Political Fiction is nothing revolutionary. Indeed, there are even historic precedents of it. As always, we look first to the Greeks. Plato's Republic, although a speculative political philosophic work, becomes a springboard for political fantasy's "what-if" format. Here Plato, speaking through or for Socrates, sets up a communistic society where children are cared for in common, men are assigned positions according to their nature, "Guardians" (the cream of society) of both sexes care for the daily needs of the society, and the whole is ruled by the famous "philosopher king."

Until philosophers are kings, or the kings and princes of this world have the spirit and power of philosophy, and political greatness and wisdom meet in one...cities will never have rest from their evils-no, nor the human race, as I believe-and then only will this our State have a possibility of life and behold the light of day.2

The main difference between Political Fiction, or Political Fantasy, and this Speculative Political Philosophy, is that while a completely different society is created, qualifying it for fantastic fiction, the work does not employ the standards of character or plot necessary for prose fiction.  Given Plato's ostensible dislike for poetry or any fabrication, one is surprised that he even flirts with the creation of a different society.

Given Plato's ostensible dislike for poetry or any fabrication, one is surprised that he even flirts with the creation of a different society.

Conversely, Homer's Iliad is an excellent example of Political Literature whose scope to the modern reader may at first be considered fantastic, comprising as it does the workings of gods, magic, heroes and fate. But the modern reader must remember that this classic work was written in the completely realistic vein of its time and therefore is an example of Political Fiction, although its style and indeed all mythology contributed to the development of modern fantasy.

The Iliad is, in one sense, the story of what happens when political leaders put their own interests before the interests of their people. Beginning with the power struggle between Achilles and Agamemnon over Briseis and then blossoming out to encompass the larger political struggle between the Achaeans and the Trojans over Helen, Homer dissects the politics that begin and sustain a war. "Courage is the secret of power," Diomedes rebukes Agamemnon in the ninth chapter, followed soon after by Nestor's advice that "man is indeed an enemy of his country, clan and hearth who enjoys the bitter taste of civil war.3" Likewise, Priam shows his own kingly weakness when he says to Helen, "I bear you no ill will at all: I blame the gods.4"

Homer does not stop at the selfish politics of the Greeks and the Trojans, but probes even the hierarchy of the gods, since the divine has a place in every political schema. Zeus is the king of the gods, manipulating his court and their involvement in the war. He proves the classical ideal of an absolute monarchy-as well as its practical impossibility-when he rebukes his nagging (and often successfully political) wife, Hera, by saying, "When I choose to take a step without referring to the gods, you are not to cross-examine me about it.5" However, even Zeus is subject to Fate: "Father Zeus hung his golden balances and set in one the lot of Hector's death and in the other that of Achilles. Hector's lot sank down. It was appointed that he should die.6"

Following fast on the heels of the Iliad is Virgil's Aeneid. This classic Roman epic's whole scope is consumed by Æneas' destiny to be the founder of Rome, and from there of the Roman Empire. Again Fate takes a prominent place in the political hierarchy of the ancient world, as the opening stanza proves.

Arms and the man I sing, who, forced by Fate,

And haughty Juno's unrelenting hate,

Expelled and exiled, left the Trojan shore.

Long labors, both by sea and land, he bore,

And in the doubtful war, before he won

The Latian realm, and built the destine town;

His banished gods restored to rites divine:

And settled sure succession in his line,

From whence the race of Alban fathers come,

And the long glories of majestic Rome.7

His first encounter with a royal monarch after the fall of Ilium is with Dido, Queen of Carthage, who again proves the destructive nature of a selfish monarch.  As her sister laments over Dido's dead body, "At once thou hast destroyed thyself and me,/Thy town, thy senate, and thy colony!8" Although the gods and destiny compel Æneas to found what was to be the greatest empire of the ancient world, still Æneas must overcome on his own those tender-hearted sentiments so atypical of the ideal Roman citizen. Therefore Virgil ends the epic with the hero's deliberate murder of his last obstacle to Rome. "He rolled his eyes, and every moment felt/His manly soul with more compassion melt;/When, casting down a casual glance, he spied/The golden belt that glittered on his side..../Then, roused anew to wrath..../He raised his arm aloft, and.../Deep in [Turnus'] bosom drove the shining sword.9"

As her sister laments over Dido's dead body, "At once thou hast destroyed thyself and me,/Thy town, thy senate, and thy colony!8" Although the gods and destiny compel Æneas to found what was to be the greatest empire of the ancient world, still Æneas must overcome on his own those tender-hearted sentiments so atypical of the ideal Roman citizen. Therefore Virgil ends the epic with the hero's deliberate murder of his last obstacle to Rome. "He rolled his eyes, and every moment felt/His manly soul with more compassion melt;/When, casting down a casual glance, he spied/The golden belt that glittered on his side..../Then, roused anew to wrath..../He raised his arm aloft, and.../Deep in [Turnus'] bosom drove the shining sword.9"

Shakespeare's histories hone the art of political literature, especially in the creative non-fiction play Richard III. While the great epics dealt with several themes, including the political, the master bard's play centers on one man's attempt to win and hold the throne of England by any means necessary. Several deaths are brought about at the usurper's hands, as well as a seduction, and finally a war that disposes of the tyrant. Shakespeare focuses on the question of how such a man could come into power.

England hath long been mad, and scarred herself-

The brother blindly shed the brother's blood,

The father rashly slaughtered his own son,

The son, compelled, been butcher to the sire....

Abate the edge of traitors, gracious Lord,

That would reduce these bloody days again

And make poor England weep in streams of blood!10

Shakespeare's Julius Caesar also questions how easily a society can be reshaped by a political creature. Mark Antony's famous speech in Act III is a classic example of soapboxing. "The noble Brutus/Hath told you Caesar was ambitious./If it were so, it was a grievous fault,/And grievously hath Caesar answered it..../[Caesar] was my friend, faithful and just to me./But Brutus says he was ambitious,/And Brutus is an honorable man.11" By the repetition of this last phrase, Mark Antony is able to turn the tide against Brutus by the use of grim irony. Shakespeare has successfully dissected a political move, laying it bare for those who would see the same manipulation in the politics of his own day.

But Shakespeare did not stop there. He also introduced some of the first "realistic" and supposedly "non-fiction" plays that spilled over into the fantastic.  Hamlet, a laboratory for the destructive nature of revenge in a political situation, includes a ghost whose impetus begins and continues the whole of the action with the words, "Revenge his foul and most unnatural murder.12" Likewise, Macbeth includes the fantastic elements of not only a ghost, but also witches who spur on the action. After first meeting the weird sisters in Act I, Macbeth says, "My thought, whose murder yet is but fantastical,/Shakes so my single state of man that function/Is smothered in surmise, and nothing is/But what is not.13"

Hamlet, a laboratory for the destructive nature of revenge in a political situation, includes a ghost whose impetus begins and continues the whole of the action with the words, "Revenge his foul and most unnatural murder.12" Likewise, Macbeth includes the fantastic elements of not only a ghost, but also witches who spur on the action. After first meeting the weird sisters in Act I, Macbeth says, "My thought, whose murder yet is but fantastical,/Shakes so my single state of man that function/Is smothered in surmise, and nothing is/But what is not.13"

The element of the fantastic is continued and expanded on in Saint Thomas More's Utopia. Indeed, except that the country of Utopia could be found somewhere in this world, the classic satire could almost pass for a perfect example of Political Fantasy. In the work, More takes the political and social absurdities and brings them to their logical conclusion in this fictional country in order to make the reader acutely aware of them. In the first book, he condemns certain English practices through the mouth of the sailor Raphael Hythloday, such as the famous line, "In this point, I pray you, what other thing do you, than make thieves and then punish them?14" Book two then describes Utopia and its outrageous laws, which all too closely resemble our modern state. The inhabitants preach a religion of "tolerance," such as Voltaire described in the Enlightenment, decreeing that "no man shall be blamed for reasoning in the maintenance of his own religion.15" The result, of course, is Protestantism, or "liberal" Christian theology. Men and women are equalized, working together in the fields and towns, and even going into battle together. All this is decreed by the councils and the king.

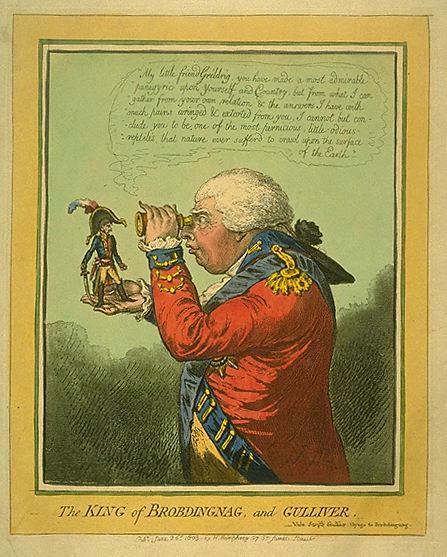

More's Utopia still lacks the element of driving plot, rather than plot narration, that is a key element in fiction. The work is somewhere between Plato's Republic and the modern examples of Political Fantastic Fiction. As if to remedy this, and to carry on and expand More's remarkable book, Jonathan Swift offers the world Gulliver's Travels. Again written with a keen satiric edge, this book leans more towards the novel form than the treatise. Besides the use of plot and main character, the work explores four different sociopolitical fabricated nations. Because of the time period Swift wrote in, the option of completely separating these created places from this world altogether was not explored, much less known, but the ties to this world are tenuous at best, only found in Gulliver himself.

The three books describe several different nations, each radically different from the others. The first is that of the Lilliputians, who are ruled by an Emperor, extraordinarily small in stature but self-important enough to make up for this apparent deficiency. The second book concerns itself with the nation of Brobdingnag, the home of the peaceful monarchial giants, whose king comments on our society that "I cannot but conclude the bulk of your natives to be the most pernicious race of little odious vermin that nature ever suffered to crawl upon the surface of the earth.16"

Laputa, the third country, is entirely peopled and governed by "enlightened" intellectuals whose bodies reveal their overweening "rationale."

Their heads were all reclined either to the right or the left; one of their eyes turned inward, and the other directly up to the zenith.... It seems the minds of these people are so taken up with intense speculations that they can neither speak nor attend to the discourses without being roused by some external taction upon the organs of speech and hearing.17

Combined with Laputa, the floating island, is Lagado, the metropolis beneath it, which is run ragged attempting to keep up with the times. As one noble comments, "he must throw down his houses in town and country, to rebuild them after the present mode...and give the same directions to all his tenants, unless he would submit to incur the censure of pride, singularity, affectation, ignorance, caprice, and perhaps increase his Majesty's displeasure.18"  Glubbdubdrib, the land of magicians and especially necromancers, explores this world's history, concluding with Gulliver's saying that he was "chiefly disgusted with modern history.... I found how the world had been misled by writers....how many villains had been exalted to high places.19" Luggnagg's king is more totalitarian, as well as sadistic-a feature demonstrated by the poisonous dust that persons in disfavor are required to lick.

Glubbdubdrib, the land of magicians and especially necromancers, explores this world's history, concluding with Gulliver's saying that he was "chiefly disgusted with modern history.... I found how the world had been misled by writers....how many villains had been exalted to high places.19" Luggnagg's king is more totalitarian, as well as sadistic-a feature demonstrated by the poisonous dust that persons in disfavor are required to lick.

The final nation is the Houyhnhnm's Country-a nation completely governed, not by a philosopher king, an aristocracy, or any sort of human politic-but by horses in a type of community. In this society, Swift studies the use of lying, or as the Houyhnhnms say, "the thing which was not. (For they have no word in their language to express lying or falsehood.)20" In this particular country, Swift also introduces "Yahoos," who are Darwinian devolved humans-the only ones capable of deceit. The meaning is clear: only true brutes (humans) can deceive, and use deceit in governing. As Swift says, "Power, government, war, law, punishment, and a thousand other thing had no terms wherein his language could express them, which made it difficult to give my master any conception of what I meant.21" From this country only, Gulliver is forced to return home (rather than fleeing back to England). As he explains, "When I thought of...[the] human race in general, I considered them as they really were: Yahoos in shape and disposition, perhaps a little more civilized...but making no other use of reason than to improve and multiply their vices.22"

Even Swift's excellent book, though, has not completed the change from Political Fiction to Political Fantasy, and indeed still has remnants of a cleverly hidden political philosophic work. Not until this century has true Fantasy been possible, and in that genre, only a few have dared to touch upon the possibilities inherent in the subgenre of Political Fantasy. Indeed, if the Supergenre of Fantastic Fiction has been utilized for the study of politics in fiction form, Science Fiction has held sway almost exclusively.

Let us briefly return to the definitions and prerequisites for Political Fiction, both Fantastic and Realistic. Fiction necessitates a definite plot, discovered by characters, exemplifying a thought (or idea). This is different from political treatises whose main thrust is the thought-plot and characters become optional secondary devices to make the work palatable, such as Socrates' dialogues, or More's Utopia. Both Fantastic and Realistic Fiction, then, use plot and character as the necessary primary devices in order to exemplify the thought. For art and media of any kind is a sort of everyman's philosophy.

This fervor of poesy is sublime in its effects: it impels the soul to a longing for utterance; it brings forth strange and unheard-of creations of the mind; it arranges these meditations in a fixed order, adorns the whole composition with interweaving of words and thoughts; and thus it veils truth in a fair and fitting garment of fiction.23

But Political Fiction is that literary dissection of the moving forces behind a society. The author focuses on one political system and studies it through the means of his craft. Political Science Fiction, then, focuses on a speculative political system in the future of our world, or somewhere in our universe. The result is literary extrapolation of a certain politic evident in today's society.

Orwell's 1984 is perhaps the preeminent example of Political Science Fiction. Written around the time of the Second World War, the book examines the methods used by totalitarianism: the manipulation of history, words, and ideas upon the common man. The story follows an everyman, such as Chesterton advises: Winston Smith, who struggles against the mindnumbing world of "Big Brother," and fails.  The slogans "War is Peace. Freedom is Slavery. Ignorance is Strength24" immediately demonstrate the twists that the political regime has set up against common sense. "Newspeak," a regulation of words, is obviously a political move to control the people, as much as the "Two Minutes Hate" and the "Junior Anti-Sex League."

The slogans "War is Peace. Freedom is Slavery. Ignorance is Strength24" immediately demonstrate the twists that the political regime has set up against common sense. "Newspeak," a regulation of words, is obviously a political move to control the people, as much as the "Two Minutes Hate" and the "Junior Anti-Sex League."

"The A vocabulary consisted of the words needed for the business of everyday life.... It was composed almost entirely of words that we already possess...but in comparison with the present-day English vocabulary, their number was extremely small, while their meanings were far more rigidly defined. All ambiguities and shades of meaning had been purged out of them.... The B vocabulary consisted of words which had been deliberately constructed for political purposes: words, that is to say, which not only had in every case a political implication, but were intended to impose a desirable mental attitude upon the person using them.... The C vocabulary was supplementary to the others and consisted entirely of scientific and technical terms."25

Orwell was not unaware of the import or subject of his work in this particular subgenre. In his essay "Why I Write," he says:

What I have most wanted to do throughout the past ten years is to make political writing into an art. My starting point is always a feeling of partisanship, a sense of injustice.... I write it because there is some lie that I want to expose, some fact to which I want to draw attention, and my initial concern is to get a hearing.26

And a hearing Orwell received. 1984 is read in almost every school, one of the few fantastic fiction books to "get a hearing," to be considered worthy of notice by those smaller political forces that determine the academic curriculum. Another author concerned with the political power of literature is Ray Bradbury, whose Fahrenheit 451 is as highly revered in the educational system as 1984. In Bradbury's vision of the future, the "firemen"-of whom the main character, Guy Montag, is one-burn books, rather than putting out fires. Like 1984, Bradbury is concerned with the political move to dehumanize the people, in this case through massive home entertainment cinemas: wall-TV. As Clarisse McClellan, the voice of normality, says, "People don't talk about anything.27" Later, as Montag discovers his burgeoning contempt for a world so full of nothingness, he wonders, "How do you get so empty?...Who takes it out of you?28" Beatty, the Firechief, answers,

It didn't come from the Government down. There was no dictum, no declaration, no censorship to start with, no! Technology, mass exploitation, and minority pressure carried the trick.... We must all be alike. Not everyone born free and equal, as the Constitution says, but everyone made equal.... A book is a loaded gun in the house next door. Burn it.... Who knows who might be the target of the well-read man?29

Unlike Orwell's dismal view of such a restrictive society, however, Bradbury offers hope at the end of the book. Montag, fleeing from his home, comes upon a group of renegades who store books in their minds, word for word, until they become "nothing more than dust-jackets for books.30" And ultimately, the world Bradbury envisions-a world that burned books and the men who wrote those books-burns itself in the light of a single bomb, leaving behind only those who kept to the old ways. As the book asks,

Is the purpose of a government to make people happy or to make them bigger, deeper individuals even if this does not lead them to happiness?... In any organization, how much difference do you allow under the name of democracy or tolerance before you have to destroy the difference in order to preserve your organization?31

Huxley's Brave New World is the third of the major Political Science Fiction works, although there are certainly many others within the Genre. Like his contemporaries, Huxley concerns himself with what he and the others see as the main threat inherent in the present politics of the world: the dehumanization factor. In Brave New World, Huxley introduces the theme as he sees it: either national or supernational totalitarianism, "developing, under the need for efficiency and stability, into the welfare-tyranny of Utopia.32" Like Orwell and Bradbury, Huxley wrote his masterpiece in the political chaos during and after the Second World War, developing a future similar to the visions of 1984 and Fahrenheit 451.

In this society, all children are marked from birth according to their grade value-indeed, they are bred as a certain type of human from the very outset, rather like a scientifically advanced Republic. " 'We also predestine and condition. We decant our babies as socialized human beings, as Alphas or Epsilons, as future sewage workers or future....' He was going to say 'future World controllers.'33" Proletariats and politicians are formed by those very "World controllers. Huxley from the beginning shows us the dangerous political possibilities man could have over his fellow man if allowed to dabble into that miracle of generation.

The plot is complicated when the world, stupefied by its soma drugs, happens upon a Savage-one who has lived in what we would consider a normal fashion, "at one with the earth." He is immediately set upon, studied, and eventually brought out of all society and into a final confrontation with the Controller himself. In that interview, they discuss several issues pertinent to the question of who holds the reins of politics: man, society, or God. As the Controller says of his society, "People believe in God because they've been conditioned to believe in God.... But [God's] code of law is dictated, in the last resort, by the people who organize society; Providence takes its cue from men.34"

With this simple interchange, Huxley touches on the quivering heartbeat of the true struggle of politics through the ages: the struggle between God and man. For if man were to wrest from God all that is His by rights, he must, in order to keep that control, somehow rid the society of God, so that the common man will believe that the temporal and human politic is the highest authority.

2 Plato. "The Republic." Plato. Trans. J. Harward. Chicago: Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc., (c) 1952. p. 369.

3 Homer. Iliad. Trans. E. V. Rieu. Baltimore: Penguin Books, (c) 1966. p. 162.

4 Ibid. p. 68.

5 Ibid. p. 37.

6 Hamilton, Edith. Mythology: Timeless Tales of Gods and Heroes. New York: Mentor Books, (c) 1942. p. 190.

7 Virgil. Aeneid. Trans. John Dryden. New York: Hurst & Company, (c) unknown. p. 11

8 Ibid. p. 117.

9 Ibid. p. 364.

10 Shakespeare, William. "Richard III." Shakespeare: The Complete Works. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, Inc., (c) 1968. p. 269.

11 Shakespeare, William. "Julius Caesar." Shakespeare: The Complete Works. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, Inc., (c) 1968. p. 832.

12 Shakespeare, William. "Hamlet." Shakespeare: The Complete Works. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, Inc., (c) 1968. p. 894.

13 Shakespeare, William. "Macbeth." Shakespeare: The Complete Works. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, Inc., (c) 1968. p. 1192.

14 More, Saint Thomas. "Utopia." Machiavelli, More, Luther. Trans. Ralph Robinson. New York: P. F. Collier & Son, (c) 1910. p. 157.

15 Ibid. p. 239.

16 Swift, Jonathan. Gulliver's Travels. New York: Grosset & Dunlap, (c) 1963. p. 129.

17 Ibid. pp. 157-158.

18 Ibid. p. 172.

19 Ibid. p. 188.

20 Ibid. p. 211.

21 Ibid. p. 220.

22 Ibid. p. 235.

23 Boccaccio, Giovanni. "The Genealogy of the Gentile Gods." Trans. Charles G. Osgood. Dramatic Theory and Criticism: Greeks to Grotowski. Ed. Bernard F. Dukore. Orlando: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich College Publishers, (c) 1974. p. 105.

24 Orwell, George. "1984." The Orwell Reader. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Inc., (c) 1956. p. 398.

25 Ibid. p. 410, 412, 417.

26 Orwell, George. "Why I Write." The Orwell Reader. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Inc., (c) 1956. p. 394.

27 Bradbury, Ray. Fahrenheit 451. New York: Ballantine Books, Inc., (c) 1953. p. 28.

28 Ibid. p. 40.

29 Ibid. p. 53.

30 Ibid. p. 136.

31 Tyre, Richard H. "A Note to Teachers and Parents." Fahrenheit 451. New York: Ballantine Books, Inc., (c) 1953. p. 1-2.

32 Huxley, Aldous. "Forward." Brave New World. New York: Bantam Books, (c) 1960. p. xiv.

33 Huxley, Aldous. Brave New World. New York: Bantam Books, (c) 1960. p. 8.

34 Ibid. p. 159-160.

Top

Top

Back to Introduction to Political Fantasy

Back to Introduction to Political Fantasy

Back to Definition of Political Fantasy

Back to Definition of Political Fantasy

On to Defense of Political Fantasy

On to Defense of Political Fantasy

The Christian Guide to Fantasy

The Christian Guide to Fantasy

(c) 3 May, 1999

Updated 13 June, 2000

All Rights Held by the Author.

No part of this document may be used or copied without express permission of the author.