken waves, he distanced himself from the local convoy and soon pulled up alone in the calm water outside the surf line. He sat on his board and watched the ocean for a few moments. A swell moved in. He rotated to face shoreward, went prone, paddled, waited as his forward movement was amplified by the wave'senergy, then pushed to his feet. New board, new spot, first time surfing in a month - Kahanamoku set an easy course to his left and simply let the wave push him into shallow water."

"It was Kahanamoku's first attempt at surf-board riding in Australia," printed the Sydney Morning Herald the next day, "and it must be admitted it was wonderfully clever. The conditions were against good surf-board riding. The waves were of the 'dumping' order and followed closely one on top of the other...Then, too, Kahanamoku was at a disadvantage with the board. It weighed almost 100lb. whereas the board he uses as a rule weighs close to 28lb. But, withal, he gave a magnificent display, which won the applause of the onlookers."

Duke showed the crowd everything in the book," 1960s surf champion Nat Young wrote, "from head stands to a finale of tandem surfing with a local girl, Isabel Letham."

"There was a big sea running," wrote Patricia Gilmore, "and from 10:30 in the morning until 1 o'clock Duke never left the water.

"He showed the watchers all the tricks he knew, sliding right across the beach on the face of a wave. Demonstrating the ease with which he could manage with a passenger, he took Isabel Letham (still a resident at Harbord) out with him, and they would come right into the beach with incomparable grace and precision."

His tandem partner was only 15 years old at the time. Isabel Letham was already a recognized and respected bodysurfer, aquaplanist and ocean swimmer. "When we got onto the crest of this wave," she recalled later, "and I looked down into the trough, I thought I was going over a cliff. Letham shouted for Duke to stop and he stepped back to stall. On another wave, Letham again resisted. On the third or fourth wave, Duke ignored her, pressed forward, stood and pulled Isabel toher feet and onto his shoulders. "After that," she said, "I was all right." After four waves of going tandem with Duke, Letham was "hooked for life," she recalled."It was the most thrilling sport of all."

While Duke went on tour Australia's eastern states, competing in swim meets, Isabel Letham practiced her surfing. When Duke returned to surf at Sydney's Dee Why Beach before returning to Hawai'i, she rode with him again, at an exhibition that was widely publicized. She was later inducted into the Australian Surfing Hall of Fame for the role she played in encouraging later Australian generations of women surfers.

Duke recalled to his biographer, in World of Surfing, "In 1915 the swimming-obsessed Aussies wanted to see the so-called 'Kahanamoku Kick,' so, along with several aquatic stars, I had the pleasure of visiting that wonderful land of Down Under. The swimming exhibitions went well and we were gratified over the royal treatment they gave us." While exhibition swimming at the Domain Baths, Duke broke his own world record for the 100 yards with a time of 53.8 seconds.

"When he went to Australia to show them surfing," Duke's brother Bill recalled, "the lifeguards tried to stop him. They said, 'You can't go out there. There are alot of man-eating sharks.' Duke said, 'Ah, no, I'll go out.'" After Duke's surfing exhibition, when he came back to the beach, "the lifeguards asked him, 'Did you see any sharks?' Duke said, 'Yeah, I saw plenty.' 'And they don't bother you?' the lifeguards asked. 'No.' Duke replied. 'and I didn't bother them.'"

"I must have put on a show that more than trapped their fancy, for the crowds on shore applauded me long and loud," recalled Duke. "There had been no way of knowing that they would go for it in the manner in which they did. I soared and glided, drifted and sideslipped, with that blending of flying and sailing which only experienced surfers can know and fully appreciate. The Aussies became instant converts."

Duke As Catalyst To Australian Surfing

While in Australia, Duke also made a tour of some of the beaches because he "was particularly excited by the fantastic surfing conditions they have down there."

Freddie Williams, sometimes known as the "Father of Australian Bodysurfing," went out with Duke on a number of surfing excursions to the beaches of Sydney. On one outing, he went out on the pine board with Duke at Manly Beach. His daughter, Marjorie Sirks recalled, "While they were waiting for a wave quite adistance from shore, to Freddie's horror, a shark's fin broke the surface. Duke just waggled his foot at its nose, the way you shoo a cat away."

Duke's impact on Australian surfing was tremendous. He essentially kick-started surfing in Oz. Over twenty years later, in 1939, on the eve of a big Pacific Aquatic Carnival held in Honolulu, then longtime surfboard champion of Australia, Snowy McAlister, wrote: "We in Australia learned the rudiments of the sportfrom Duke. He gave the boards new meanings. I don't think anybody, Hawaiian or Australian, could duplicate Duke's old time skill."

One instant convert was ten year-old Claude West, a Manly beach local. "He was so impressed by what Duke did that he managed to get the Hawaiian to coach him in the art of board riding, and when Duke left Australia he passed the board he had made on to the youngster. Claude soon became a proficient board rider, and other surfers began to imitate him. Claude proved himself a great surfer: he won the Australian surfing championships from 1919 to 1924."

Claude West went on to demonstrate the benefits of the surfboard in surf rescue work and at one point rescued the then Governor-General of Australia, Sir Ronald Munro Ferguson. He built many boards like the one Duke had given him and was a fine craftsman, "having learnt to fine-plane making coffins for anundertaker." In 1918, West attempted to make a lighter surfboard by chipping out the center of a solid board and covering it with a lighter wood. The experimentfailed, due to the absence of a waterproof glue, which had not been invented, yet, and the fact that all Australian timber of the period was sun-dried instead of kiln-dried. When the sun got to the board, it quickly cracked the thin outside veneer.

Before Duke had left Australia, in 1915, he also helped show the Aussies how to build boards. "Nothing would do," he recalled, "but that I must instruct them in board building -- a thing which I did with pleasure. Before I left that fabulous land, the Australians had already turned to making their own boards and practicing what I had shown them in the surf."

"Incidentally," added Duke, "forty years later, Tom Zahn came to Australia, found my sugarpine board to be still in seaworthy shape. He took it out into the waters of Freshwater Bay and gave the spectator-jammed beach an exciting surfing demonstration."

World War I

In the 1960s, Duke was asked about the number of people surfing on any given day at Waikiki in the 1915 timeframe. He answered:

"I don't think there would be more than 10 or 12; maybe a little more than that; maybe 20, but not any big number like you have today."

"Who were some of the great surfers with you in the old days?"

"My brother Sam, Louie, all of them, these kids who were riding," Duke recalled. "And the Hustace boys, about four or five of them. They used to ride them and they used to live right in front of the Canoe surf. And some other of the boys, like Harold Castle used to be out there. Eddie Holt and that bunch and some Hawaiian boys from over there by thestone wall... and Bill Kerr. There were so doggone many of those old timers... Knute Cottrell was one; Cooper was another boy; and Kenny Brown, we used to call Rusty; and Kenny Winter and, oh, so many..."

But none of the Waikiki beachboys and surf riders gained the notoriety or had the leadership of the scene like Duke did.

"Like many beachboys," wrote Joseph Brennan, "Duke took great pride in his surfboard and had his name on it. Since other surfers had begun to fashion boards designed like his, the name helped to distinguish his from the others. It was not publicity, it was just identification.

"It was not too long before visitors began asking to have their picture taken alongside Duke and his board. He smiled and obliged, though it all seemed silly. The beachboys he'd grown up with ribbed him and he couldn't help being self-conscious. It became a problem just to get his board off the beach and into the surf.Duke could not bring himself to refuse those who demanded his attention.

"The situation went from awkward to worse. One afternoon he left his surfboard leaning against the Moana Hotel pier pilings. Returning, he spotted a lady tourist standing prettily against the board while her girl friend snapped the picture. To compound the problem, others were standing along side, obviouslywaiting their turn. The sight stopped Duke cold. He retreated some distance, wondering when the sightseers would finish. They were casual and unhurried.

"The sea beckoned while the tourists posed. Shyness and heat drove Duke back up the beach. Seeing -- and reveling in -- his predicament one of the beachboys called out, 'Auwe, Paoa! Why you not surf, eh? Big waves out dere!'

"Duke looked back at the group clustered around his board. He grinned. 'To get that board now?' He shook his head, 'Waste time!'

"'How 'bout usin' mine?' one of the surfers volunteered.

"Duke flicked sweat from his forehead and glanced at the cooling sea. 'Why not? Thanks!' He walked over, accepted the board, and headed seaward." Next day, a photo of a curvaceous girl beside his surfboard appeared in the newspaper with the caption: "Tourists want picture with Duke's surfboard." Later, photographsof tourists with Duke and his board were used as promotions for tourism of Hawai`i.

Later on in life, Duke was asked about how bad elements at Waikiki were handled. Of course, the question to him was phrased differently and it's interesting to see that even Duke equated being a beach bum with being bad:

"Duke, back in your day, did you have the trouble we have now of the fellow who would give up his job and everything just to surf; a fellow who would become a bum and go to the beach and get in the way and give surfing a bad name?"

"No," Duke replied simply, "we kick them off. Any of the boys who come over we didn't like them and they come from the other side of town we'd just say, 'look, go back to ka-ka-ah-ko or any place we can figure, you see.' And these kids would stay away, until such time as they can behave themselves like a gentlemanand then we ask them in. Otherwise, they don't come out the beach, we just give them the thumb and that's pau [finished]."

Due to the outbreak of World War I, no Olympiad was held in 1916. Instead, Duke trained American Red Cross volunteers in water lifesaving techniques. With a group of American aquatic champions, he also did a nation-wide tour of sixteen cities in the United States and Canada to raise funds for the Red Cross. "But the point is," underscored Duke, "that the travel which my swimming afforded me also gave me the chance to demonstrate surfing wherever there was a satisfactorysurf."

Duke & Dad's Half Mile Ride of 1917

During this era, there were three particular surf sessions that were noted for their length and consequent fame. Greatest of them all was Tom Blake's 1936 ride from First Break, for an estimated distance of 4,500 feet. Then there was Duke's ride of 1932, averaging 1,000 feet. Lastly, but most memorable to Duke, was the ride he shared with Dad Center in 1917.

Duke and Dad were surfing Castles, in Waikiki, during a giant south swell in 1917. Many accounts of this ride - including Duke's toward the end of his life, confusing the 1917 ride with the other real long ride he had in 1932 - claim that during it, he was riding his 16 foot-long olo-design board. This just could not be. Duke did not experiment with olo designs until after Tom Blake replicated Chief Abner Paki's boards - the ones that had hung in the Bishop Museum for twenty years. Blake arrived on O`ahu in late 1924, left, and came back in 1926 when he refurbished Paki's boards and made replicas of both Paki's olo and alaia boards. In the process, he accidentally invented the hollow board, which he subsequently refined over the course of the next few years. Duke was inspired by Blake and got down on his own shaping at the very end of the 1920s. I have seen several sources mention Duke had his 16-footer by 1930.

Assuming the 1917 date is correct, then Duke probably rode his longest wave on his 10-foot , 3-inch thick alaia style redwood plank, not on the much longer olo shape he would later ride.

Some over-entusiastic estimates have the ride between a mile and 1 3/4 mile, starting far out from shore, on the edge of Steamer Lane. Duke, toward the end of his life, one time estimated it at 1 3/4 miles and then, another time, estimated it at 1 1/8 mile. Blake documented that Duke had told him, in the 1930s that it was a half mile.

Duke told a SURFER interviewer in the mid-1960s of what he remembered of the 1917 ride, but also confused it with his ride of 1932:

"I caught this big wave -- I would say between 25 and 30 feet -- on one of those days when the surf was so big. Well, a lot of the boys just grounded themselves and the others were still surfing. And I... went out to Castle. And I look at those doggone waves and I said, 'boy, these are really top waves.' And I said I'm going to take it whether I like it or not and I had to go," Duke laughed. "And I caught this wave and I came in and I started from Castle right out through Queenssurf. That's Queen's surf on the other side, close to the Canoe surf. And that's where I toppled; the point of my board hit the edge and knocked my balance andthat was the end of my run. Otherwise, if I hadn't done that, I would have gone right in to Happy Steiner's restaurant and The Tavern."

"During the Japanese earthquake," explained Tom Blake,"there was a long spell of big surf here of which the boys still talk. So it seems to be the jars, the shaking, the vibration from the inside of the earth that causes the big surfs.

"In a good, big surf the expert rider gets an average ride of three hundred yards, some four and even five hundred yards. In contrast, there are weeks at a time when the bay at Waikiki is so calm a ride of fifty yeards is a good one. Waves up to three feet high are running then.

"In 1917, during the Japanese earthquake surf," Tom Blake continued, "Duke and the well-known 'Dad' Center had two of the greatest rides in modern times. There are many stories about their ride. Duke pointed out to me one day, when we were surfing away outside, where the ride took place. Of that day in 1917, he says: 'It was about 8:30 in the morning, no trade wind yet, the ocean was like glass, except for the swells. They were running about thirty feet high. We were waiting for them off Castle Point [Ka-lehua-wehe], about five hundred yards outside the shallow coral and well to the west end of the break. We were so far out that we recognized the captain on the bridge of a passing steamer. A set of blue birds [big swells in blue water] loomed up. It looked as though they would break on us and we started paddling out, then stopped and decided to chance it. When the first one reached us it was just curling on top and very steep. Dad caught itand I took the next one. It took just one stroke to catch it; I had to slide hard to get out of the break. I went so fast the chop of the wave struck the bottom of my board like a patter of a machine gun. I figured the approximate speed. I was going about thirty miles an hour and when you are so close to the water you appreciate speed. That, along with the hazard of the wave breaking on me, made it quite interesting. I slid just a little too far west to make Cunha break. Dad Center did the same thing, this made the ride over a half mile long. That is not the limit, however, for I feel sure a ride twice that far is waiting for somebody."

In his own book, World of Surfing, written with Joe Brennan and published fifty years after the fact, Duke again recalled the details of this ride "as though it all happened yesterday, for, in retrospect, I have relived the ride many a time. I think my memory plays me no tricks on this one.

"Pride was in it with me those days, and I was still striving to build bigger and better boards, ride taller, faster waves, and develop more dexterity from day to day. Also, vanity probably had much to do with my trying to delight the crowds at Waikiki with spectacular rides on the long, glassy, sloping waves."

"But the day I caught 'The Big One' was a day when I was not thinking in terms of awing any tourists or kamaainas [old-timers] on Waikiki Beach. It was simply an early morning when mammoth ground swells were rolling in sporadically from the horizon, and I saw that no one was paddling out to try them. Frankly, they were the largest I'd ever seen. The yell of 'The surf is up!' was the understatement of the century.

"In fact, it was that rare morning when the word was out that the big 'Bluebirds' were rolling in; this is the name for gigantic waves that sweep in from the horizon on extra-ordinary occasions. Sometimes years elapse with no evidence of them. They are spawned far out at sea and are the result of cataclysms of nature -- either great atmospheric disturbances or subterranean agitation like underwater earthquakes and volcanic eruptions.

"True, as waves go, the experts will agree that bigness alone is not what supplies outstandingly good surfing. Sometimes giant waves make for bad surfing in spite of their size. And the reason often is that there is an onshore wind that pushes the top of the waves down and makes them break too fast with lots of white water (foam). It takes an offshore wind to make the waves stand up to their full height. This day we had stiff tradewinds blowing in from the high Koolau Range,and they were making those Bluebirds tower up like the Himalayas. Man, I was pulling my breath from way down at the sight of them.

"It put me in mind of the winter storm waves that roar in at Kaena Point on the North Shore. Big wave surfers, even then, were doing much speculating on whether those Kaena waves could be ridden with any degree of safety. The Bluebirds facing me were easily thirty-plus waves and they looked as though, withthe right equipment -- plus a lot of luck -- they just might be makeable."

"The danger lay in the proneout or wipeout. Studying the waves made me wonder if any man's body could withstand the unbelievable force of a thirty- to fifty-foot wall of water when it crashes. And, too, could even a top swimmer like myself manage to battle the currents and explosive water that would necessarilyaccompany the aftermath of such a wave?

"Well, the answer seemed to be simply -- don't get wiped out!

"From the shore you could see those high glassy ridges building up in the outer Diamond Head region. The Bluebirds were swarming across the bay in a solid line as far northwest as Honolulu Harbor. They were tall, steep and fast. The closer-in ones crumbled and showed their teeth with a fury that I had never seen before. I wondered if I could even push through the acres of white water to get to the outer area where the buildups were taking place.

"But, like the mountain climbers with Mount Everest, you try it 'Just because it's there.' Somedays a man does not take time to analyze what motivates him. All I knew was that I was suddenly trying to shove through that incoming sea -- and having the fight of my life."

Here, Duke confuses the 1917 ride with a later one he had in 1932: "I was using my papa nui [big board], the sixteen-foot, 114-pound semi-hollow board, and it was like trying to jam a log through the flood of a dam break."

"Again and again it was necessary to turn turtle," Duke continued with the longest ride story of 1917, "with the big board and hang on tightly underneath -- arms and legs wrapped around a thing that bucked like a bronco gone berserk. The shoreward-bound torrents of water ground overhead making all the racket of a string of freight cars roaring over a trestle. The prone paddling between combers was a demanding thing because the water was wild. It was a case of wrestling the board through blockbusting breakers, and it was a miracle that I ever gained the outlying waters.

"Bushed from the long fight to get seaward, I sat my board and watched the long humps of water peaking into ridges that marched like animated foothills. I let a slew of them lift and drop me with their silent, threatening glide. I could hardly believe that such perpendicular walls of water could be built up like that. The troughs between the swells had the depth of elevator shafts, and I wondered again what it would be like to be buried under tons of water when it curled anddetonated. There was something eerie about watching the shimmering backs of the ridges as they passed me and rolled on toward Waikiki."

"I let a lot of them careen by, wondering in my own heart if I was passing them up because of their unholy height, or whether I was really waiting for the big, right one. A man begins to doubt himself at a time like that. Then I was suddenly wheeling and turning to catch the towering blue ridge bearing toward me. I was prone and stroking hard at the water with my hands.

"Strangely, it was more as though the wave had selected me, rather than I had chosen it. It seemed like a very personal and special wave -- the kind I had seen in my mind's eye during a night of tangled dreaming. There was no backing out on this one; the two of us had something to settle between us. The rioting breakers between me and shore no longer bugged me. There was just this one ridge and myself -- no more. Could I master it? I doubted it, but I was willing to die in the attempt to harness it."

"Instinctively I got to my feet when the pitch, slant and speed seemed right. Left foot forward, knees slightly bent, I rode the board down the precipitous slope like a man tobogganing down a glacier. Sliding left along the watery monster's face, I didn't know I was at the beginning of a ride that would become a celebrated and memoried thing. All I knew was that I had come to grips with the tallest, bulkiest, fastest wave I had ever seen. I realized, too, more than ever, that to betrapped under its curling bulk would be the same as letting a factory cave in upon you.

"This lethal avalanche of water swept shoreward swiftly and spookily. The board began hissing from the traction as the wave leaned forward with greater and more incredible speed and power. I shifted my weight, cut left at more of an angle and shot into the big Castle Surf which was building and adding to the wave I was on. Spray was spuming up wildly from my rails, and I had never before seen it spout up like that. I rode it for city-long blocks, the wind almost sucking thebreath out of me. Diamond Head itself seemed to have come alive and was leaping in at me from the right."

"Then I saw slamming into Elk's Club Surf, still sliding left, and still fighting for balance, for position, for everything and anything that would keep me upright. The drumming of the water under the board had become a madman's tattoo. Elk's Surf rioted me along, high and steep, until I skidded and slanted through into Public Baths Surf. By then it amounted to three surfs combined into one; big, rumbling and exploding. I was not sure I could make it on this ever-steepening ridge. A curl broke to my right and almost engulfed me, so I swung even farther left, shuffled back a little on the board to keep from pearling (nose-diving).

"Left it was; left and more left, with the board veeing a jet of water on both sides and making a snarl that told of speed and stress and thrust. The wind was tugging my hair with frantic hands. Then suddenly it looked as if I might, with more luck, make it into the back of Queen's Surf! The build-up had developed into something approximating what I had heard of tidal waves, and I wondered if it would ever flatten out at all. White water was pounding to my right, so I angled farther from it to avoid its wiping me out and burying me in the sudsy depths."

"Borrowing on the Cunha Surf for all it was worth -- and it was worth several hundred yards -- I managed to manipulate the board into the now towering Queen's Surf. One mistake -- just one small one -- could well spill me into the maelstrom to my right. I teetered for some panic-ridden seconds, caught control again, and made it down on that last forward rush, sliding and bouncing through lunatic water. The breaker gave me all the tossing of a bucking bronco. Still luckily erect, I could see the people standing there on the beach, their hands shading their eyes against the sun, and watching me complete this crazy, unbelievable one-and-three-quarter-mile ride.

"I made it into the shallows in one last surging flood. A little dazedly I wound up in hip-deep water, where I stepped off and pushed my board shoreward through the bubbly surf. That improbable ride gave me the sense of being an unlickable guy for the moment. I heisted my board to my hip, locked both arms around it and lugged it up the beach.

"Without looking at the people clustered around, I walked on, hearing them murmur fine, exciting things which I wanted to remember in days to come. I told myself this was the ride to end all rides. I grinned my thanks to those who stepped close and slapped me on the shoulders, and I smiled to those who told me this was the greatest. I trudged on and on, knowing this would be a shining memory for me that I could take out in years to come, and relive it in all its full glory. Thishad been it.

"I never caught another wave anything like that one. And now with the birthdays piled up on my back, I know I never shall. But they cannot take that memory away from me. It is a golden one that I treasure, and I'm grateful that God gave it to me."

Tom Blake remembered that Duke had another great ride in 1932, "while we were surfing at Ka-lehue-wehe he picked up a big green comber, already curling at the top, about three hundred yards inside first break Ka-lehue-wehe and rode it through Public Baths surf, through Cunha and ended up inside Cunha oppositeQueen's, for a ride of about one thousand yards. This ride was made on his long hollow board."

"As a swimmer and surfrider," wrote Blake, "Duke, to me, is the greatest these Islands ever produced. Only after he has gone on will he be fully and generally appreciated. Duke's exceptionally fine physique is the exception rather than the rule among the Hawaiians as is the perfect body among any race today or in thepast and is the result of living under ideally healthy and happy carefree conditions in his boyhood years. He was on the beach all day long, swimming, surfridingor sleeping in the sun. He ate mostly poi and lau-lau (fish). I can say he lived a clean life in every way, resulting in the building of a body as fine as men of any country can attain. His exceptionally fine massive leg development does not come from riding in autos, but plowing through the sand bare-footed, in his youth. His well muscled shoulders and arms came from the surfboard work. His keen analytical turn of mind came from matching wits with big waves which were always scheming and eager to beat and smash him and his ancestors on the coral reefs."

Olympic Gold and Silver, 1920

Following World War I, "When the 1920 games at Antwerp, Belgium, rolled around," recalled sports columnist Red McQueen, "many thought that Duke at 30 was a bit too old to try out for the American team. But at the behest of Dad Center he whipped back into shape and defended his Olympic crown in a new world record time." Duke reestablished himself as "the world's fastest swimmer." He broke his previous world record in the 100 meter sprint with a time of 60.4 seconds.He also swam on the winning U.S. 800 relay team, along with fellow Hawaiian Pua Kealoha and haoles Norman Ross and Perry McGillivray.

Duke recalled 1922 as when he first started regularly surfing on the Mainland. "Well, I went up about 1922,' he told SURFER magazine, "and, of course at that time I was staying at Hollywood, and we managed to take a board and do some surfing down at Newport Beach in Balboa as they call it. There was just a few of us, a handful. We used to go down just about every weekend.

"One of the fellows that was with us... was Jerry Vultee... and he and I and the rest of us used to go down there almost every weekend at Newport and Balboa and I would teach him swimming... he wanted to teach me how to fly but we never got to flying... he and his wife took off one day on sort of a weekend and went down to Arizona someplace. And, on their return flight to Los Angeles, they hit a mountain and that was the end of them."

In 1924, Duke was dethroned in the swimming arena by one of his best friends. "It was not until the 1924 Paris Olympics," wrote biographer Timmons, "that he was defeated by Johnny Weismuller, who later went on to become Hollywood's first Tarzan. Duke would joke in later life that 'it took Tarzan to beat me.'"

Hawai`i still had cause to celebrate, however, because Duke, now age 34, brought home a silver medal in the 100 meter sprint and his younger brother Sam won the event's third place bronze.

Duke felt that surfing should be an Olympic sport. "Even as early as... [1918], I was already thinking of surfing in terms of how it could someday become one of the events in the Olympic Games. Why not? Skiing and tobogganing have taken their rightful place as official Games events. I still believe surfing will one day be recognized, voted in and accepted."

In the 1920s, it seemed that, finally, "The world was ready for Duke's arrival. But," queried Grady Timmons in his biography of Duke Kahanamoku, "was Duke ready for the world? After the rush of Olympic fame had subsided, he discovered that he could not go back to the carefree existence of a Waikiki beachboy.Success demanded something more. He was forced to lead two lives: one in and one out of the water."

This was the period when Duke did most all of his work with Hollywood. "On and off for four decades," wrote Timmons, "Duke played bit parts in twenty-eight films. Typically, he was cast in brown-skin roles -- an Indian chief, a Hindu thief, an Arab prince -- but rarely as a Hawaiian and rarely in his element." It was while he was on the Mainland that he made his most famous save.

Corona del Mar Save, June 14, 1925

The year after the Paris Olympiad, Duke and fellow surfers made the famous lifesaving effort at Corona del Mar, on June 14, 1925.

"It was in 1925 when I accidentally introduced another kind of surfing to California," Duke recalled, speaking of his introduction of the surfboard for lifesaving purposes. Long "recommended for the lifeguard service by Tom Blake," the surfboard's utility as a lifesaving device was dramatically demonstrated by Duke onJune 14, 1925, at Corona del Mar. This is how Duke tells the story of when he and a group of Hollywood actor and actress friends were picnicing on the beach and surfing:

"... some surfing pals and I were on the beach at Corona del Mar, approximately fifty miles south of Los Angeles. It was a day when anything could happen -- and did happen...

"Big green walls of water were sliding in from the horizon, building up to barnlike heights, then curling and crashing on the shore. Only a porpoise, a shark or a sea lion had any right to be out there. From shore we suddenly saw the charter fishing boat, the Thelma, wallowing in the water just seaward of where the breakers were falling with the CRUMP of tumbling buildings. The craft appeared to be trying to fight her way toward safe water, but it was obviously a losing battle. You could see her rails crowded with fishermen who, at the moment, certainly had other things in mind than fishing. Mine was the only board handy rightthen -- and I was hoping I wouldn't have to use it...

"In that instant my knees went to tallow, for a mountain of solid green water curled down upon the vessel. Spume geysered up in all directions, and everything was exploding water for longer than you would believe. Then, before the next mammoth breaker could blot out the view again, it was obvious that the Thelmahad capsized and thrown her passengers into the boiling sea. Neither I nor my pals were thinking heroics; we were simply running -- me with a board, and theothers to get their boards -- and hoping we could save lives.

"I hit the water hard and flat with all the forward thrust I could generate, for those bobbing heads in the water could not remain long above the surface of that churning surge. Fully clothed persons have little chance in a wild sea like that, and even the several who were clinging to the slick hull of the overturned boat could not last long under the pounding.

"It was some surf to try and push through! But I gave it all I had, paddling until my arms begged for mercy. I fought each towering breaker that threatened to heave me clear back onto the beach, and some of the combers almost creamed me for good. I hoped my pals were already running toward the surf with theirboards. Help would be at a premium.

"Don't ask me how I made it, for it was just one long nightmare of trying to shove through what looked like a low Niagra Falls. The prospects for picking up victims looked impossible. Arm-weary, I got into that area of screaming, gagging victims, and began grabbing at frantic hands, thrashing legs.

"I didn't know what was going on with my friends and their boards. All I was sure of was that I brought one victim in on my board, then two on another trip, possibly three on another -- then back to one. It was a delirious shuttle system working itself out. In a matter of a few minutes, all of us were making rescues. Some victims we could not save at all, for they went under before we could get to them.

"We lost count of the number of trips we made out to that tangle of drowning people. All we were sure of was that on each return trip we had a panicked passenger or two on our boards. Without the boards we would probably not have been able to rescue a single person..."

Newport's police chief called Duke's effort that day "the most superhuman surfboard rescue act the world has ever seen."

Of the 29 people on the Thelma, 17 died and 12 made it through. Of the 12, eight were rescued by the Duke using his surfboard. The whole incident was not quickly forgotten. Years later, in a front page story about the Duke, Los Angeles Times reporter Dial Torgenson wrote, "His role on the beach that day was more dramatic than the scores he played in four decades of intermittent bit-part acting in Hollywood films. For one thing, that day he was the star."

The Father of Modern Surfing

Legendary Hawaiian surfer Rabbit Kekai was born in 1920 and started surfing five years later. He remembers Duke and "the real old guys," as well as "the bigguys" at Publics. "Me and my younger brother learned to surf and angle cut the curl real early. When you get young training, like 5, 6, 7 years old, you get goodbasics. The way I learned was from watching the big guys. My uncle was a lifeguard and every day we'd go down to the beach, we'd see the big guys hangingaround. My cousin Louie Hema and I used to look up to David Hema (his father) and Albert Kauwe (who was custodian at Public Beach Park). Another guy inour family we also used to look up to was Chuck-A-Long, he was one of the greatest, and a guy named Gabe Tong who was a fire chief, and another guy theycalled 'Hawaiian,' his name was Carlos Naluai. They used to be the big guys down there, riding those 11' to 12' redwood planks out at Publics."

Duke's 16-foot olo design

At one point, Duke had the biggest board of anyone. It was a 16-footer, made of koa wood, weighing 114 pounds, and designed after the ancient Hawaiian olo board. To Duke, big boards were for big waves. "With his rare expertise and outstanding strength," Brennan wrote, "Duke handled it well in booming surfs. Heused to defend his giant board and kid fellow surfers with, 'Don't sweat the small stuff. Reason? Because it's small stuff.'"

Duke's Papa Nui had been inspired by Tom Blake's refurbishment of 1800s Hawaiian Chief Abner Paki's boards and his resulting development of the hollowboard. Duke made his 16-footer around 1930.

Asked in an interview about the longer boards of the time, Rabbit answered, "That was only Duke and the real old guys who rode those sixteen footers. Of course, there was Blake and that other guy, Sam Reid, who about that time introduced the hollow, cigar-shaped box boards."

Rabbit Kekai