the 39th Scout Dog Platoon | home

PLATOON ROSTER | DOGS | ARTICLES | BUDDA'S STORY | DOG ART | FAVORITE LINKS | REUNIONS | DOG TEAM OF THE MONTH | PHOTOS | UNIDENTIFIED | NOTICES | GUEST BOOK

ARTICLES

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Our weekly papers

East Penn Press, Salisbury Press, Parkland Press, Northwestern Press, Whitehall-Coplay Press, Northampton Press, Pocono Post December 13, 2000

War dogs

Vietnam veteran remembers

his canine companion

By Mary Ann Endy

Press writer

Writer's note: This story is dedicated to the Vietnam veteran dog handlers and their dogs who saved thousands of American lives. Its intent is to give long overdue recognition to all of our four-legged heroes, whether in times of war or peace. Members of the K-9 Corps are American patriots, too. World War II baby boomers grew up with Rin Tin Tin and Lassie as their animal heroes. By the time they were in their teens, another war was escalating, this time in Vietnam.

The young men graduating from high school either enlisted or were recruited through the draft lottery to serve their country. Some would march off to war and volunteer to become dog handlers. Their dogs became real American heroes who saved thousands of lives, often sacrificing their own in the process. A K-9 recruitment drive, for service in Vietnam, was launched by the military. Patriotic kennel owners and private donors responded to the war effort by sending their German shepherds and Labrador retrievers. For them, it was like sending their children off to war.

In the 1990s, like so many of their comrades, the dog handlers would begin to reflect on their Vietnam experiences. Hidden deep in their souls they carried a heart-wrenching story of leaving behind these four-legged heroes who prevented more than an estimated 10,000 casualties in Vietnam. At the end of the Vietnam War, the American dogs, which were declared by the military as "equipment," were left behind. Records show that only 204 came home. Their fate for heroism was either a transfer to the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) or to be euthanized. Handlers fear the worse scenario was that some of their dogs became a delicacy for the Vietnamese. The war dogs became another tragedy of the Vietnam War. With the fall of South Vietnam in 1975, the dogs were abandoned, along with helicopters, tanks and the other articles of war. The government's reason for leaving the dogs behind was that they had contracted diseases or that they might attack civilians. Yet, during World War II, thousands of dogs were demilitarized and returned, either to their original owners or to the handlers who had fought alongside them. Dog handlers boarded planes home from Vietnam with mixed emotions, having difficulty accepting the separation from their dogs but happy to be returning home to families and friends.

During their 12-or-more-month tour of duty, handlers bonded emotionally with their dogs as if they were their own, since their own lives depended on them. Scout dogs were more than just dogs; they were the handlers' best friends and the only reason that many survived. Soldiers died trying to save their dogs' lives, and many canines took the brunt of booby trap explosions, saving the lives of their handlers. The dogs warned troops about ambushes and saved lives by dragging wounded soldiers to safety, without consideration for their own wounds. The military did not keep accurate records. However, it is estimated that approximately 10,000 handlers and 4,000 dogs served in Vietnam. Estimates also show that 263 handlers and 500 dogs made the ultimate sacrifice in Vietnam.

The teams were so effective in Vietnam that the Viet Cong posted bounties on the handlers and their dogs. Handlers considered the bounty a compliment to their effectiveness in the bush. The VC regarded the American dogs as a major problem. They could run, but with a well-trained dog scouting them, there was no place to hide. The German shepherd intimidated the Vietnamese. Many were Buddhist and feared that they would be reincarnated as a dog. Enemy soldiers were rewarded if they brought in a handler patch or the tattooed ear of a scout dog. The VC tried to infiltrate by using different sprays and pepper to disguise their human scent. The enemy tried to reduce the number of dogs by targeting the dog kennels on the bases with mortar attacks. The VC fought a guerrilla action, requiring an appropriate response with effective countermeasures and, because of this, the army decided to reactivate its scout dog program in 1965.

Dogs were used because of their powerful sense of smell, acute hearing and superior night vision. They may also possess some type of extrasensory perception.

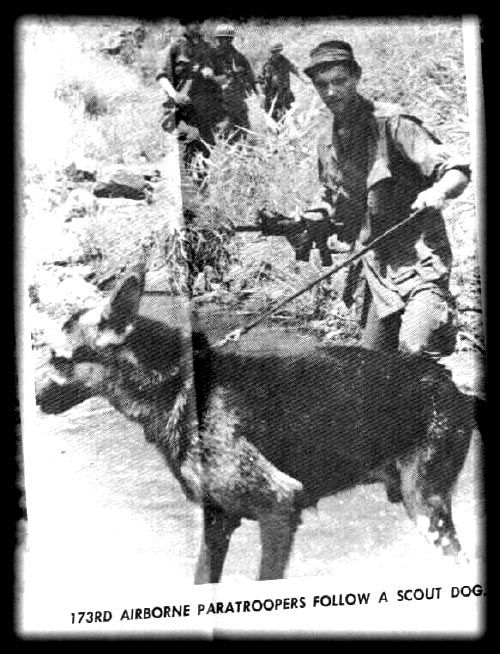

German shepherds were best suited for sentry and scout duty because of their intelligence and adaptability. Labrador retrievers made great tracker dogs because of their strong sense of smell and mild disposition. The scout dog team walked point in front of the patrols and searched out enemy traps and ambushes. Walking the point meant they were always out in front of a patrol. It was a very dangerous job in Vietnam. The dogs would assist village search operations. They assisted infantry units for supply and personnel interdiction. Their job was to give a silent early warning (that meant no barking) of any enemy outside the main body. Scout dogs were in demand by platoons because of their effectiveness. "Sentry dogs" defended the perimeter of the military bases. They provided a psychological boost for the handler on nightly patrols and a deterrent to enemy infiltrators. Sentry dogs proved themselves repeatedly by alerting of infiltrators on the ground. These dogs maintained perimeter watches at Bien Hoa, Binh Thuy, Cam Ranh Bay, Da Nang, Nha Trang, Tluy Hoa, Phu Cat, Phan Rang, Tan Son Nhut and Pleiku. "Tracker dogs" pursued fleeing ambushers and located downed pilots. The Labrador retrievers were docile, could tolerate heat reasonably well and favored the dead scent of ground sniffing. Their alerts were wagging the tail, raising the head, twitching an ear or simply stopping. These dogs were trained to follow only one scent on the ground. This scent needs to be given to the dog, usually by having him sniff an enemy footprint or a blood trail. The scent is as unique as a person's fingerprint. The main mission for any tracker team is to re-establish contact with retreating or evading enemy troops and to investigate areas of suspected enemy activity. Tracking was performed during daylight hours. "Mine dogs" worked primarily along roads and railroad tracks, looking for mines, booby traps and trip wires. Tunnel dogs alerted by sitting about two feet from the trip wire or tunnel entrance. Commanded by hand and arm signals, since the VC could be hidden inside, mine and tunnel dogs worked off-leash. "Water dogs" smelled enemy divers hidden beneath the surface of rivers. They were used by the Navy to detect VC swimmers planting mines in the water. They were able to pick up the scent if the enemy used a reed to breathe through. The recruited dogs were first evaluated for good health. They could not weigh less than 60 pounds and had to be between one and three years of age. The biggest concern regarding the German shepherds was hip dysplasia, which can develop into arthritis, ending the dog's military usefulness.

The selected dogs then began extensive training to change them from ordinary house pets into war dogs. They were trained in obedience, vigorous exercise through obstacle courses, advanced lessons to detect human scent in tunnels, tracks and land mines, and the sound of the wind on a trip wire. All of these lessons were important for the survival of both the dog and the handler in the jungles of Vietnam. Soldiers from all the branches of the military volunteered to become handlers. To qualify, they needed to have a friendly attitude toward dogs, patience and perseverance, physical endurance and the ability to exercise common sense. Brian Taras of Lehigh Township served in the United States Army in the 39th Infantry Scout Dog Platoon attached to the 173rd Airborne Division, II Corps, LZ English, South Vietnam, in the central highlands and mountains, from June 1969 to June 1970. After being drafted and undergoing advanced infantry training, Taras was sent to Fort Benning, Ga. A walk past the dog kennels on the base changed his life forever.

"I always liked dogs," Taras said. The next day he made an inquiry on becoming a dog handler. "That was the best thing I ever did," he said. Taras trained at Fort Benning for 12 weeks before being deployed to Vietnam.

The handlers and dogs trained as a team at Fort Benning and Lackland Air Force Base, Texas. Handlers learned how to take care of the dogs (feeding, grooming and first aid), interpret the dog's body language (their alert) and command them by the use of the hand-sign and voice. The dog's alert could mean the difference between life and death. Each handler could interpret his dog's alert-on some, their ears would straighten up. Field instruction was to teach the handler and dog to work as a team in alerting others of enemy presence. The dog was taught to give only a silent warning, since barking would alert the enemy. The team developed a sense of trust between them. Another part of the training included a simulated VC village and simulated combat conditions. The war dogs were trained to recognize booby traps, Punjii pits (sharpened stakes of bamboo that caused serious injuries-even amputations), mines, tunnels and weapon caches. Bien Hoa Air Base (outside of Saigon) in South Vietnam was the next stop for both handler and dog. In most cases, the two did not come there together, unless it was a unit move. There were already dogs in Vietnam waiting for the new handlers.

Taras was matched with a beautiful young female German shepherd named Gretel. He quickly flips through his scrapbook of war memorabilia to show off his pride and joy. One senses that this bond was deep. He cannot say enough about her. "Beautiful dog-very smart," Taras proudly recalls. He quickly adds, "The females were smarter than the males." Gretel and he were a scout team for his entire tour of duty.

After their arrival, they underwent in-country training at the air base for two weeks. Personalities of the handlers were matched with the dogs. Veteran dogs (their previous handler had gone home) helped teach their new handlers. Together, they were a team that cared, shared and looked out for each other, forming special bonds. "With Gretel, you had an early warning detection system," Taras says. "Her alert sign was the movement of her head-the upshot of her ears." He added that when the handler was walking one way and suddenly the dog would go the other way, something was up.

After in-country training, the teams were off to their combat destination where they would again train to familiarize themselves with the terrain in which they worked. Taras says that new handlers with their dogs on a first mission went out with an experienced handler. After that, the handler and dog were their own. "It was very scary out there," Taras remarked. They shared the same bedroll out on the field. In Vietnam, the dogs were the best psychologists the army had. The handlers and dogs shared many conversations, with the dogs making good listeners. Handlers even read the dogs their letters. Stories are told that they shared "Dear John" letters with their dogs, who afterwards brought them some relief by chewing up the letter. Together each day, they faced other problems besides combat-snakes, heat stroke, quick sand and chemicals. Taras says these dogs worked for praise and affection-there were no biscuits there. He talks about how the guys in the platoon all loved Gretel. They would just come over to hug her, he explained.

Dogs received medical care, just like the soldiers. Enlisted animal specialists, which were referred to as "vet techs," were assigned to each scout platoon. The vet techs trained at Walter Reed Army Institute of Research in Washington, D.C. They provided preventive medicine, first aid and routine treatments. Graduate veterinarians were at larger bases, treating dogs for diseases and injuries.

"A platoon may have had 27 dogs in it," Taras says. What was nice about being a handler, he explained, was meeting new people. Handlers were highly respected because of the lives the dogs saved. "We were a point dog team," Taras said. The teams rotated and were out seven days and in 10 days. There was a high casualty rate amongst the handlers and dogs because of being out there in front of the platoon. There were many booby traps and Punjii pits, Taras recalled. When out on a mission, the handler carried the dog's food and water supply in addition to his own belongings. According to Taras, a dog ate about five pounds of dog food per day. "I saw people blown up for not following the dogs," Taras explained. He stressed that it was very important to watch and follow their alert.

He praises Gretel's contributions to the war. "Gretel found a North Vietnamese hospital," said Taras, explaining it was hidden on the top of a mountain in the ground like a tunnel. "Gretel discovered a cache of antipersonnel mines (land mines)," Taras continued. "They would have been used to kill many of our soldiers. And she found crates of Browning and Thompson submachine guns," Taras added. The submachine guns were old, like the kind that the gangsters used in days of Al Capone, he explained.

Taras recalls one of Gretel's biggest discoveries. He explained that they were patrolling the perimeter of a base that had just been attacked and he and Gretel had gone on patrol outside the perimeter. "The dog found a notebook containing names of people in South Vietnam who the enemy could go to for help," he said. The people were South Vietnamese by day and Viet Cong by night. The notebook gave the military insight into who could not be trusted.Gretel made an unusual discovery when she alerted on three fresh graves. Two graves contained the bodies of South Vietnamese soldiers who had been shot through the head. The third grave contained the body of a Russian advisor who was dressed in civilian clothes. Taras explained they did go into Cambodia. There, they found tons of ammunition, helping to save many American lives. Shortly after that find, he received a letter from his mother, Iola. The letter contained a newspaper clipping telling how Americans were protesting the war and the United States involvement in Cambodia. He said the information was difficult to digest because of the need to save the lives of many American soldiers.

He summed up his Vietnam experience. "You tried to come back alive," Taras explained. "I carried a submachine gun that had to be fired with one hand; in the other hand was the dog on the leash." Taras was awarded the Purple Heart twice. "On my birthday, Aug. 20, 1969, I got shot in the neck and then on April 11, 1970, I was wounded in the leg," he explained. Taras also received the Bronze Star and the Army Commendation medal.

Recognition of Gretel and the other war dogs is more important to Taras than recognition of his own service to our country. Gretel is not a forgotten hero in the eyes of her handler.

In June 1967, a disease appeared in many dogs that soon became an epidemic. Dogs developed a fever for several days or weeks and then would recover. The dog appeared healthy for the next few months and then would suddenly start bleeding from the nose.

The dog lost its appetite and weight. It would developed sores and have weakness in its hind legs. Death occurred within a few days. Within several months, 89 dogs died in 15 different platoons. The disease was first called idiopathic hemorrhagic syndrome (HIS), but was later termed tropical canine pancytopenia (TCP). The disease was traced to ticks that were imported with tracker dogs obtained from the British in Malaysia. The disease spread through veterinary detachments. A few years later, it was found that TCP had been prevalent in the United States for years.

Gretel died from TCP in Vietnam shortly after Taras returned home. "I would have stayed with Gretel and not come home if there would have been something I could have done to prevent her death," Taras explained. "She saved many lives and there are a lot of veterans here in the states who would have been dead if it was not for her courage and loyalty."

Taras honored her by purchasing a brick with her name on it. The brick is located on the walkway at the Lehigh Northampton Vietnam Veterans Memorial, located at VFW Post 9264 in Macungie.

Handlers who served in Vietnam formed a nonprofit organization in 1993 known as the Vietnam Dog Handlers Association. The VDHA is trying to arrange the issuance of a commemorative stamp honoring the war dogs. The stamp is under consideration by the Citizens' Stamp Advisory Committee.

For additional information on the VDHA, visit the Web site at http://www.vdhaonline.org. The Web site also contains links to other information on the handlers and their dogs.

This year, two war dog memorials were erected and dedicated: one on Feb. 21 at March Field Air Museum in Riverside, Calif., and the other on Oct. 8 at Fort Benning, Ga.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------